Wilfred J. Barton, Mission December 25, 1944

"Bil" wrote two versions of his experiences. Click here to read the "short" version. The following is the longer, more detailed version.

MERRY CHRISTMAS 1944 AND AFTER

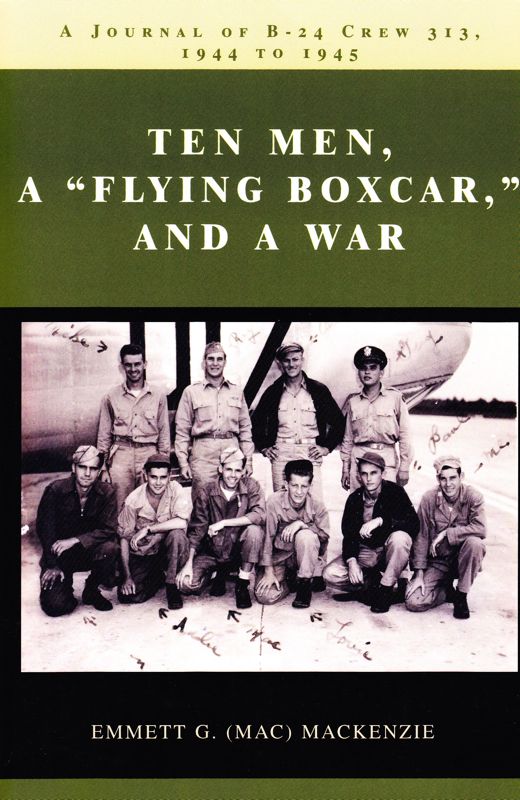

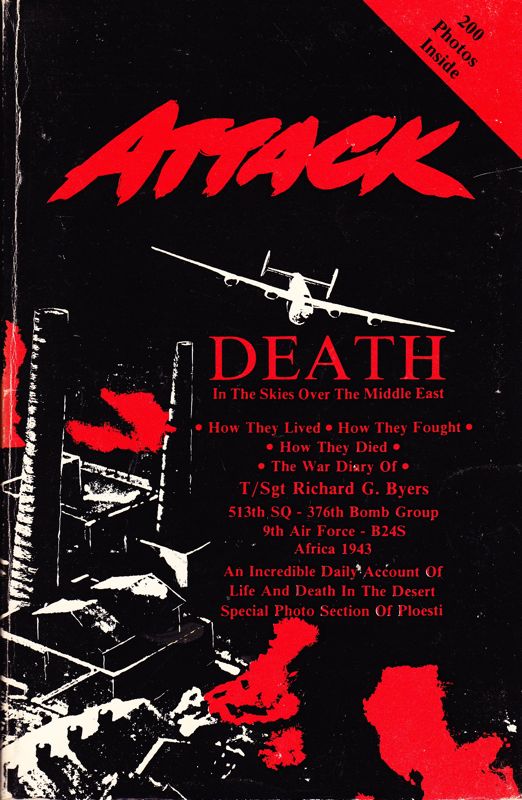

The Army Air Force Jeep rolled slowly through the mud in the early morning darkness. It would stop momentarily then move on again through the area occupied by squad tents of combat crews of the 376th Bomb Group, a part of the 15th Air Force in southern Italy. They were scattered over the slope near the blacktop and metal landing strip. As usual, we would, "sweat it out". We had really hoped to get Christmas Day off. The day before we had gone on leave to Lecci, home of the 98th Bomb Group, and the only town of any size near our base at San Pancrazio. Reluctantly, we had come back early thinking we might be on another mission this morning.

We had made a trip a few days before over Vienna, one of the two worst in Europe; "350 guns bearing on you at the target" according to Intelligence at briefing. We found out they were right as we flew into a solid black cloud of flack on our bomb run. Two of the group didn't come out of it, and we felt pretty fortunate; not a scratch on anyone in our crew even though we counted over 40 holes in our plane after we landed.

The day after the Vienna mission we were over the "Hell Hole of Linz." One ship on our right wing disappeared in a ball of smoke and fire. We always tried to watch for chutes but all I saw was what looked like the Sperry ball turret and a few pieces of sheet metal. They must have taken a direct hit in the bomb bay or caught on fire. B24's had a reputation of blowing up within ten seconds if a fire broke out. On two other days we had hit Salsburg and Rosenheim. That made it four days in a row and, one of the crew said, "I believe they are trying to kill us off."

Then came that Christmas Morning rap on our tent, "Williams crew, everyone out, briefing at 3, breakfast at 4," We rolled out of our bunks and into our heated flying suits, gloves, felt boots, helmets and goggles. The whole unit plugged together and was later plugged into our turret or position. It was going to be another long haul; 8 hours or more at high altitude, 20,000 to 30,000 feet, on oxygen, with the temperature 50 to 60 degrees below zero. All that along with sweating out fighters and flack would see us returning to base exhausted.

We went to get the word: route to target, the 1. P. 's, where to expect flack, weather, etc. They said we were fortunate this morning. It would be a "milk run." We were just going as far north as Innsbruck and hit the Hall Main marshalling railroad yards, "To let those Krauts know there was still a war going on." We hurried on to breakfast, and then went to pick up our chest pack parachutes. Some wise guy had a sign over the counter, "If it don't work, bring it back."

We were soon down to the hard stand checking out a battered and patched B24 with a big 63 on it's side. We checked out our guns, the bomb load, and fuel. We then got our flack suits and helmets into our positions with our chutes nearby. One of the "Ground Grippers" said, "Glad I'm not going with .you guys this morning." When I asked why, he said, "That airplane is wore out!" Charley Johnson of Atlanta, our nose gunner said, "Maybe we will have a White Christmas after all Bart." It wasn't much to look forward to but was quite possible. I had noticed at briefing all the blank spaces where crews were erased on the blackboard due to M.1.A., and had wondered if they would move us up in the line again, or were we to also become a blank space on the board. The number one crew had the most missions and hoped to reach 50 and win a trip back the states.

We finally taxied out onto the runway and took our turn. We had quite a struggle getting airborne and managed it just at the end of the strip. I thought then of another crew that didn’t manage it just before we joined the group. Parts of their ship were still scattered around the area.

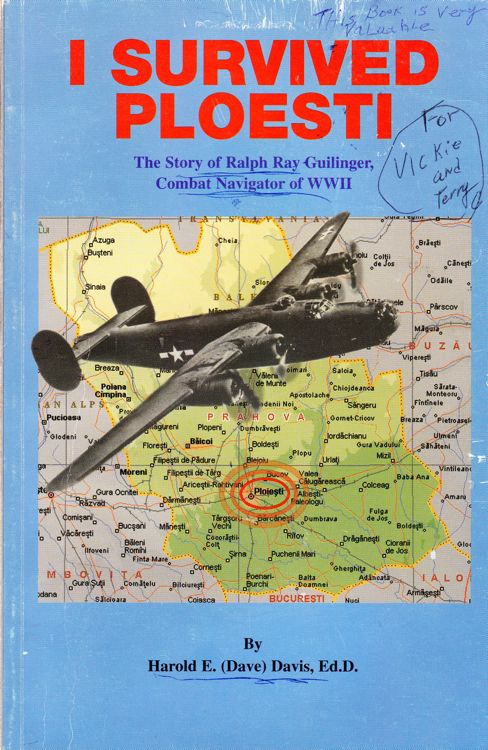

We had a hard time keeping up with the rest of the group. D. D. [Williams], the Pilot said on the intercom that we wouldn't make it back with our fuel load and would probably have to land at Foggia on our return in order to refuel. He also said he was giving it everything he could to keep up. We finally went on oxygen around 12,000 feet, and were soon out over the Adriatic heading north. We could see the mountains of Yugoslavia to the east and later spotted a flight of B- 17's ahead of us heading north also. We flew on by them and then swung inland over the Udine area of Northern Italy. We soon could see the snowy peaks of the Alps of first Italy, then Austria on our right as we headed west and north in the general direction of Innsbruck. We made a number of turns from time to time because we never flew in a direct line to the target. As usual, we picked up light flack, then moderate, then heavy as we approached the target. About that time our luck ran out.

From my position in the top turret I first noticed that our right outboard engine was dead, and the prop feathered with a blade missing. We soon dropped below and behind the formation; another cripple for German fighters. There was nothing to do but try to fight them off as we had no fighter escort. Then there was the high scream of a runaway prop on our right inboard engine. It had to be shut down also and the ship began to slip into a flat spin. About this time I noticed that we were losing the left half of our tail assembly, the horizontal stabilizer was disintegrating, and we were probably on fire. The intercom was out, but I was slapped on my legs from the flight deck below. I saw the co-pilot, Don Mitchell, with his chute on heading for the still open bomb bay.

I checked out also as soon as I could, unhooking electrical, oxygen, and interphone, and snapping on my chest chute. The gravity force was really rough as I crawled back, and the last I saw of Williams he was standing up, fighting the controls, trying to hold the ship steady. He must have followed me pretty fast though, because when I stopped tumbling so I could get my chute open, "Old 63" had already exploded in mid air. Later, as I drifted down, I saw it scattered on the mountain below.

The trip down by chute was extremely quiet with only the occasional soft plop of the small pilot chute on top. Lower down I drifted toward the vertical rock wall of a mountain, and nearly collapsed the chute a couple of times trying to get away from it. There were no other chutes visible and I was worried about Williams. Lower down there was a chalet or house in the timber and deep snow. I landed some distance from it with the only casualty the dye marker we carried in case we had to ditch in the sea. It turned the snow in the area a bright orange.

An old gentleman and two children approached, but stopped at a distance from me until I assured them I had no gun. They came over, and he said ,"kommen, kommen." He and the children then led me to the house. Inside, I was given a chair and then a shot of Schnapps. The lady of the house handed me a bowl of Christmas Cookies, and then had me sit at a table where she gave me a bowl of soup and meat. We tried to converse with an English-German Dictionary, but about then the police arrived from the town below. She hid the left over food under a cot just in time, and as I was going out the door she said, "you Catlic?" I said yes. Her reply was "Dominus Vobiscum.": God be with you.

I stepped out into the snow and saw the two children again. A young German soldier was with them. The guard then directed me on down the slope. Flying boots are lousy skis, but I managed to get down to the lower elevation without falling. There I was taken to another house where co-pilot Don Mitchell was waiting. We found the people there spoke fair English, and were told we might as well give up. They said the war wouldn't last much longer, and that the border to Switzerland was so heavily guarded that it would be impossible to go there.

We were then taken further on down the slope to the town where we were put in a cell in the local jail. We were later visited there by another guard who needed my gloves, and in spite of an argument, walked out with them while I got up off of the floor. The cell was unheated and during the night I held Mitchell's feet between my legs to keep them from freezing. He had lost his flying boots and was wearing his G.1. shoes that he had tied to his chute harness. I had lost my shoes with the delayed chute opening.

We left Rottenburg, and went on by train toward Southern Germany. We were stopped in route for interrogation. I gave the interrogator my name, rank, and serial number, as required, but he insisted that I give him the name of our bomb group or I would be shot as a spy. He also asked for our tail markings which I also refused. I then asked if he would answer those questions if he were in my place. This ended it. His parting remark was, "The reason you people are winning this war is because you are so damn confused we can't figure out what you are going to do next." I agreed with him.

Our next stop was a German Air Base near Aibling. We all managed to get there together except for Cliff Faith of Cincinnati. He came in last, and looked as though he felt pretty low. We saw him first and said, "Hi Cliff'. Boy, what a change! He said he had been told we all went down with the ship. He had seen it explode after he bailed out, and thought the worst. While at Aibling some German pilots visited us, they were friendly and one said Roosevelt could stick the whole R.A.F. in one pocket. They said our P-38's were bad news but that they didn't stand a chance against our p-51's. They took off fast when a guard came. We were finally given some food, a slice of rye bread, which we tried on some birds outside our cell. They wouldn't touch it, but we later wished many times that we had kept it.

We finally boarded another train and headed north. In one town air raid sirens cut loose and we had to get out and run. Two of us carried the bombardier who had broken his ankle. We looked, and here came a single P-51, low, down the tracks spraying bullets. Then he pulled up and dumped a bomb on the station we had just left, thus delaying our journey on north. Finally under way we saw a lot of "window" hanging in the trees: aluminum foil air crews dropped to confuse the radar of anti-aircraft guns. We also saw the destruction of the cities along the route. Often, especially in Frankfurt there were areas where there was only rubble with an occasional standing wall section. It was impossible to tell where the streets were. We finally boarded another train and headed north. In one town air raid sirens cut loose and we had to get out and run. Two of us carried the bombardier who had broken his ankle. We looked, and here came a single P-51, low, down the tracks spraying bullets. Then he pulled up and dumped a bomb on the station we had just left, thus delaying our journey on north. Finally under way we saw a lot of "window" hanging in the trees: aluminum foil air crews dropped to confuse the radar of anti-aircraft guns. We also saw the destruction of the cities along the route. Often, especially in Frankfurt there were areas where there was only rubble with an occasional standing wall section. It was impossible to tell where the streets were.

Eventually we arrived at a large distribution area, Dulag Luft. There were a lot of POW's there. Some were in sad shape particularly a number of burn victims with noses, and ears, burned off. We met a crew from the 98th Bomb Group there, and they wanted to know what took us so long. Their Pilot Williams and our Pilot Williams had gone through Cadets together. We spent a few days there and were told what to expect. One day we watched a flight of P- 47's dive bomb and strafe a German train a couple of miles from the camp. It burned and blew up all afternoon. At first we started to cheer but the Colonel in charge yelled, "Keep your damned mouths shut, the guards just might open up on you!" This particular Colonel had been flying a "Jug" (P-47) and got so low strafing a German air base he curled his prop tips on their runway.

The enlisted men of our crew were sent back down to Stalag Luft #17, at Nuremburg, and were put in unheated barracks. We slept on the floor and wore anything we could add to try and keep warm. It was our longest stay in one camp. We had temporary visitors at one time: Infantry that were captured at the Battle of the Bulge. They separated Air Crews and Infantry most of the time and we believed they liked us the least.

At Stalag Luft #17, We were on a slow starvation diet; a small portion of soup twice a day, and a slice of sour rye bread. We called the soup, "Green Death". It was made of cabbage leaves with no salt, and usually had small white worms in it. Sometimes on Sunday, we got Pea Soup with Beetles. Our daily intake was under 900 calories: not enough to sustain human life, so we were told. Most of us had dysentery and became pretty weak. My thighs shrunk down to become smaller than my knees. Sleeping at night was rough. In any position your bones seemed to cut through your skin.

Eventually we arrived at a large distribution area, Dulag Luft. There were a lot of POW's there. Some were in sad shape particularly a number of burn victims with noses, and ears, burned off. We met a crew from the 98th Bomb Group there, and they wanted to know what took us so long. Their Pilot Williams and our Pilot Williams had gone through Cadets together. We spent a few days there and were told what to expect. One day we watched a flight of P- 47's dive bomb and strafe a German train a couple of miles from the camp. It burned and blew up all afternoon. At first we started to cheer but the Colonel in charge yelled, "Keep your damned mouths shut, the guards just might open up on you!" This particular Colonel had been flying a "Jug" (P-47) and got so low strafing a German air base he curled his prop tips on their runway.

A big day came! We finally got some Red Cross Food Parcels. I had 17 men in my group to divide the parcel with. I had to walk a block to get it. Then I had to get help to carry it back, even though it weighed only 5 or 10 pounds. The most valuable thing in the parcels was the one pound box of raisins. We counted them and put them into equal piles. I made my share last a week. I ate one at a time, only a few each day, and chewed them as long as possible. There was also a one pound box of powdered milk and cigarettes. The cigarettes were green with mold, but we smoked them anyway.

We added to our diet by drinking warm water heated by slivers of wood and pieces of grass in a tin can sitting on three rocks. We also ate pieces of grass when they came up. One day there was a bomb raid on Nuremburg: 24's and 17's. We saw some coming down in flames and watched for parachutes. We had to stay inside because so much flack was coming down from above. One Airman parachuted into our compound. After the raid our soup improved. They brought in bones of a horse. The recipe included everything, even the hooves and the hair around them.

The slivers we used to heat our "Kriege Brew" (water) were usually from a board ripped off the "Wash House" at night and tossed through a window. The guards would come in on the run, but when they arrived we would all be laying around talking; the board already in splinters and hidden.

Every morning we had "Appel": roll call. It was, "Raus mit! los! los!" We would line up in rows five deep and they would start counting. The guys in back would change places and when they got to their row they would raise H- and start over. We would say to each other, "Them Krauts can't even count." Then we would do it again. It would often take an hour or more and we would get pretty cold.

Inside the barbed wire entanglements around the compound at six feet was a single strand of wire. If you touched it they would shoot you. We used to walk near it, and stare at the guard. When he stopped, we would stop. We wouldn't say a single word, but the guard would have plenty of words for us. He was always unhappy about it.

We had Australians, Canadians, and English flying personnel in our compound with Russians next to us. We got alone good with them too, and it was always, "Hi Comrade!" We heard they would take their "Stiffs," (dead bodies) out to roll call so they could be counted, and they could get extra rations. I tunneled under the entanglements into their area one night between search light sweeps. I didn't accomplish anything but one guy gave me an inlaid cigarette holder which I kept for years.

The war progressed and we had to leave Nuremburg. Those too weak to walk were going by train. I decided to walk. Too many men in our compound who couldn't make it out to morning roll call in the past were carried out of our compound, and we never saw them again. We also had seen what was happening to German trains, and understood as well a good reason for our short rations. We had their transportation crippled. Over 1,000 locomotives were destroyed by the 15th Air Force fighters in one year along with freight cars, trucks, etc.

We headed south slowly. Some had blankets, and we would pair up and try to keep warmer at night. If they were available we slept on branches to keep off the damp ground. On occasions, when we heard planes coming we used anything we could find to spell out POW. It was a long walk but we finally arrived in Moosburg. It was very crowded there, and I read afterward that there were over 25,000 prisoners from several of the Allied countries.

The first night after arrival, I heard a board rip off the latrine, so I hurried out to get my share. The next morning there was only a foundation and the guards were walking around shaking their heads. I heard one say “Der shisen haus is kaput!"

I had teamed with Gene Brillhart of Perryton, Texas. He had been in the 9th Air Force and was the only survivor of his crew. The others were shot coming down in their chutes. He landed safely and survived by hiding under some brush for four days until a German military detachment came by. One day, shortly before we were liberated, we were making a Kriege Brew with a small can of water. Bullets and even shells were coming pretty close. Others yelled at us to take cover. Gene finally looked up bleary eyed and said, "They gettin kind of close ain't they George." We couldn't stand the idea of giving up our portion of the Kreige Brew so neither of us moved.

Then, on the last day of April, the 3rd. Armored Division arrived. A tank knocked down some of the barbed wire and the guards threw down their guns. They said, "Deutchland is Kaput!" We thought at last we would get some food. An officer got up on the roof of one of the buildings and said we would all be on our way home in one to two weeks, either by air or hospital ship. He was sadly misinformed. A couple of days after that I picked up a piece of orange peel out of the mud and ate it.

In a week we left for a German Air Base where some C-47's flew us to Rheims France. We were there for a week or so, and then went to Camp Lucky Strike on the Northern French Coast. Every day we lined up for egg nog. It may have been good, but the thick white coating on my tongue made everything tasteless.

Days and weeks went by, we were told the War was still on with Japan ! ! !, and to just, "be patient." One airman from the 8th Air Force, Homer Miller from Iowa talked me into hitchhiking a ride to England on a B-17 mail plane so he could check on his old outfit. We had some money from the Red Cross at Lucky Strike so we took off. We found his old Bomb Group, and got a couple of escape maps for souvenirs. I still have mine. We took a quick trip to Edinburg, Scotland before returning to London. We also visited an Ex-POW British pilot named Ronnie Streatfield, in Kent. On our return again to London, we met a sailor from Millers home town. We asked if he was going back to the States soon. He said, "Sure!" He said to come up to Northampton in a couple of days and he would get us on board his ship.

We were there in plenty of time, but Miller's friend hadn't told us his ship was an LST! It started rolling the minute it pulled away from the dock, and was very slow. It's top speed I was told was four knots. One time in the Atlantic, in a rough sea I asked a sailor how fast we were going. He said, "Right now we are losing ground." It took 27 days to get to Newport News, Virginia.

The Navy was good to us though, and they kept their ship spotless. They were even painting and chipping paint on calm days. One big problem we had for the whole trip was holding our mess kit with one hand so it wouldn't slide off on the floor, while we ate with the other hand. We were able to pay them back for their good treatment one night when the Injectors on the Diesel engine went on the Fritz. My Ex-POW airman Mend, Homer, was a Diesel Mechanic back in Iowa before the War. He overhauled the injectors and had the engine going by morning.

The Army at Newport News wanted to know who we were. We said we were "RAMPS": Recovered Allied Military Prisoners. They then wanted to see our paper work. We had none, but they fixed us up with leave papers after filling out some affidavits. We caught a bus out from Newport News, and I was able to hitch hike the last 200 miles from Omaha after arriving there.

Nebraska hadn't changed much, and was very different from Germany, which by the way must have once been a beautiful country. It probably is again today. I hope so.

"Bill" Barton

Authored some time around 1968 at Lancaster, CA

Submitted by Lloyd A. Marshall- good friend and neighbor to "Bill" Barton

The website 376bg.org is NOT our site nor is it our endowment fund.

At the 2017 reunion, the board approved the donation of our archives to the Briscoe Center for American History, located on the University of Texas - Austin campus.

Also, the board approved a $5,000 donation to add to Ed Clendenin's $20,000 donation in the memory of his father. Together, these funds begin an endowment for the preservation of the 376 archives.

Donate directly to the 376 Endowment

To read about other endowment donation options, click here.

Reunion

NOTE change in the schedule !!

DATES: Sep 25-28, 2025

CITY:Rapid City, SD

HOTEL: Best Western Ramkota Conference Hotel; 2111 North LaCrosse St., Rapid City, SD 57702; 605-343-8500

Click here to read about the reunion details.