Dave Burton mission February 23, 1944

OUR LOVE AFFAIR WITH PRATT & WHITNEY MISSION

-MESSERSCHMITT FACTORY, REGENSBURG, GERMANY (Published 1991)

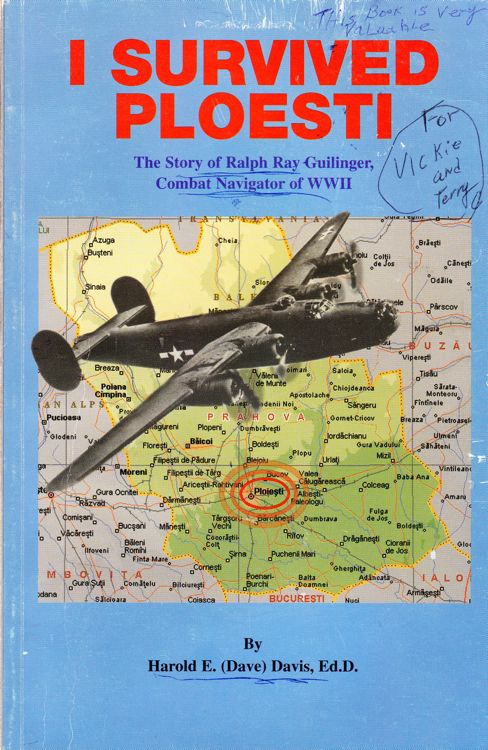

There are many stories about the Pratt & Whitney engines and their ability to bring a four-engine B-24 back on three engines but only a few crews can talk about coming back more than 600 miles on two engines. This is a true story of one of fifty missions my aircrew flew in a B-24 over Southern and Central Europe and the Balkan States, including the Ploeste Oil Fields.

On this day, Wednesday, February 23,1944, the crew members were awaken by the Squadron Orderly at 4:00 AM, had a breakfast of stale toast, scalding strong coffee along with dried eggs made into rubber and we hopped aboard the briefing truck when it came by at 5:15 AM. The Briefing Room was filled with nervous laughter, cigarette smoke and loud coughing as the flying officers milled around waiting for the start of the briefing.

A voice yells, "Gentlemen, take your seats," and there is a rush and shuffle to find a seat next to a buddy or crewmember. Another command, 'Ten-shunt," and we jumped to our feet as the Group Commander strides across the stage. Pulling back a drapery on the wall, he disclosed a large red ribbon strung across the wall map indicating we had a long eight or nine hour mission ahead of us.

Take off was scheduled for 6:30 AM.

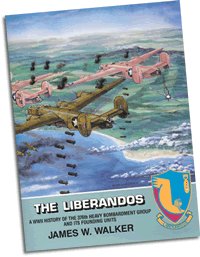

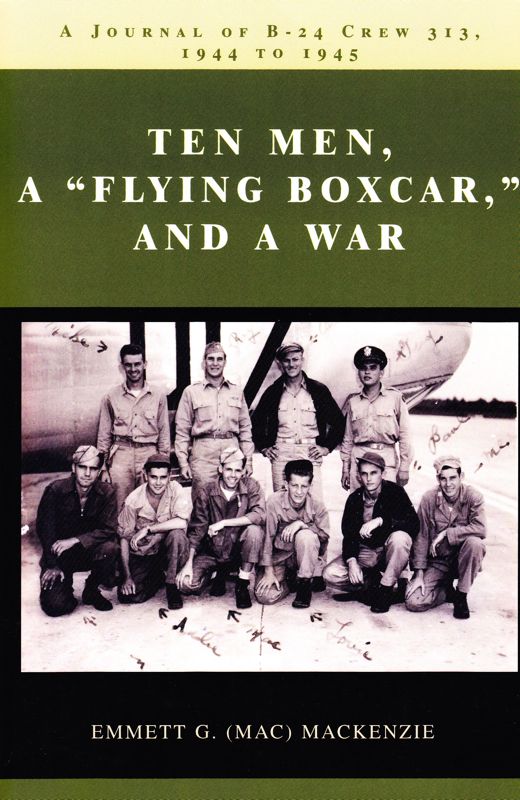

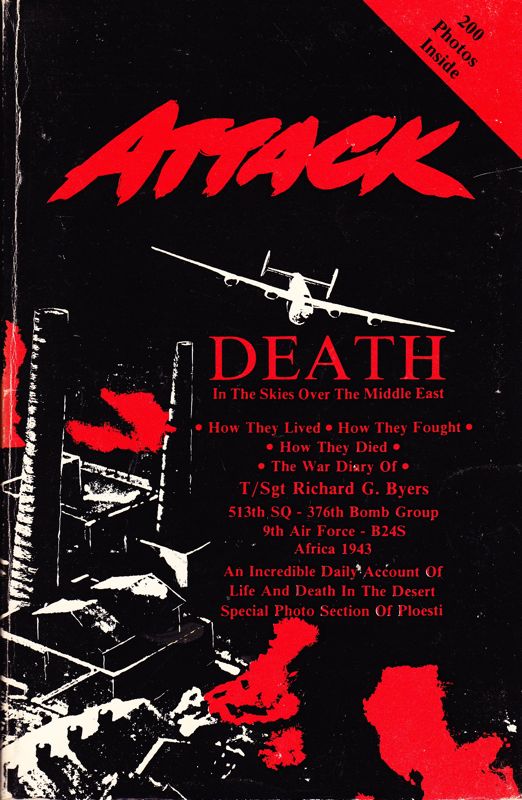

My crew consisted of three other commissioned officers and six non-commissioned officers. They are: Co-pilot Lt. Milt Shuman; Navigator Lt. Hugh Banta; Bombardier Lt. Dan Delaney, Engineer Sgt. Ed Steiner; Asst. Engineer Sgt. John Knol, Gunner, Sgt. AI Kurzonkowski; Nose Gunner Sgt. Harold (Bill) Furney; Tail Gunner Sgt. Bob Mellinger and Radio Operator Sgt. Herb Graham. We were attached to the 512th Squadron, 376th Bomb Group, 47th Wing of the 15th Air Force flying out of San Pancrazio, located on the "heel of the boot" of Italy.

This was my crew's seventh combat mission and our Group of four squadrons put up about 50 planes for this mission. We were joined by about 150 other B-24's that were carrying thousands of high explosive and incendiary bombs to one of the main factories of the ME 109 fighter aircraft in Regensburg, Germany. Bomber crews appreciated this kind of strategic mission because; instead of railyards or oil refineries we could deal directly with the enemy fighter we knew and fought.

The Germans protected these aircraft factories with everything they had at their disposal. Dozens of fighters attacked the bombers going to the target and also attacked them after the ground anti-aircraft shells had taken their toll and crippled some of the bombers.

We were on the bomb-run when shrapnel hit our No.3 engine from an anti-aircraft shell that exploded near the co-pilot's side of the plane. I pushed on more power to the remaining three engines in order to stay with the formation on the bomb run.

A bomber with one engine feathered and lagging behind the formation always attracted enemy fighters because a bomber that was already crippled is easier to shoot down. Our three engines responded but then I noticed the No.1 engine's oil pressure was dropping and the RPM was fluctuating. By the time we released our bombs and were headed for home base, No.1 's prop governor was failing and the prop started to "runaway" or overspeed. It had to be feathered before the engine froze-up and it couldn't be feathered.

It was now decision making time. If we kept flying, we could not keep up with the formation and would lose the protection of the other plane's gunners. We were also losing altitude and expected to become an easy target for the enemy fighters. On the other hand, if we bailed-out into the enemy-held snow covered mountains below, we might not survive anyway.

Another option was to throw out everything that was loose in the plane, including guns and ammunition and stay with the plane until it was going to crash or was being shot down by enemy fighters. This last option was the one selected and we set about making the last two Pratt and Whitneys take us as far as they could before they failed. We felt that every minute we could keep flying brought us about three miles closer to home and would save us at least a day of hiking on the frozen earth below.

Lady Luck was with us because by the time we could no longer stay close to the formation, the enemy fighters had left the area. It was now time to concentrate on how to keep our B-24J in the air as long as possible.

The two 1,200 horsepower, R-1830 Pratt and Whitney engines were now being "sacrificed" for the few minutes of flying time we thought we could expect from them. Normally, the allowable take-off throttle settings of 49 inches manifold pressure and 2700 rpms were to be used for only a maximum of 5 minutes. To keep from losing too much altitude and flying speed, we turned up the supercharger past these settings and when the engines would get too hot, we would cut back on the power and let them cool off. We wondered how long these engines could take this abuse.

At normal settings we lost altitude and even though we started at 23,000 feet, a decent of 200 to 300 feet per minute meant we would be out of sky before we could reach the Adriatic Sea where the Air-Sea Rescue Units waited. Switzerland was another option but we would be interned for the remainder of the war. The entire crew wanted to try to get back to home base.

Over the next couple of hour~ the engines responded every time we applied full power to them. The plane was becoming lighter because of the large amount of fuel we were burning so we were still at about 6,000 feet altitude by the time we reached the Adriatic Coast. We radioed Air-Sea Rescue because we knew if one engine quit, we would ditch the plane in the sea and hope they would pick us up.

Everyone of the crew was up on the flight deck watching the engines and instruments, especially the altimeter and rate of decent. It appeared that we were almost holding our own. If the engines held up to this tremendously high manifold pressure and rpms, for another two hours, we would make it home.

I yelled over the sound of the engines, "We're approaching an Air-Sea Rescue boat so now is the time to decide if you want to bail-out. They say the sea is not very rough and they shouldn't have any trouble picking you up. Since you'll have to jump from this altitude, you might land some distance from the boat. We can't afford to lose the altitude we have. Does anyone want to go?"

There was a lot of yelling and laughing and wisecracks about who could swim or who was the heaviest or the most expendable, but the general consensus was, "Hell no, we stay with the plane and crew and trust that those two beautiful Pratt and Whitneys keep running."

Those engines were treated with tender loving care, if it can be said that running them at higher than take-off power settings was TLC. They ran too hot all of the time and the high oil temperature and low oil pressure told us we could lose either engine at any time. We knew our safety depended on both engines continuing to run because some lives would be lost if we had to ditch in the sea. Even when we passed anotherAir-Sea Rescue boat, the crew wanted to stay with the plane and ditch if we had to.

Later, as we passed over the Eastern Shore of Southern Italy, we had a number of opportunities to land at other airbases. They looked good to us, but there is a masculine pride that comes over men at times like this, "We've come this far and the engines are still working, let's go for it!"

Since there is no radio contact with the tower at our base and we knew that we didn't have the luxury of making more than one approach, we flew over the base at about 1,500 feet, firing red flares and hoping they would see that we had two engines feathered.

The tower did recognize our plight who in turn fired red flares, telling other planes to get out of the landing pattern and let us in. We had to crank down our landing gear and flaps by hand because we had lost our hydraulic pressure when the No.3 engine was hit.

Many times in practice, we would bet among ourselves that I would not have to touch the throttles after I cut the engines in the landing pattern. It was a game of flying to a certain point on the downwind leg, cutting off all the engines on the B-24 and coming in "Dead Stick". On this mission, it was no game. I was afraid that if I used the normal approach pattern, these tired engines would quit when I pulled back on the throttle and we would hit short of the runway.

Bob Mellinger continued to fire red flares, letting other ships know we were in trouble and I pulled back the throttles as we turned on the base leg. All the crew took crash-landing positions, in case we came in short. With half flaps, the B-24 glided just as other planes had done and as we turned onto the final approach; I called, "Full flaps we've got it made! Thank God for Pratt and Whitney!" Everyone let out a "Yah-hoo" when the landing gear settled on the runway.

Our ground Crew Chief couldn't believe what we did to those engines and how we still kept flying. It was the last flying those engines did. They were so hot when we shut them down that some of the parts literally melted.

That night, as we sat around bragging about our mission, we paused and toasted, "Here's to Pratt and Whitney and those wonderful men and women in their factories that make those magnificent engines. Hear! Hear!"

The website 376bg.org is NOT our site nor is it our endowment fund.

At the 2017 reunion, the board approved the donation of our archives to the Briscoe Center for American History, located on the University of Texas - Austin campus.

Also, the board approved a $5,000 donation to add to Ed Clendenin's $20,000 donation in the memory of his father. Together, these funds begin an endowment for the preservation of the 376 archives.

Donate directly to the 376 Endowment

To read about other endowment donation options, click here.

Reunion

NOTE change in the schedule !!

DATES: Sep 25-28, 2025

CITY:Rapid City, SD

HOTEL: Best Western Ramkota Conference Hotel; 2111 North LaCrosse St., Rapid City, SD 57702; 605-343-8500

Click here to read about the reunion details.