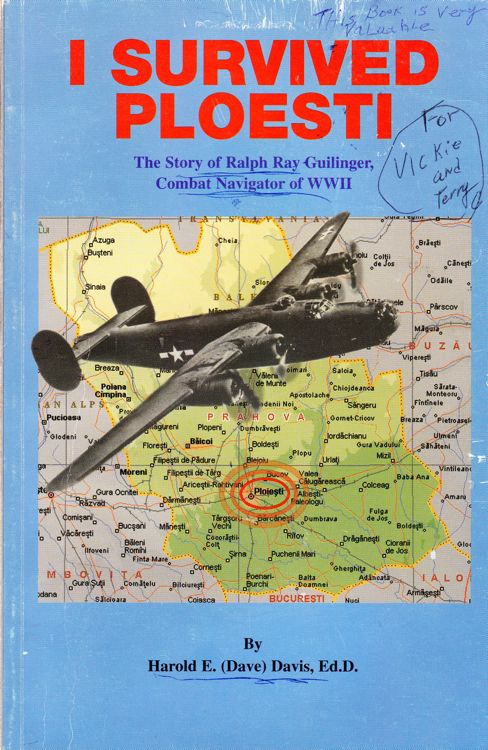

Dave Burton mission April 12, 1944

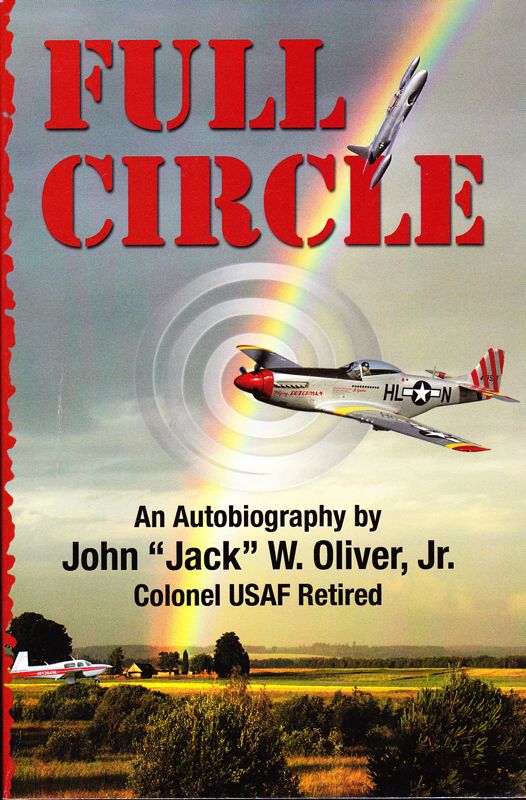

FLYING WITH THE LAST OF THE ROYAL YUGOSLAVIAN AIR FORCE

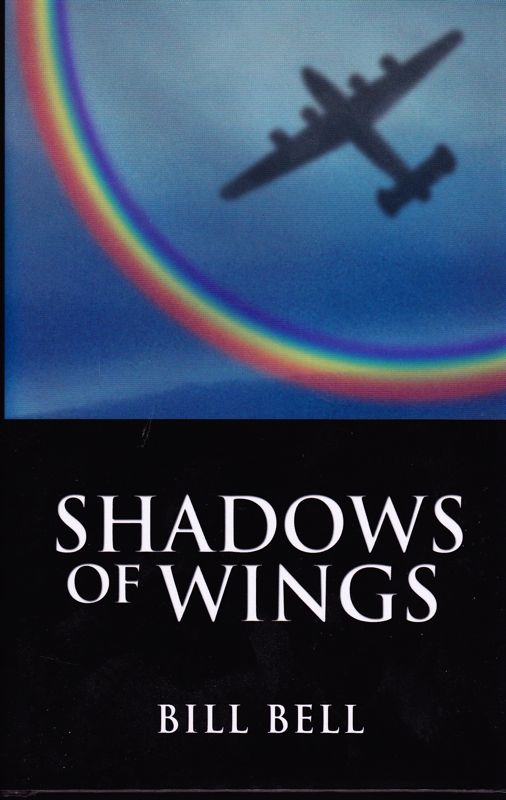

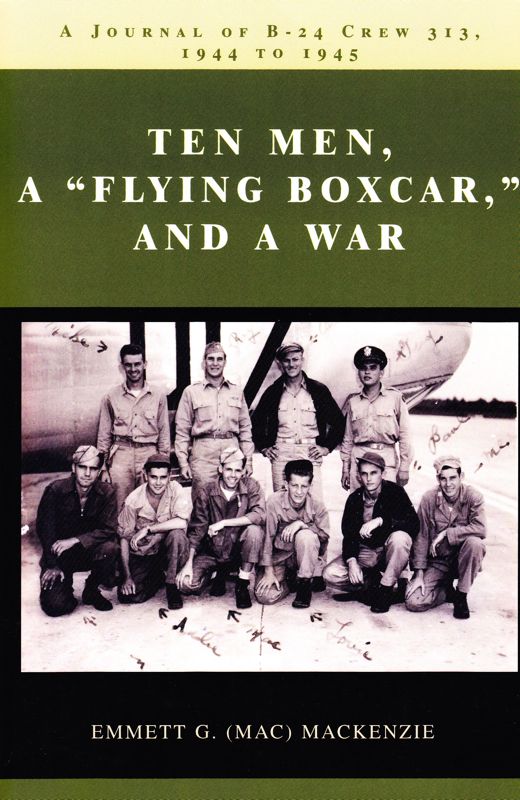

After Germany invaded Yugoslavia in World War II, some members of the Royal Yugoslavian Air Force managed to escape from their country. These pilots, navigators, bombardiers and gunners of various ranks, were sent to the United States to be trained in a 4-engined bomber called the B-24 Liberator. There were ten men needed on each bomber crew and the 40 airmen each took positions regardless of their individual rank.

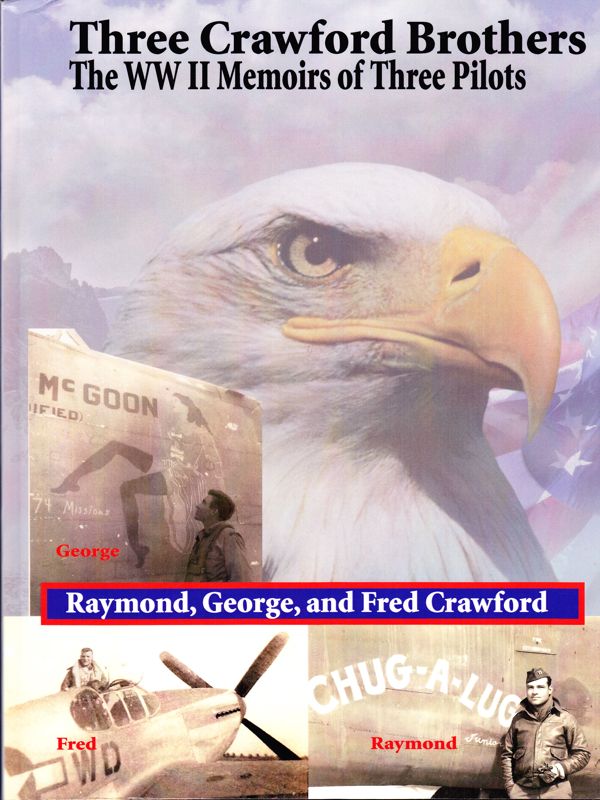

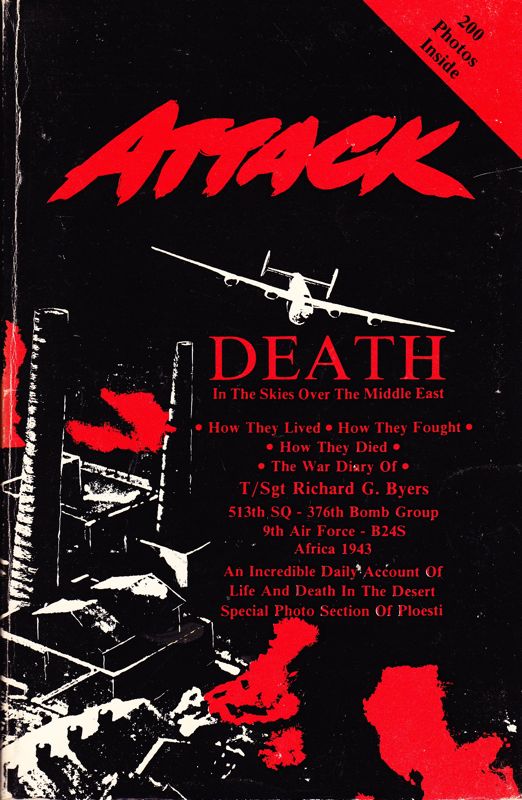

After their training was completed, President Roosevelt presented the aircrews with four B-24's. In October 1943, the Yugoslavian crews were ordered to fly their planes to Tunisia, Africa and join the 512th Squadron of the 376th Heavy Bomb Group.

By December 1943, the 376th Group had moved to San Pancrazio, a former British Fighter Airbase located near Taranto at the "Heel of the boot" in Italy. During the next few months, the Yugoslavians flew bombing missions into the heart of Germany and the Balkan States.

There were no allied fighter escorts capable of making these long missions to protect the bombers and the 376th Bomb Group suffered heavy losses to enemy fighters. Antiaircraft batteries were concentrated around these important military and industrial complexes and many bombers fell to radar controlled flak barrages. Two of the four Yugoslavian aircrews were lost during this period.

In April of 1944 one of the two remaining Yugoslavian aircrews with Captain Voya Skakich as pilot was flying in the Group Formation I was leading into Wiener Neustadt, Austria. Our Group was assigned to bomb the Messerschmitt aircraft factory and airfield with incendiaries and 500 pound demolition bombs. Some of the bombs had delayed action fuses to keep the German firefighters at bay.

Going into the target area, our formation was being agressively attacked and taking a beating from fighters flying head-on straight through our formation, their 20mm cannon and machine guns blazing at us. More enemy fighters attacked us in groups of six or eight from low and behind. Our bomber group's twin 50 caliber machine guns were answering with thousands of bullets chasing the illusive fighters as they zipped in and out of our formation.

"Damn! A 20mm just exploded in my turret!" yelled tailgunner Sgt. Bob Mellinger over the intercom. Mellinger was not a guy subject to hysteria and I asked waist gunner John Knoll to check on him.

"I'm OK," came the immediate response, "but it sure'n hell scared the crap out of me."

"You'll have to clean up your own mess, Bob," came an unidentified voice.

"Hey, left waist and ball, get those bandits coming in low at 9 o'clock, I can't depress my guns low enough to get them," top-turret gunner Sgt. Herb Graham called on the intercom. Sgt. John Knoll in the left waist window and Sgt. AI Kurzonkowski in the ball turret responded immediately, sending tracer lit bullets toward the oncoming fighters as they made their deadly "fighter curve" attack.

"We got one! We got one! Did you see that! That son-of-a-bitch exploded right in my face!" Knoll yelled into his throat mike.

"Nice going, John and AI! Did anybody else see that? Co-pilot Lt. Milt Shuman asked.

"Steiner to co-pilot. Yeah, I saw the pieces come by my side of the plane. Hell, he almost rammed us! Great shooting!"

"Oh Shit!" shouted Sgt. Bill Furney in the nose turret.

"There goes another '24 on fire! Come on you guys, get out! Get out! There's one,.there's two,.four chutes. Oh damn! There she blows! No more chutes! That was a green 24-J. Six airmen lost! Four parachuted! I wonder who made it?"

There was silence on the intercom for a moment as some of us thought about the ones lost and how close we came to getting hit but the attacking fighters soon brought us back to the battle at hand. There was no time to worry about our lost buddies. We would mourn them later.

The silence was broken immediately and the intercom came alive again with the voices of the crew, calling out attacking fighters, asking for verification of a fighter they shot down or naming a bomber in trouble.

Finally we approached the Initial Point (start of the bombrun) and the enemy fighters broke off their attack with one last pass vertically down through the formation. This signaled their antiaircraft batteries to open up. Puffs of black smoke with bright orange centers started to fill the sky ahead of us .

. By the numbers of antiaircraft shells exploding nearby, we guessed there were about 200 guns aiming at us. As we flew into the flak cloud of black smoke we could hear the shells exploding, smell the acrid smoke and feel and hear the shrapnel hitting the plane. Every crewmember checked to make sure his flak jacket was on tight around his body and 'family jewels'.

We all adjusted our steel helmets. There was a joke around the flight crews that said, "He was so scared, the only thing sticking out of his steel helmet was his feet."

I held the plane steady and straight as the Bombardier lined up his bombsight and I kept the Pilot Directional Indicator (PDI) on zero. "PDI centered" I called to the Bombardier, Lt. Dan Delaney,

"Auto Pilot engaged!"

Now the plane responded to each movement of the bombsight as Delaney lined up on the center of the target area. As Lead Bombardier of the Group, the failure or success of the mission depended on his skill to guide the plane to the target using the automatic pilot controls connected to the bombsight. All of the other planes in the formation would be dropping their bombs immediately when their Bombardier saw the bombs leaving our bombay. Our Group of36 bombers drew into a close formation so our bomb pattern would be concentrated on the target below.

"Bombs away" Delaney called on the intercom.

"Bombs away confirmed" replied Flight Engineer Sgt. Ed Steiner, as he checked the open bombbay.

As we started a slow left turn off the target, I used the command radio to ask the other pilots in the Group, "Red Leader here, I'm slowing down to 150 indicated airspeed because we have some feathered props out there. Anybody not going to make it?"

An excited, heavily accented voice came back over the radio, "Skakich to Red Leader, we're hit bad, one man is dead, another two or three badly wounded and our.plane is in bad shape! One engine gone and flight controls hit, I can't steer the plane! Fighters are attacking us; it looks like we'll have to bail out. Goodbye!" It was Captain Skakich, the pilot of one of the remaining Royal Yugoslavian Air Force crews.

Captain Skakich was an experienced airline pilot before the war and knew his airplanes. He was a great storyteller and kept us entertained with hair-raising stories about flying patched up airplanes to remote airports around Europe. There was no doubt about his flying ability but could he fly this wrecked B-24 over 600 miles after it had lost its flight controls, was flying on three engines and being attacked by enemy fighters?

"Roger, Skakich, Red Leader here. Standby! Don't bail out yet! Try to get your autopilot working and I'll try to keep the fighters off you," I responded.

I switched to intercom, "Pilot to Tail, can you see the Yugo plane? Should be a desert pink B-24 J and in a slight bank away from the formation, one engine feathered.

"Roger, Skipper," Tailgunner Mellinger answered. "I see it. It's 4 o'clock low about 500 yards out. A couple of fighters are attacking them! They are really getting hit!"

"Do you see any smoke?" I asked.

"Nothing bad, Skipper, just some white smoke off the feathered engine. Probably just some oil leaking on the hot engine. Should be OK."

"Roger, Tail, I'm going to try to cover them with our formation to keep the fighters off until they can get control of the plane and try to set up the auto-pilot but I'll need your help in guiding our formation over to them. Switch your frequency to command radio. Let me know if we get too close.

Engineer Sgt. Ed Steiner interrupted on the intercom, "Four bandits circling us at 10 o'clock high, about 1,200 yards."

Co-pilot Shuman responded, "OK Steiner, keep an eye on them and give them a short burst, if they get closer.

Listen gang, I'm going on command radio and try to help get those Yugos home, if they can get their autopilot working. Shuman, tap me if I'm needed on intercom."

I switched to Command radio and announced, "All pilots in Group three, Red Leader here. We are going to try to surround the Yugo plane, now at 4 o'clock low so we can keep the fighters off them. They are trying to set up the autopilot. Do not fly too close to him when he engages the autopilot because it may be damaged and cause their plane to make an erratic maneuver.

"Red Leader to Skakich, we are moving the formation over to cover you now. Try to keep the plane as steady as possible. Have you tried the autopilot yet?"

We've engaged it and are getting it adjusted, seems OK." came the reply.

The fighters broke off their attack early because they were being hit by some of our Group's gunfire. They circled for one more half-hearted pass from 5 o'clock low. It is possible they recognized our attempt to rescue one of our own crippled planes and respected the effort by not pressing their attacks.

The Group turned West and the change in direction put the formation on a heading of 270 degrees and away from the homebound course.

"Skakich, this is Red Leader. We have you pretty well surrounded so if you can, let's take up a 1850 heading for home."

"Tail to Pilot, they're coming around Skipper. Starting a slow turn to the left."

"Roger, let me know if they make any fast moves."

The planes of the formation opened up around the Yugo plane and it passed beneath the lead squadron until it was visible out of my side window.

"OK Tail, I've got them now. Thanks for the help."

"Skakitch, I can see you now. Is the autopilot working O.K.?

"Roger. Autopilot is OK," Captain Skakich responded.

"Now don't make any fast moves, we have to follow you and we can't make this formation move fast." I cautioned.

The enemy fighters still circled at a distance like a pack of wolves waiting for a crippled plane to drop out of formation. They could see we had a number of planes in trouble.

Captain Skakich was able to keep the plane in a reasonably straight flight and the formation was maintaining their positions around the crippled ship and other bombers with feathered engines were having no trouble staying with the formation because of our slower speed.

I broke the silence with, "How are the wounded in your plane, Skakich?"

"One is very bad, we can't tell if he is alive or dead." was the Captain's sad response.

"Sorry, Skakich, but let's get them home."

Everyone in the Group was feeling better now because we could tighten up the formation and discourage any last minute fighter attacks before we reached the Adriatic Sea. The enemy did not venture over these waters because the American and British Air/Sea Rescue ruled that sea and if an enemy plane was shot down, they would drown or be captured.

Once over the Adriatic, Yugoslavia was only a few miles off our left wing and the thought occurred to me that the Yugoslavians could find a haven there if they flew over there and bailed out now.

"Skakich, Burton here, would you and your crew want to bail out over Yugoslavia? You might lose another engine or the Autopilot could go out and you would crash in the Adriatic or you may crash when you try to land. I don't know if you can land a B-24 safely on autopilot."

At this time in the war, there was a lot of fighting in Yugoslavia. The Royal Chetnicks and the Communist Partisans were fighting a Civil War. At the same time, they were both fighting the Germans who had invaded their country. However, as American flyers, we were informed of certain "safe areas" controlled by the Yugoslavian forces and if an American came down in either territory, the Yugoslavians would call a truce in order to escort the Americans across their front lines and out of the country. Many times one of our planes would be forced down over or near Yugoslavia and the plane's crew would show up at home base in a couple of weeks.

The rescued Americans said it was hard to keep up with the Yugoslavian rescue parties because they hiked fast and long, ate little more than a soup or broth and stopped for nothing, including broken bones, sore feet and aching muscles.

Captain Skakich spoke in a slow, thoughtful tone, "No, we don't dare try to drop into Yugoslavia. Ifwe landed where the Germans or the Communist Partisans are in control, we would be shot.

Remember! We are with the Royal Chetnicks and I can't be sure what land they control. Besides, with our wounded, they would probably die from exposure in the frozen forest covered mountains below. We all want to go to our Home Base. We have been lucky so far and we believe it will hold."

Our formation followed the coast South for nearly two hours and made the turn West to the eastern coast of Italy. As we approached the Italian coast, I called our Deputy Leader flying on my right wing, "Red Leader to Deputy, take the Group on to the Base. I'm going to stick with the Yugos and try to help them land the plane on autopilot. We'll give you enough time to land your planes and clear the runway. Tell Base Operations when you get down, we will be making a long final approach from the South and they will be coming in with power on, both high and fast. They may not be able to stop in time. Ask them to have crash and meat wagons at the end of the runway.

"Roger, wilco and good luck to Skakich," came the response.

The formation flew away to the Base and I stayed with Captain Skakich's plane. It then occurred to me that I was flying with one of the last of two Royal Yugoslavian Air Force crews left in the world and I realized they had historical significance to the Allied War effort, an exhilarating but sobering thought.

"Burton to Skakich, take your time testing how your plane reacts when you drop flaps and wheels and cut the throttles. We still have enough altitude for anyone of your crew to bail out if they want to. My Navigator, Hugh Banta, will mark the spot and we'll have a jeep pick them up right away. No use all of them taking a chance on a crash landing."

It wasn't long before a firm reply came back. "The men thank you for thinking of them but we are the last of the Royal Yugoslavian Air Force. The wounded can't bail out so we have decided to go together, if that is the way it is to be."

A voice from Group Headquarters came over the Command Radio, "This is Colonel Graff, Group Commander! Captain Skakich and his crew are to bail out! Do not try to land on autopilot. THIS IS AN ORDER! Confirm! I repeat, do not land with auto-pilot, confirm!"

"Skakich to Colonel Graff. Our crew has made up its mind and we are sticking together, come what may."

"Graff to Skakich, you can risk you ass if you want to for your wounded, but I insist and order that everyone else bail out. You can keep a co-pilot or engineer. Is that clear? Confirm!"

"Sorry, Sir, but we are all going in together."

There was a pause. Colonel Graff came back on the radio.

"Skakich, report to me when you get down and.and good luck."

We flew to the South of the Airbase at an altitude of2,500 feet. With the No.3 engine feathered, Skakich's plane was without hydraulic pressure in the system so the flaps and wheels had to be lowered by hand cranking. It also meant there may not be any working brakes when they landed.

By experimenting, the Yugos were able to lower flaps and wheels and adjust the autopilot for a gradual let down. So far so good! Captain Skakich made a slow 1800 turn to the left away from the dead engine and headed for the Base.

"You're looking good with wheels and one-quarter flaps down! Guess we are about 5 minutes out from the field," I said enthusiastically but knowing the real test was yet to come.

On the final approach the Yugos fired red flares indicating an emergency on board and to warn off any other planes that might be planning to enter the landing pattern.

When their plane was approaching the end of the runway, Skakich cut the power, dropped full flaps and nosed the B-24 down toward the runway. At first the big lumbering bomber refused to land. One third of the runway whizzed past before the main wheels settled on the surface. The nose wheel came down hard as the brakes were applied. Captain Skakich knew he would have trouble stopping in time so he pressed hard on the brake pedals causing the wheels to drag and the tires to smoke.

The runway was being used up fast. Everyone on the Base who was aware of the drama unfolding held their breath as the heavy bomber skidded to the end of the runway and stopped. As the dust and smoke cleared, the crash crews were relieved there was no fire. By the time they arrived at the plane, the proud Yugoslavians were passing their wounded through the escape hatches and open bombbay doors.

I pressed my throttles forward and started a climbing turn away from the scene below and waggled my wings at this victory over death.

After landing and pulling my plane into the parking ramp, I saw a jeep full of men coming toward us waving their arms and yelling. As soon as I climbed out through the open bombbay, the Yugoslavians greeted me, all talking at once. I was grabbed, shaken, lifted and patted by obviously happy men celebrating a victory.

Captain Skakich asked for silence and with a voice choked with emotion, explained that in Yugoslavia, men join the Armed Forces to die for their country if necessary and the wounded are left in the field to fend for themselves. He said, "Lieutenant Burton, your willingness to risk the safety of the formation and the extra effort you went to in order to bring us home was something we have never experienced before nor did we expect it. We are very grateful."

I was surprised by his comment and didn't feel I had done anything particularly heroic.

"Listen, Captain," I said, "I'm glad it worked out so well but you and your crew are the real heroes, bringing that busted-up B-24, 600 miles and landing on autopilot. It was a hell-of-a-job of flying."

We shook hands all around and I could see the real comradery in their crew. They were professional, dedicated men proud of their association with the U.S. Army Air Corps in the war against the Axis Powers.

A few days later, Captain Skakich called me over to his tent where the other members of the Royal Yugoslavian Air Force were gathered in an attitude of expectancy.

I saluted Captain Skakich.

"Lieutenant Burton, I notified His Royal Highness, King Peter of Yugoslavia, now in exile in England, of your willingness to risk the lives of Americans to save us from death or capture. He has expressed his most sincere appreciation and as a token of his gratitude hereby makes you an honorary member of the Royal Yugoslavian Air Force."

67

Captain Skakich then pinned a pair of gold and silver wings of the Royal Yugoslavian Air Force over the right pocket of my U.S. Air Corps jacket.

It was a proud and emotional moment and the words of appreciation stuck in my throat. Our eyes met as we shook hands and a current of understanding was felt between us which only men who have daily shared or lived on the sharp edge of catastrophe can recognize and comprehend. I nodded my thanks and shook the hands ofthe rest of the Yugoslavian aircrews. I was now a member of this group of proud flyers!

Later in the Officer's Club, we toasted each other, wishing each the successful completion of 50 missions.

Throughout the rest of my experience in the Air Corps, I proudly wore the Yugoslavian pilot's wings and remembered the brave men who fought the war but lost their country. As a young man of 21, I had been a part of a unique historical experience in flying with and becoming an honorary member of the last of the Royal Yugoslavian Air Force.

I was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for saving one of the last crews of the Royal Yugoslavian Air Force.

EPILOGUE

Forty-two years after World War II ended, I attended a reunion of the 376th Bomb Group in Las Vegas, Nevada. I wore the Royal Yugoslavian Air Force wings on my cap and hoped someone would recognize them and let me know what happened to the Yugoslavians after the war. To my good fortune, there were two Yugoslavians at the same reunion, Joe Milloy and A.T. "Shorty" Trailov.

Joe Milloy, a member of the Yugoslavian crew recognized the wings and was surprised I had a pair of the original wings that must have been donated by one of the Yugoslavian pilots. He said that copies of their wings had been made in Egypt and given to American officers in the 15th Air Force but they could be recognized. It made me all the more proud of these wings I have worn and cherished over these many years.

Shorty Trailov told me how to get in touch with Captain Skakich. My story brought back many memories and we had a long talk about the days at San Pancrazio, Italy.

I called Captain Skakich by phone and he recalled the mission I related here but he thought some of the details were different than I described. Forty-six years can have an effect on one's memory but I feel the facts I have related are true but the dialogue may not have been the same. I have purposely expanded the dialogue between the pilots to give the reader a better understanding of what was going on. Radio conversations between planes in combat were very limited. The fact is, we did escort them home.

So far, the following members of the Royal Yugoslavian Air Force have been located:

Captain "Voya" Skakich living in Aurora, Colorado. Lt. "Joe Milloy" living in Ft. Washington, Maryland. A.T. "Shorty" Trailov residing in Maui, Hawaii.

According to Captain Skakich, Colonel Theodore Graff, Brig. General Richard W. Fellows and Lt. General Robert H. Warren arranged through their contacts in Washington D.C. to have Congress pass special legislation to make the surviving Yugoslavian flyers U.S. citizens instead of refugees.

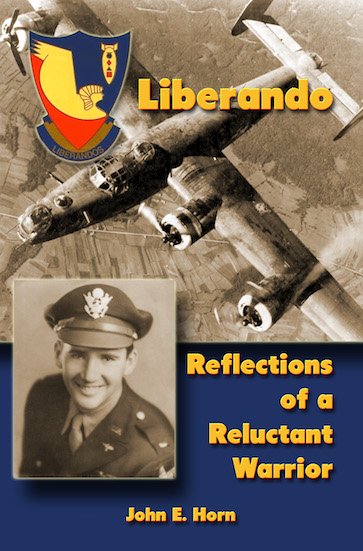

The following is an excerpt from the March 1947 "Liberandos", the 376th Heavy Bombardment Group Veterans Association's publication, titled "GRATITUDE PLUS JUSTICE".

"Of interest to all former 376th men, is a bill introduced by Senator William E. Jenner of Indiana to grant naturalization to several of our comrades-in-arms overseas, the Yugoslavian airmen. Senator Jenner feels as we do 'that our government owes a debt of gratitude to these young men and to pave the way for their naturalization is a small measure of repayment'.

"Several months ago, in Washington D.C., our Yugoslav comrades were denied citizenship by a judge who felt that this government owed them nothing. For this reason the U.S. Senate was called upon to see that justice was done. Without being bitter, we wonder if our comrade's effort to gain citizenship wouldn't have been easier if they hadn't participated in a war against both Fascism and Communism. The United States needs more citizens of the type of our Yugoslav friends and less of the kind that would tear our form of government apart.

"Senator Jenner has assured us that the Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee has the naturalization bill under consideration and that it will be moved forward.

"Four former members of the Royal Yugoslavian Air Force, Captain Vijislav Skakich, 1st Lt.'s Milosh Jelich and Zivko Miloykovich, and F/O Dejan Radich have been given honorary membership in the 376th HBG Veterans Association."

The Yugoslavians obtained their citizenship and finished out their careers in the U.S. Air Force.

Recently, the Author, David Burton, was asked to be the Master of Ceremonies for installing a Memorial Plaque honoring General Mihilovich. It was located in the Eastern Orthodox Cemetery in Colma, California. Following the ceremony, a banquet was held in Palo Alto, California for the Yugoslavians that were fighting in the war against the Nazi and each other. Some hard feelings were expressed between the adversaries.

At the banquet, I was impressed by a story told by an American Pilot, who said his crew was rescued by General Mihilovich's army. He related how they were in the mountains above a small village when the Germans notified Mihilovich that if they didn't give up the American airmen, they would destroy and kill all of the nearly 200 residents of the village.

The story goes that Mihilovich responded, "You Americans are more important to the war effort against the Nazi Germans than the poor residents of that village. We want you to go back and bomb the Germans again." He refused the German offer.

The Germans carried out their threat.

The American Airman telling that story said he watched from the mountains as the village was destroyed. He could not hold back the tears when he related what happened that day.

The website 376bg.org is NOT our site nor is it our endowment fund.

At the 2017 reunion, the board approved the donation of our archives to the Briscoe Center for American History, located on the University of Texas - Austin campus.

Also, the board approved a $5,000 donation to add to Ed Clendenin's $20,000 donation in the memory of his father. Together, these funds begin an endowment for the preservation of the 376 archives.

Donate directly to the 376 Endowment

To read about other endowment donation options, click here.

Reunion

NOTE change in the schedule !!

DATES: Sep 25-28, 2025

CITY:Rapid City, SD

HOTEL: Best Western Ramkota Conference Hotel; 2111 North LaCrosse St., Rapid City, SD 57702; 605-343-8500

Click here to read about the reunion details.