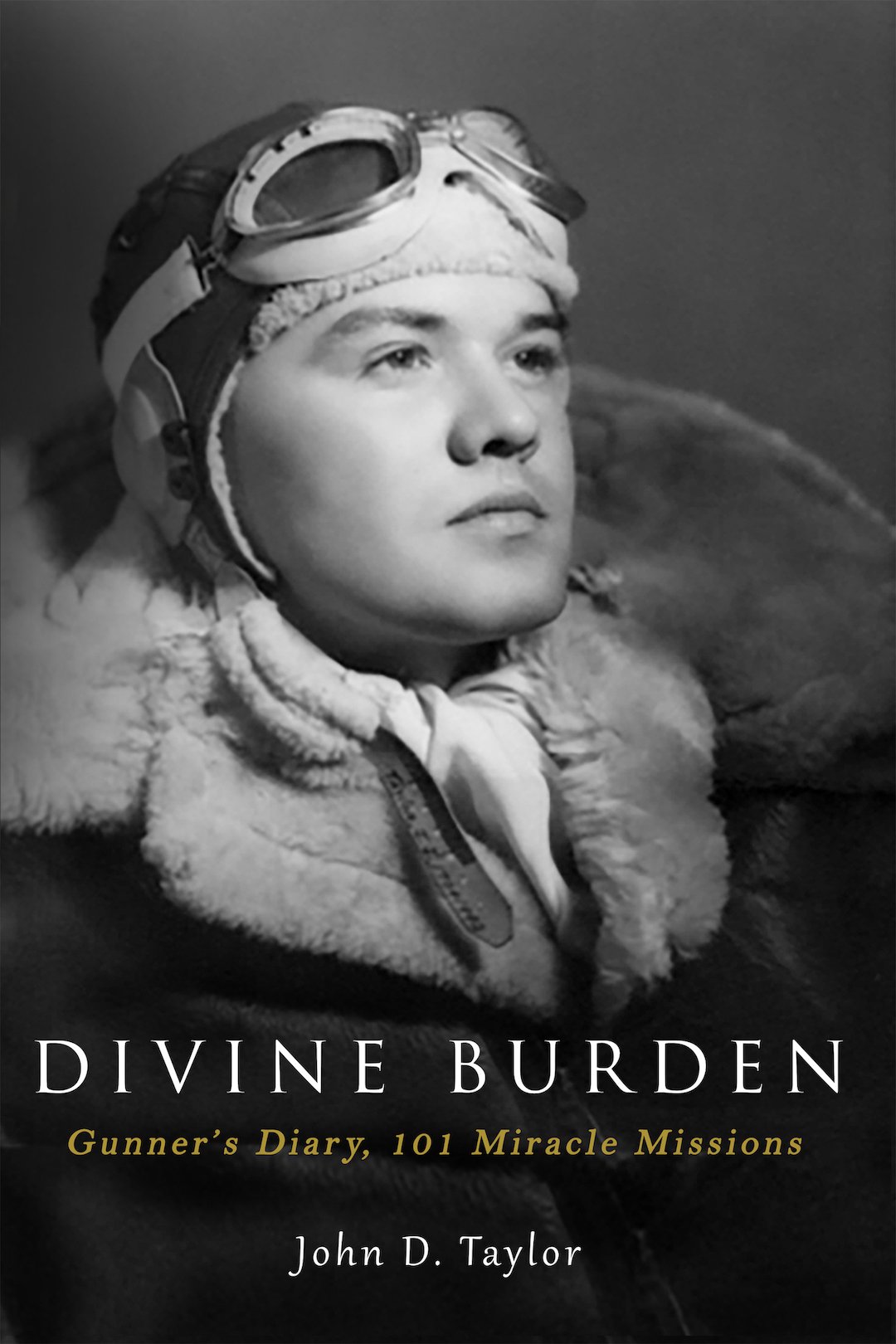

Harold Christensen

Harold Christensen was the tail gunner on the Norm Appold crew.

Harold wrote an article, entitled "The Last Flight," that was published in the Summer 1985 issue of JOURNAL of the American Aviation Historical Society. It was about his experiences.

The title refers to the mission on October 6, 1942. Click here to read that story.

The rest of the article follows:

The resounding "Bah-rhoom" of the exploding 20mm cannon shell reverberated in the small confines of my tail turret. The pain was excruciating as the shrapnel tore into my lower right leg and when the pungent fumes of cordite arose and reached my nostrils, I almost retched. The German Messerschmitt lO9G fighter plane was now just a blur, and with a loud "Swoosh" it disappeared beneath our tail.

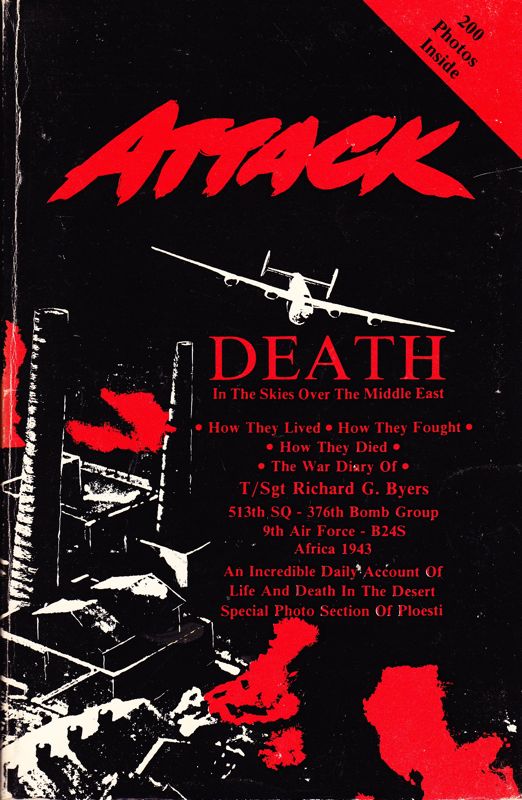

Since General Rommel's arrival in the Middle East, this brilliant military strategist had led his troops ever eastward across the Sahara. The beleaguered British Eighth Army was valiantly striving to stop their advance for the Nazis now threatened Cairo and the vital Suez Canal.

Later when Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery rook over the command of the Eighth Army. The tide of the battle changed and the Nazis were stopped at El Alamein and the Afrika Korps was subsequently defeated.

Marshal Montgomery certainly deserves a lion's share of the credit for this victory. However, the B-24 Heavy Bombers of the Ninth U.S. Air Force, both from the 98th Heavy Bombardment Group as well as our own 376th Bomb Group never received the full credit that they deserved. The British controlled me press in the Middle East Theatre of Operations and I vividly recall one Cairo newspaper headline "R.A.F. Planes Blitz Libyan Port" Hell, the RAF didn't have a single airplane on that raid! It was our 376th Bomb Group that flattened the seaport town of Tobruk. So much for wartime propaganda.

The Ninth U.S. Air Force made a major contribution in the Middle East Theatre in that it helped to stem the flow of fuel, ammunition and other vital supplies destined for the German forces and Rommel's once seemingly invincible Afrika Korps slowly ground to a halt.

The first time I ever saw a B-24 Liberator Bomber was on a mid-summer day at Barksdale Field (now AFB). Shreveport. Louisiana. The year was 1942. I had just graduated from the Aerial Gunnery School at Tyndall Field. Florida. When I arrived at Barksdale I was instructed to report to a 2nd Lt. Norman C. Appold over in the hanger area. My future crew was gathered underneath the wing of a huge, squat, cumbersome looking airplane a B-24D Heavy Bomber.

After saluting Lt. Appold. I introduced myself. He then informed me that I was to be his tail gunner.

"But, sir. I've never been aboard a B-24. What kind of a turret is it?"

“It's an Emerson tail turret."

"But, sir, I don’t know how to operate one."

"That's all right, son. We’ll teach you on the way over."

Although the pilot had addressed me as "son," at 25 he was only a year older than I. So I was to receive my tail turret indoctrination on the way overseas, nor realizing that we were about to embark on a flight of over 12,0OO miles, circumnavigating more than a third of the globe!

Our crew consisted of the pilot, 2nd Lt. Appold from Detroit, Mich.; copilot 2nd Lt. Clark Gerry; navigator 2nd Lt. Donn Odell, Los Angeles, Calif.; bombardier 2nd Lt. John V. Hogan, Brooklyn, N.Y.; crew chief/waist gunner Frank Yakimovicz; radio operator top gunner Charles S. Anderson, Malakoff, Texas; waist gunner Raymond Weipert; and myself as the tail gunner. Frank and Charles were corporals and Ray and I were privates. Looking back in retrospect, it is a minor miracle that a crew as inexperienced as ours certainly was, ever made it safely past our first mission!

The next morning we took off for Morrison Field, West Palm Beach, Fla. where we were outfitted with high altitude flying gear, .45 caliber pistols, oxygen masks and machines.

Two days later, with an ominous sky overhead, we took off, ostensibly for South America. However, we encountered a fierce Atlantic storm and as skillful and resourceful a pilot as Norman Appold was, we just couldn't make headway through the rain, sleet, and hurricane winds generated by the storm. So reluctantly, Lt. Appold turned and headed back for Morrison Field.

The next morning the weather was not quite so inclement and we got off without incident and headed for our first overseas stop, Belem in Brazil. After landing in Belem we welcomed a hot meal after the long flight from Florida. Our stopover was brief and after refueling we headed for our Atlantic jumping off spot: Naral. Brazil. On that leg of our journey the pilot flew at a lower altitude and we could clearly see how dense and seemingly impenetrable was that part of the Brazilian jungle as we skimmed the treetops at less than 500 feet. I then realized why we had been issued machetes because if we managed to survive a forced emergency landing there, we would have had to hack our way through the thick underbrush.

As soon as we landed in Natal we headed for the showers with the anticipation of another welcome hot meal after we refreshed ourselves. From a geographic standpoint, Natal was the shortest distance from the two continents: South America and Africa to our destination in Accra, Ghana.

After a two day rest in Natal, we refueled, put aboard food supplies and headed out across the broad expanse of the South Atlantic. Knowing what a long flight lay ahead of us, I remember saying silently to myself: “Christ I wander if we'll make it.

I must have killed quite a few of the fish indigenous to that part of the Atlantic for I then received my first instructions on how to operate the tail turret from Lt. Appold. After showing me how to turn on the turret and manipulate both the turret and fire the twin .50 caliber machine guns, the pilot said I could practice firing at the waves below as soon as I received an all clear signal from Lt. Gerry, who was now flying our bomber. The pilot stressed the importance of firing short bursts so as not to burn out the barrels of the guns. So during our 11 1/2-hour flight across the Atlantic I had plenty of time to practice and familiarize myself with the controls of my turret.

It was also a time for retrospection. During some of the time that I spent in my lonely vigil in the turret, ever on the alert for German submarines, I would look westward across the vast expanse of ocean and the many miles that separated me from my brother John, my mother and my father in San Francisco, Calif. wondering how they were. We hadn't received any mail from home for some time now because of our constant hopping from one point to the next.

My Mother was a worrier and as proud as she was of my enlistment in the U.S. Army Air Corps, she was constantly concerned about my welfare. So I was glad that my brother was there at home for consolation. Due to a physical ailment my brother was unable to enlist in the service, much to his chagrin. He was a gifted craftsman and worked as a marine draftsman in a San Francisco shipyard. My father was a rough, tough, ex-sea captain so he was also able to downgrade any hazards that my mother thought I might face. But I couldn't afford to reminisce any longer as I had to concentrate on the task at hand and prepare myself mentally for whatever lay ahead.

I still didn't know our final destination. The closest battle front was in the Middle East so we had guessed correctly that was where we were going. The pilot didn't brief us on the overall flight plan. He merely told us of our next stop just prior to takeoff.

When the pilot announced on the intercom that we were approaching the coast of Africa, I rejoined the two waist gunners, Frank and Ray, amidships. We discussed how great it would fell to again get off the bomber and stretch our legs on good old terra firma. It had been a long and arduous flight and I'm sure that they were as relieved as I was that the most hazardous part of our journey would soon be behind us.

Our stay in Accra, Ghana, was of short duration and early the next morning we headed for Khartoum, Sudan. After a lengthy flight across the heart of the African continent we landed, and as we stepped down from the plane. It was as though we had stepped inside a blast furnace. The temperature that day in Khartoum was 124 degrees! We couldn't get into the showers fast enough.

When the officers returned from preflight briefing, the pilot informed us that we were headed for our first base Haifa, Palestine, (Israel). Now the excitement we had all felt the past few days as we neared the end of our journey mounted as it meant that we would soon be engaged in combat. I looked forward to our first combat mission with a mixed feeling of awe and in trepidation. I now realized that the next time I faced my guns someone would undoubtedly fire back and try to blow me right out of my tail turret!

As we headed north two days later we gazed down upon the Nile River as it meandered northward in the same direction that we were going. After a long flight we finally saw the Mediterranean stretched out below, and followed the coastline northeast to our destination.

When we sighted Tel Aviv the crew that the next town of any consequence would be Haifa.

Shortly after landing at the Royal Air Force Airdrome, several miles inland, we were assigned quarters in a Quonset hut with a corrugated tin roof. We were then treated to a hot meal, British style. The English don't have much imagination in the preparation of food. At least not at that base. Our menu seldom varied from two staple items: bully beef (vaguely similar to corned beet) and mutton stew. But famished as we were, the Piece de resistance of that day, mutton stew, soon disappeared from our mess kits.

Airmen, like sailors, develop a kinship for their particular mode of transport. So it was disheartening news that Andy (Charles Anderson) and I learned the next morning when we asked the skipper (Andy and I had already applied that sobriquet to Lt. Appold and later Andy was to refer to our pilot as "Johnny Appleseed," albeit respectfully) where our plane was parked.

It was then that we suffered one of the many dis-illusionments in store for those who set out to fight a war. The pilot informed us that the brand-new bomber, fresh out of the Consolidated plant at San Diego, Calif., was already being dismantled and the four Wright Cyclone engines were to be used for spare parts. It was considered simply the most feasible way to obtain spare parts: fly the planes overseas and just take what parts were needed. We all had had visions of giving our bomber a name and perhaps even painting a picture on her nose.

As for the glamour and romantic aspects of war, that was one of the first lessons we learned, however minor, that man's inhumanity to man can be impersonal and callous.

We were one of several crews that had recently arrived to form the 514th Bombardment Squadron of the 376th Bombardment Group. However, at that juncture of our existence, due to the fact that our group had been so hurriedly assembled we didn't, at that time, even have a numbered designation. We were simply known as the Halverson Project. That was later shortened to Halpro just prior to our becoming the 376th.

The reason for this hectic activity was because it had been decided at Ninth United States Air Force Headquarters in Cairo, Egypt, in conjunction with British Royal Air Force leader, Sir Arthur Tedder, that Field Marshal Erwin Rommel's German Afrika Korps' supply lines had to be disrupted. The best way to do that was with the use of heavy American bombers to bomb German and Italian supply ships as they unloaded in the Libyan ports of Tobruk and Benghazi.

As our group was not as yet fully assembled Lt. Appold said that we could go into Haifa on pass, so Andy and I took off for that beautiful seaport town. Charles Anderson and I found that we had a lot in common, one being that we both loved sports, especially football. We became very close friends. We brought along our swim trunks and a football and almost every day for the next two weeks we tossed a football, sunned ourselves on the wide, incredibly white clean sandy beach and swam. Coming from California, I was accustomed to wide sandy beaches. especially those in Southern California. But I've never seen beaches as beautiful as those in Haifa and Tel Aviv. And at that time the Mediterranean was such a deep blue and the water was so clear, warm, and clean that swimming there was not unlike cavorting in the warm waters of an immense bathtub!

Our idyllic beach sojourn soon came to an end, however, as we were scheduled to fly our first combat mission two days hence. Then tragedy struck with a suddenness that staggered all in our group. Early on the morning after the posting of our bombing mission, one of the bombers in our squadron (514th) inexplicably exploded on takeoff. It was also that crew's first mission and we knew all of those aboard. Our immense sorrow was assuaged, but only slightly, with the knowledge that the entire crew must have died instantly. The bomber was carrying five 1000-lb. bombs and the forward bomb bay was equipped with huge tanks filled with high-octane gasoline. Other than a large crater at the end of the runway, little else remained to mark the tragic occurrence. I was tense and uneasy as I watched the ground skim past as our bomber accelerated down the runway on our first bombing mission the following morning. I was looking out the waist window, as were the two waist gunners, Frank and Ray. It was the same runway where tragedy had struck yesterday and I felt a great sense of relief as we suddenly became airborne.

Our missions over Tobruk and Benghazi in Libya were destined to be 10- and 11-hour affairs. So the forward bomb bay was fitted with a large fuel tank. Today we were carrying five l,000-lb. high explosive bombs. To compensate for the heavy load and to ensure that we lifted off safely, Lt. Appold would press down on the controls until we had reached maximum speed. He would ease back on the controls near the end of the runway and as he later explained to us, the bomber would “jump off” the ground. He must have had the correct formula because our takeoffs were almost always just about perfect.

Norman C. Appold of Detroit, Mich., always seemed to me to be a contradiction of terms, as I considered him to be both a "cool cat" and a "hot pilot." A "cool cat" because he was absolutely fearless. There were many missions when the flak (88mm antiaircraft cannon fire) got so damn close that we could actually feel the concussion from the exploding shells! But during those highly stressful times, Lt. Appold would get on the intercom (intercommunication phone system), ask all stations to report and in an absolutely calm, unperturbed voice would ask. "How's it going, lads? It's pretty rough right now, but stay steady. We'll be out of here soon," then he'd abruptly sign off. I would always respond by asking myself. Why in hell should I be scared. that guy up front certainly isn't. It invariably had a calming effect on all of us.

Click here to read Harold's recollection of the Aug 24, 1942 mission.

Several missions later, an experience I had changed my evaluation of aerial gunnery. It was on a night mission over Benghazi and when the searchlights probed the sky and finally found us I saw a twin-engined German Messerschmitt 110 night fighter climbing up toward us from the rear. I reported it to the pilot and when the German got within range I opened fire with my twin .50-caliber machine guns. My tracers followed his path of flight and it looked like I was scoring direct hits with my short bursts. The night fighter continued his climb and when he got high above us the German pilot barrel-rolled and dove earthward, apparently in full control and undamaged.

Andy and I talked about that encounter after the mission and comparing notes we decided that my tracer bullets were passing underneath the enemy fighter. When the fighter came into Andy's line of view from his top turret, his line of sight allowed him to have a better view of where my tracers were headed. So we both decided mar my trajectory was too low and whereas it had appeared to me that I was scoring direct hits, my tracers were sailing harmlessly below me climbing night tighter. So on subsequent missions I arranged to be out at our bomber about an hour and a half before we were scheduled to take off. I had asked the armorer not to load my .50-caliber ammunition into the turret, but to merely place the belts of ammunition on the deck in the waist of the plane. I then removed all the tracer and ball bullets and replaced them with armor piercing, explosive and incendiary bullets.

I would like to note at this juncture that in addition to his exceptional skill as a pilot, Norman Appold was an exceedingly warm, considerate and personable guy.

Charles Anderson had developed into a very proficient radio operator and we could always be assured that crew chief, Frank Yakimovicz, would have our bomber in tiptop shape and ready to go prior to each mission. Yet they both remained corporals. Waist gunner Ray Weipert and I hadn't done too poorly in the performance of our duties either. Yet we remained privates.

We now had eight combat missions under our belts but replacement crews were arriving from me States as buck and staff sergeants and they had as yet to fly their first mission. So we took our case to the pilot. Lt. Appold's answer was, "Well, lads, I'm going right in to see the C.O. Even if I have to come out busted down to a private. I'm going to see that you lads get your stripes."

The following morning a notice was posted on our bulletin board. We had all become instant sergeants!

The website 376bg.org is NOT our site nor is it our endowment fund.

At the 2017 reunion, the board approved the donation of our archives to the Briscoe Center for American History, located on the University of Texas - Austin campus.

Also, the board approved a $5,000 donation to add to Ed Clendenin's $20,000 donation in the memory of his father. Together, these funds begin an endowment for the preservation of the 376 archives.

Donate directly to the 376 Endowment

To read about other endowment donation options, click here.

Reunion

NOTE change in the schedule !!

DATES: Sep 25-28, 2025

CITY:Rapid City, SD

HOTEL: Best Western Ramkota Conference Hotel; 2111 North LaCrosse St., Rapid City, SD 57702; 605-343-8500

Click here to read about the reunion details.