Harold Christensen

Harold Christensen story about the mission on Oct 6, 1942.

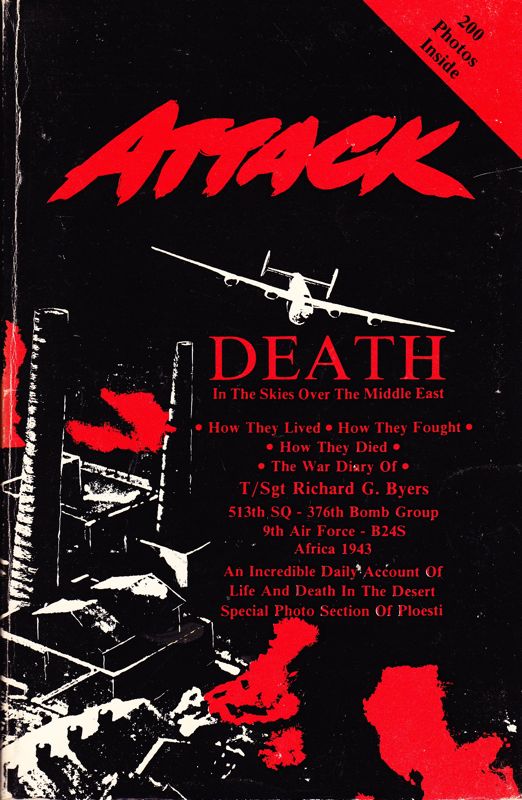

It was October 6, 1942, and I was aboard a B-24D Heavy Bomber serving the 514th Bombardment Squadron of the 376th Bombardment Group, 9th United States Air Force. We were then stationed at a Royal Air Force station, Abu Sueir Airdrome in the Sahara Desert, 85 miles northwest of Cairo, Egypt. We had just finished our bombing run, and our targets were Italian supply ships unloading their cargo of gasoline in Benghazi Harbor, Libya. The Axis forces were funneling supplies from Italy to bolster General Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps in the Western Desert. More about the “last flight" later.

Our crew consisted of the pilot, 2nd Lt. Norman C. Appold from Detroit, MI; copilot, 2nd Lt. Clark Gerry; navigator, 2nd Lt. Donn Odell, Los Angeles, CA; bombardier, 2nd Lt. John V. Hogan, Brooklyn, NY; crew chief/waist gunner, Frank Yakimovicz; radio operator/top gunner, Charles S. Anderson, Malakoff, TX; waist gunner, Raymond Weipert; and me as the tail gunner. Frank and Charles were corporals and Ray and I were privates. Looking back in retrospect, it is a minor miracle that a crew as inexperienced, as ours certainly was, ever made it safely past our first mission!

We were one of several crews that had recently arrived to form the 514th Bombardment Squadron of the 376th Bombardment Group. However, at that juncture of our existence (due to the fact that our group had been so hurriedly assembled) we didn't, at that time, even have a numbered designation. We were simply known as the Halverson Project. That was later shortened to Halpro just prior to our becoming the 376th.

On that last fatal flight over Benghazi on October 6, 1942, we were the next-to-last bomber, of a flight of ten B-24's, to leave the target area. Three Messerschmitt 109G's pounced on the last bomber which had just made its bombing run. Norman Appold decided to turn back and try to assist our beleaguered comrades. We joined the other B-24 and flew alongside, wingtip to wingtip so as to consolidate our fire power. As the fighters came in to attack; theoretically, we would have them in a wicked crossfire. But the first German concentrated on the other bomber, and its tail turret sustained a hit on the bulletproof glass shield just in front of the tail gunner. The cannon shell didn't penetrate, as it was only a glancing look, but their tail gunner panicked and crawled out of his turret as he deserted his post. So much for the crossfire theory.

When the pilot of that other B-24 learned of his tail gunner's cowardice, he immediately banked, went into a steep dive and headed for home, leaving us to the mercy of the three Nazi fighters. It was ironic, but the crew that we went back to try and save escaped without a scratch and we were about to get shot all to hell!

The three ME 109's were now flying in formation just out

of range of my machine guns, several thousand yards away and slightly above the

level we were flying. Behind them tremendous puffy piles of brilliant white

cumulus clouds rose layer upon layer. Their columns spiraled ever upward until

they were finally draped in contrast against the deep blue morning sky. It

didn't seem possible that violence and hatred would exist amid this exquisite

celestial splendor.

Suddenly the staccato "boom, boom, boom” of cannon fire shattered my reverie as one of the fighters peeled off and dove straight in toward my turret. The 20mm tracer shells from its wing guns looked like so many blurry golf balls as they headed toward me. It was then that one of the cannon shells exploded in my turret, severely injuring my right leg. But I kept firing and as the enemy plane loomed ever larger in my gun sight I thought, Christ, he 's gonna fly right into my turret!

The adrenalin was now pumping so fast that I was only faintly aware of the throbbing pain in my leg. I aimed for the yellow spinner on the fighter’s nose section and fired short bursts. Suddenly, thick white smoke poured forth under its nose indicating that my slugs had ruptured its glycol liquid coolant tank (I was informed by a Royal Air Force pilot, whom I later met in the Royal Air Force hospital in Cairo, that with the ME 109’s coolant expended, its engine would overheat and explode in a matter of but a few minutes). The ME 109 shot straight up behind us, barrel-rolled a few times, and then dove earthward out of sight.

But something else drew my attention. Smoke! But this time the smoke was jet black. A cannon shell had found one of our port side engines, and it was now on fire! The dark smoke billowed past our left vertical stabilizer, and the thick black swirls trailed back as far as I could see. Gradually, the color of the smoke lightened, and it finally became a thin snakelike wisp as copilot Clark Gerry had managed to extinguish the blaze.

Meanwhile, the top turret, just aft of the flight deck manned by Sgt. Charles S. Anderson, had been damaged and was totally inoperable. Luckily, Andy had not been injured. He climbed down from his turret to see if he could be of any assistance in the waist. When he stepped through the bomb bay entrance, he was shocked by what he saw. Huge chunks had been torn in the sides of our bomber. Then Andy saw Sgt. Raymond Weipert lying in an inert heap beside his .50-caliber machine gun. Ray’s head lay in a crimson pool of his own blood. It was later judged that a 20mm cannon shell had passed through my tail turret directly over my right-hand gun, traveled amidship, and tore off the top of Ray’s head.

If the reader is stunned by my brutally graphic description, so be it. However, my intention was not to stun but to realistically report a tragic incident that illustrates the utter futility and beastliness of man’s inhumanity to man.

The other waist gunner, Sgt. Frank Yakimovicz, had a jagged shrapnel wound to his cheek. The blood was slowly trickling down and staining the front of his heavy flying jacket. However, Frank was still manning his gun, and so Andy motioned to him that he was going aft to the tail section.

Andy knocked on my turret door, and when I opened it, I was shocked by his appearance. His face was ashen and drawn. His glazed, vacant eyes mirrored an anguish that I now find impossible to either adequately describe or completely forgot.

"Andy~ what'n hell 's wrong?"

"Christ~ with all the holes in your turret. I was afraid to look in." he replied.

“You been hit?” he wanted to know.

“Yeah~ I got it in the leg."

"Well ~ then get your ass outta that goddamn turret” Andy harshly demanded.

"I'm not gettin' outta here 'til the pilot tells me to." I then reached for my intercom phone. But Andy grabbed my arm and snapped, “Forget it, Chris. The whole stinkin' system's been blown out."

I started to say. “Is everyone else all right?” but before I could finish~ Andy stammered bitterly, "Ray had the top of his head blown off!”

He looked at me sadly for a moment and then slammed the turret door shut. I was shaken by the news of Ray's death.

With one gunner dead and the other turret disabled, I had to immediately assess our situation and do what had to be done to get us the hell out of there so we could head for home.

The two remaining German fighters were flying wingtip to wingtip several thousand yards to our rear. They were just out of range -- waiting and looking not unlike two ominous buzzards ready to swoop in for the kill. Finally, one made a tentative pass, breaking off just before he got within range. With a wide sweeping turn, he rejoined his partner.

As he had approached. I discovered that when I fired several short bursts and started tracking him as he made his turn that my turret wouldn't turn completely to the right. The worm gear on which the turret rested had been damaged by the cannon fire that had resulted in my being wounded. The two Nazi s appeared to be out of ammunition as they ceased their attack. But to make certain they didn't realize that my turret was damaged, I raised and elevated my guns and fired sporadic bursts in their direction. Then they broke formation, peeled off, and disappeared from view.

A short while later, my turret door opened and copilot Clark Gerry peered in and in a gentle voice said. "Come on. Chris. Let's get you out of there and have a look at that leg."

Andy had joined him, and with their assistance, I clambered out and hobbled back to the waist, hanging onto their arms. They laid me on a blanket and Lt. Gerry injected a shot of morphine into my upper arm. When he cut away my pants leg. I looked down at the wounds in my lower right leg and I was fascinated by the blood that was slowly oozing from the four holes and I thought, I sure have healthy looking blood! The copilot expertly bandaged my leg, and it was then that I looked over to where Ray Weipert was lying next to me. I'll never know why, perhaps I was prompted by morbid curiosity or was in a mild state of shock~ but I reached across and started to lift a corner of the blanket covering Ray when Andy gently took hold of my wrist and said softly. “No Chris. You don't want to look. Ray's gone."

There are certain events in our lives that are more memorable than others and are not easily erased. That scene will be forever etched. In my memory, I'll never forget Raymond Weipert. How could I?

Our bomber was a mess. Number 2 engine was disabled. Sections of the left aileron and left rudder were torn away, formers and ribs of the vertical stabilizers were shot away, and the interphone communication destroyed. And the wind was howling through the gaping holes that had been torn in the fuselage. Despite this extensive damage, Norman Appold managed to nurse our crippled bomber along and flew it an incredible 1,000 miles back to our base at Abu Sueir Airdrome, Egypt. When we finally arrived at the landing field and Lt. Appold made his final approach, he discovered, due to damage to our horizontal stabilizers, that he had difficulty lowering the nose of the plane in order to make our descent. So when he reached what he decided was the proper distance from the end of the runway, Lt. Appold cut the power, glided in, and made an almost flawless landing!

I'll be ever thankful that a pilot with the expertise and resourcefulness of Norman Appold was at the control s that day, for he undoubtedly saved all of our skins. As TV commentator/columnist Andy Rooney once noted in his newspaper column (describing the skill of a close friend who was a B-17 bomber pilot in World War 11): "He had the coordinated grace it took to fly a four-engine bomber." It seems that Norman Appold was blessed with that same trait.

After we had landed, I was placed on a stretcher and was eased into a waiting ambulance. Several officers and the bomber's ground crew were scurrying around our damaged bomber, surveying the damage and attempting to count the holes in the fuselage, wings and tail section. I learned later that they gave up the count. There were simply too many holes.

A major from the engineering section of our group walked up to Lt. Appold and asked, "Are you the pilot of this wreck?" When the pilot nodded affirmatively, the major said, "Lieutenant, you had no business flying as far as you did in this pile of junk. Hell, it just isn't flyable."

With that he grasped my pilot's hand, shook it vigorously, and respectfully intoned, "Son, you're one helluva pilot, and you did a fantastic job getting this crate back in one piece. My congratulations."

The website 376bg.org is NOT our site nor is it our endowment fund.

At the 2017 reunion, the board approved the donation of our archives to the Briscoe Center for American History, located on the University of Texas - Austin campus.

Also, the board approved a $5,000 donation to add to Ed Clendenin's $20,000 donation in the memory of his father. Together, these funds begin an endowment for the preservation of the 376 archives.

Donate directly to the 376 Endowment

To read about other endowment donation options, click here.

Reunion

NOTE change in the schedule !!

DATES: Sep 25-28, 2025

CITY:Rapid City, SD

HOTEL: Best Western Ramkota Conference Hotel; 2111 North LaCrosse St., Rapid City, SD 57702; 605-343-8500

Click here to read about the reunion details.