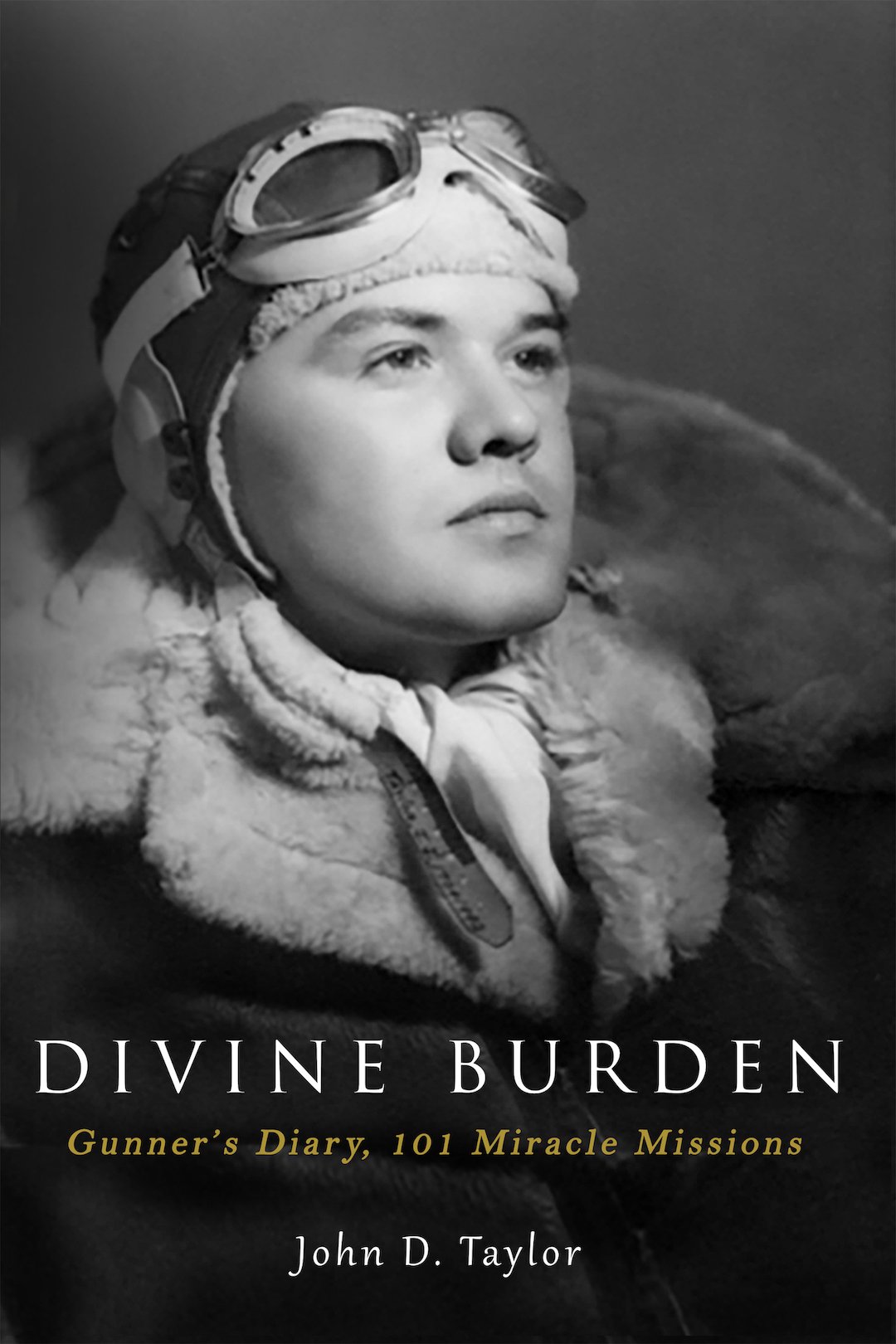

Ernest Fogel

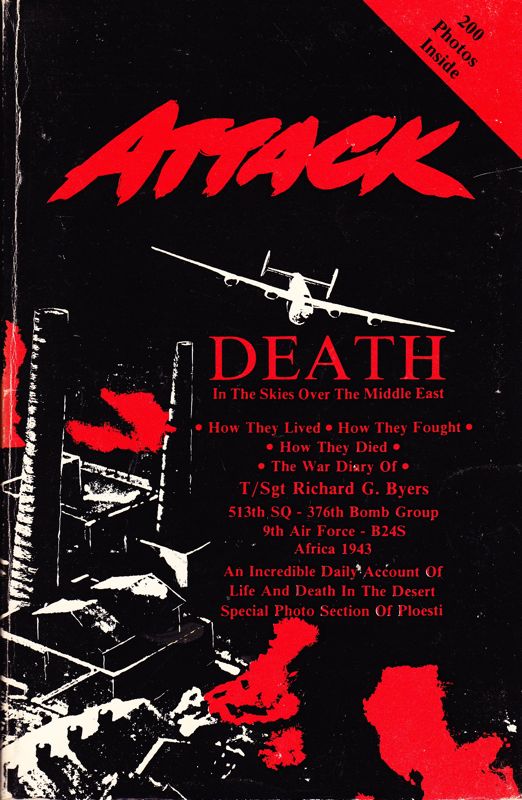

Ernest Fogel and crew were assigned to the 513th squadron.

The following article appeared in the Sunday, May 28, 2000 issue of the "Corpus Christi Caller-Times". It was entitled

WWII aviator Ernest Fogel shares his diary, bittersweet memories for Memorial Day

and was written by Darren Barbee.

May 4, 1943. Ho boy! What a day!

The German ME 109s leapt from nowhere, taking turns stinging the American bomber's nose and tail.

The agile, quick-tempered single-engine fighters with their high-powered engines could fly at 347 mph. The vulnerable B-24 plodded along at 165 mph.

Ernest Fogel's plane was headed back to North Africa after the thick cloud cover over southern Italy had spoiled the bomb run. Somehow, Fogel had been separated from the main formation of 22 bombers, which were drawn close together in another part of the sky.

The Messerschmitts came from the front, bearing down on their lonely prey.

Fogel fired the fixed-turret guns at the front of the plane with no effect. German machine gun fire hit the left inboard engine and scraped away the tire of the left landing gear.

A 20 mm shell slammed against the open waist of the plane, the tail and its underside.

Shrapnel tore into the radio operator's face and chest. Two bullets passed through the fur-covered boot of the other waist gunner, and another bullet ripped the oxygen mask from his face. The tail gunner was blown back into the tail of the plane.

The belly gunner was hit in the face and upper torso and couldn't see from the blood in his eyes.

It didn't matter. All of the plane's guns were out.

The plane dived for extra speed and Fogel skidded across the sky, up and under the flock of American aircraft.

The Germans backed off, but it wasn't over. There were four men wounded, an engine was out and the landing gear had been reduced to a metal stub.

And somehow, Fogel had to land.

Throughout Fogel's war experiences and his stay in Bengazi, Libya, Fogel kept a small diary recording marches, eating grits for the first time, crash-landings in war and training, flying solo through a snowstorm and tangles with the enemy.

The decorated pilot, now blind and partially deaf, flies the U.S. flag in front of his Corpus Christi residence and feels lucky this Memorial Day weekend. He won his wings. None of his crew died on his 54 missions.

And he helped save the world.

May 4, 1943. "Left throttle, right brake! Left throttle, right brake!"

Fogel's wounded plane made a regular approach over the airfield. Col. Compton was in the radio tower watching.

"I radioed I had four men wounded aboard," Fogel said. "They said, 'You land first.' "

With one landing gear gone, the gear might snag on the blacktop and roll the plane into a fiery metallic ball. As the wheels touched down, the left stub dug in and the plane started to veer left.

A voice barked over Fogel's earphones.

"Left throttle, right brake! Left throttle, right brake!"

Fogel gave full throttle to the engine and stood up on the brake with all of his weight.

The swerve stopped and the plane skidded down the runway. At rest, the men went through the top hatch. Fogel had broken his foot and would spend 12 days in the hospital.

But that barking voice saved them, Fogel said.

"I thought it was God telling me, honestly," Fogel said. "But it was Col. Compton telling me. And he saved every person from being hurt."

Dec. 19, 1941. I kissed Mother, Dad, Arlene and Nancy goodbye. I kissed Mother twice.

Two days before leaving Pennsylvania to learn to fly, Ernest Fogel and Betty Jones climbed the brow of a Pennsylvania hill and looked down at the darkness.

On the hill where he had flown kites as a boy he could see the light from the steel mills' blast furnaces down in Rochester, Bridgewater and Freedom.

The Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor, and America was at war.

"What on earth is going to happen to us?" Fogel asked the woman he would spend the rest of his life with.

And Betty "Pete" Jones said, "We just need to pray and stop worrying about it."

After a final home-cooked dinner of chicken croquettes, Pittsburgh potatoes, creamed peas and his mother's special Parkerhouse rolls, Fogel went the next morning to Pittsburgh and found his train.

His family saw him off and he waved until he couldn't see them anymore.

On the train, men had started shooting craps and playing poker. Fogel didn't play. He thought he was too smart to gamble.

Oct. 14, 1942. "Thanks for saving my life."

He learned to fly above the cotton fields and lakes and deserts in Alabama, Arizona and Texas. They started him with biplanes and single-engine aircraft, pushing him toward the B-24 Liberator.

In El Paso he got his first crew, a copilot, navigator, bombardier, engineer, radio operator and three gunners who doubled as assistant engineer, radio operator or armament mechanic.

But on one October Monday, flying copilot on an exercise flight to New Mexico, he saw the responsibility he had for his men.

"On the way back we lost an engine," Fogel's diary reads. "It just quit."

The pilot overshot the runway on his first approach, decided it was too late to go around, changed his mind again and the indecision cost them.

Jerking down, the plane swerved to the left and the wheels collapsed. Shrieking, the bomb bay doors and the bottom of the plane were crushed.

"The plane split open right over my head, and when the plane stopped, I disconnected my parachute harness and seat belt and I went out through that hole above me," Fogel wrote.

But something was wrong. Out on the tarmac, there were only seven men. He still had men missing. Fogel ran back to the plane, which had started to smoke and burn. He crawled through the space where the bomb bay doors had been and yelled.

"Is there anyone in here?" No answer.

He climbed to the escape hatch over the flight deck. One man stood unconscious, holding onto the back of the pilot's seat. Another was struggling up from the floor. Fogel helped slide the dazed man, Greyhosky, off one wing and into the arms of the crew.

Fogel ran back out, and realized one man was still unaccounted for. He and another man again searched the plane but couldn't find him.

The plane was engulfed in fire by then. Fogel went by ambulance to the hospital.

Fogel spent the next few days nursing his back. Two days after the crash he went to Greyhosky's hospital room. The man was in traction. The two said hello.

Then, Greyhosky said, "Thanks for saving my life."

Fogel was surprised.

"Heavens, I didn't save your life," Fogel said. "I just helped pull you out of the plane."

He left feeling embarrassed.

A day or so after the crash, Fogel learned the fate of the missing crewman.

When the plane crashed, the man had been thrown into the bomb bay. As the doors sheared off, the crewman had been dragged along with them. Search crews found the dead man 50 feet from the plane.

Not long after the crash, Fogel headed for Africa and the war.

"And that's how I learned to fly," Fogel said.

Aug. 1, 1943. I got us there and back again and all of us on #51 are all right.

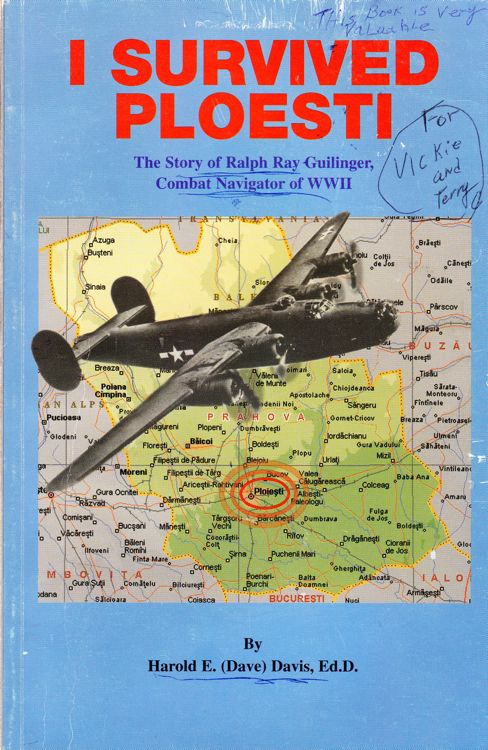

They had their final briefing for the low-level raid on Ploesti, Romania, on Aug. 1, 1943. A successful strike on the oil fields there would be a significant blow against the German war machine.

The B-24s, accustomed to the anonymity of 20,000 feet, would barrel in just 50 feet off the ground for a surprise attack.

It was a volunteer mission. Before it was over, 54 of 177 planes would be shot down and more than 500 airmen killed, captured, or missing.

The men were given maps, money and lists of phrases in several languages in case they had to put down in Europe.

Fogel had his own survival gear: two pairs of socks and GI shoes laced up all the way; a couple of handkerchiefs, a pocket knife, his .45 sidearm, a hunting knife and string.

"I don't know why the string, but I'm taking some," Fogel wrote.

Fogel was assigned a familiar plane called "Let's Go!" hoping it wouldn't.

When he hit the starter he thought, "I hope the son-of-a-bitch doesn't start."

The engines grumbled alive.

Fourteen planes flew out over the Sahara and then crossed the blue barrier over the Mediterranean Sea.

Past the island of Corfu, a routine navigation point, the planes tightened formation and started falling from 14,000 to 6,000 feet, then to a mere 100 feet. Past the Blue Danube, they were three minutes from the initial point, where the planes would turn as one and begin the bomb run.

But confusion because of two identical landmarks caused the group to turn too soon.

Instead of flying toward Ploesti, they were headed toward Bucharest.

A voice came over the radio.

"This is General Ent. Drop your bombs on any military objective."

All planes broke formation and "Let's Go!" turned back toward Ploesti and followed the railroad to a railroad roundhouse, dropping three bombs. The rest of the plane's bombs fell on a railroad bridge.

Fogel turned and met another bomber group head on. Fogel dipped his plane below the already low-flying planes, skipped across the ground and then headed toward the mountains.

It was a Sunday and as they passed back through the country, a few farmers waved at the bomber. The waist gunners saw girls skinny-dipping.

After passing the mountain range, a B-24 got on Fogel's wing. By the time they reached Corfu, seven bombers had joined up.

Fogel's plane taxied in. It hadn't been damaged. The bombers that reached Ploesti destroyed about half the refineries. Fogel would eventually receive the Distinguished Flying Cross for his flight.

But just then, Fogel was too tired to care. He went to the flight surgeon's tent for a shot of booze.

"That was about 14 hours from the time we left until the time we got back," Fogel said.

He escaped the questions of a few war correspondents, went to his tent and stretched out on his cot.

He slept for a long time, his shoes still on his feet.

In a separate narrative, he wrote about the Oct. 19, 1943 mission. Click here to read it.

The website 376bg.org is NOT our site nor is it our endowment fund.

At the 2017 reunion, the board approved the donation of our archives to the Briscoe Center for American History, located on the University of Texas - Austin campus.

Also, the board approved a $5,000 donation to add to Ed Clendenin's $20,000 donation in the memory of his father. Together, these funds begin an endowment for the preservation of the 376 archives.

Donate directly to the 376 Endowment

To read about other endowment donation options, click here.

Reunion

NOTE change in the schedule !!

DATES: Sep 25-28, 2025

CITY:Rapid City, SD

HOTEL: Best Western Ramkota Conference Hotel; 2111 North LaCrosse St., Rapid City, SD 57702; 605-343-8500

Click here to read about the reunion details.