Alfred Goldis - Operations Officer

At one point, I was the Squadron Operations Officer. One of my duties was laying on the mission’s order of battle for the following morning. By the time everyone returned from the movie after dinner, the squadron’s order of battle and time of briefing were posted on the bulletin board mounted on an easel in front of the Squadron Operations tent. All that remained was for everyone scheduled to have an early breakfast and show up at the Group’s briefing. Not everyone was scheduled to fly every mission.

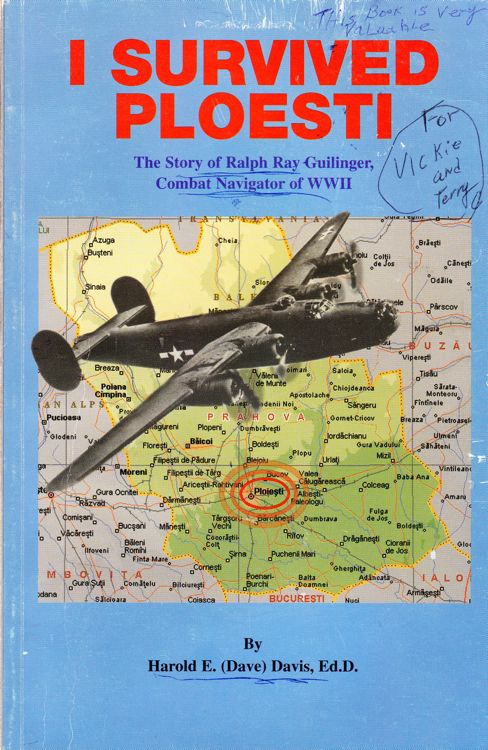

A large well-lit map covered the front wall of the briefing room, on which the Group’s target, rendezvous and initial points to target were clearly illustrated with pins connected by strings of black thread. Briefing consisted of where our group’s position was in the order of battle; current weather conditions to and over and around the target; and on-site intelligence data transmitted by our operatives describing the German airfields and anti-aircraft defenses near the target. Neither weather nor on-site data, while helpful, could be relied on as gospel. So, there were always secondary targets named in case the primary target was obscured by cloud cover. As lead pilot, I was responsible for choosing a secondary target if the primary target was inaccessible.

After Q. & A., we rode out to the flight line, found the revetment with our assigned plane, checked our gear, and climbed aboard. The chocks were removed by the ground crew and after a thumbs-up by the ground crew chief, we were ready to start and warm up the engines while trundling out to the flight line observing the order of battle on the way. Since I was restricted to lead ship flying, I was usually first in line. A green flare from the control tower was the signal to start down the runway. The others followed in very short intervals; one just lifting off, with another half way and a third starting down the runway. One wide, lazy 360° climbing left turn resulted in the entire group properly positioned for a fly-over of the field on our first heading to rendezvous where other groups in the wing arriving at their briefed times would take up their assigned positions in the formation. After another 360° climbing turn, if needed, the entire wing would climb to the briefed altitude on the way to the target’s initial point. The climb to altitude at roughly 1,000’/minute took about twenty five to thirty minutes.

If the target was beyond the Alps, we would have fighter cover up to the foothills at which point the fighters would break off and return to base for re-fueling. They would meet us on our return trip and escort us home. By that time, any damage or losses due to enemy fighters and anti-aircraft fire would have been done. A squadron of Tuskegee fighter pilots sometimes provided our cover. We never lost a plane when covered by the Tuskegees. Those guys were flyin’ fools and would successfully engage any Luftwaffe fighters that came anywhere near us. A squadron of Nisei were also excellent and flew as though they had a point to prove.

Once the bombs were dropped, we made note of the results in our log books which were verified by aerial photographs of the target area. Good, sharp pictures were worth a thousand words during de-briefing. We would also make note of planes shot down by AA fire and/or fighter attack. It was important to record where and when the losses occurred. Key information was the number of parachutes that opened. With luck, there would be ten per downed plane. But this was rare. Crewmen were often too badly wounded to bail out.

Whenever possible, fellow crewmen would dress any open wounds using sulfalinomide powder and other drugs covered by sterile bandages from the medical kits. There was one such kit per man and each contained one morphine syrette for extreme pain. Canteen drinking water was essential except for belly wounds. If the pilot was able to get the crippled plane back to base he would notify the tower that there were wounded aboard and request permission to come straight in and land quickly so that ambulances and doctors would be immediately on hand at the end of the runway. Whenever the pilot was wounded himself, the co-pilot would take over, while the pilot cared for his own wounds. More easily said than done as any hit to the flight deck would most likely be severely damaging with little time to maneuver. Just the same, many a crewman and plane were saved by the quick thinking of the pilots and crews.

The rest of the formation flew back intact gradually losing altitude until oxygen masks could be removed at 12,000’. As the formation approached home base and entered the traffic pattern at roughly 1,500’ losing altitude at about 500’ per minute, the lead ship would signal for an echelon formation as it turned on final approach with wheels still up. As the lead ship’s nose came very close to the start of the runway, the lead pilot would execute a tight, climbing chandelle, drop wheels at the top of the turn, and every other plane would peel off behind him and follow suit in quick succession. It could be dangerous if not executed properly. And the result was a plane landing every 15 seconds or less. The maneuver was done to give the ground crewmen a morale boost since they were always very anxious to know if their particular planes and crews got home safely. It was important for them because it meant that their planes had been well-maintained.

The website 376bg.org is NOT our site nor is it our endowment fund.

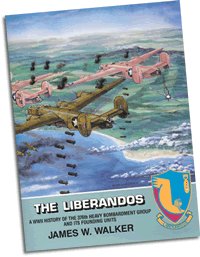

At the 2017 reunion, the board approved the donation of our archives to the Briscoe Center for American History, located on the University of Texas - Austin campus.

Also, the board approved a $5,000 donation to add to Ed Clendenin's $20,000 donation in the memory of his father. Together, these funds begin an endowment for the preservation of the 376 archives.

Donate directly to the 376 Endowment

To read about other endowment donation options, click here.

Reunion

NOTE change in the schedule !!

DATES: Sep 25-28, 2025

CITY:Rapid City, SD

HOTEL: Best Western Ramkota Conference Hotel; 2111 North LaCrosse St., Rapid City, SD 57702; 605-343-8500

Click here to read about the reunion details.