Benjamin J. Haller, Jr. Mission February 7, 1945

GOD WAS AGAIN WATCHING OVER US

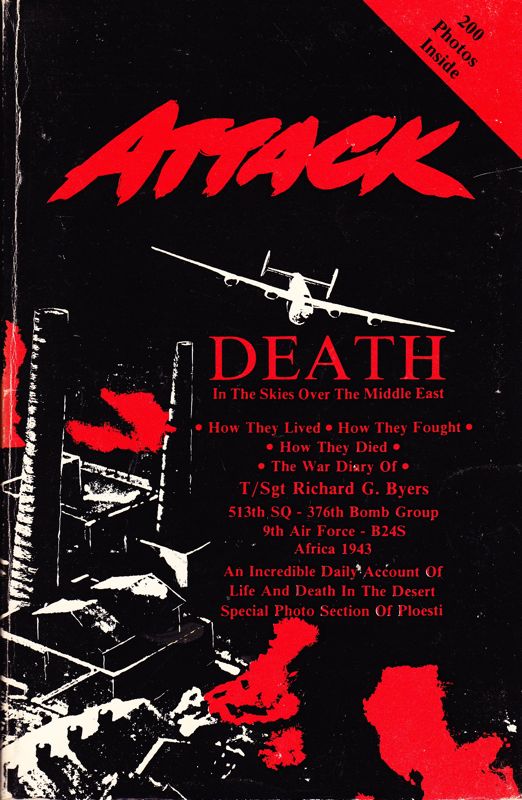

I was the 2nd Lt. Bombardier on the crew of 2nd Lt. Joe Ballinger, who was my roommate from the time our crew was formed at Davis-Monthan Field in Tucson, AZ, until the end of WWII in Europe when we flew a B-24 home from Italy. We were part of the 514th Squadron of the 376th Bomb Group.

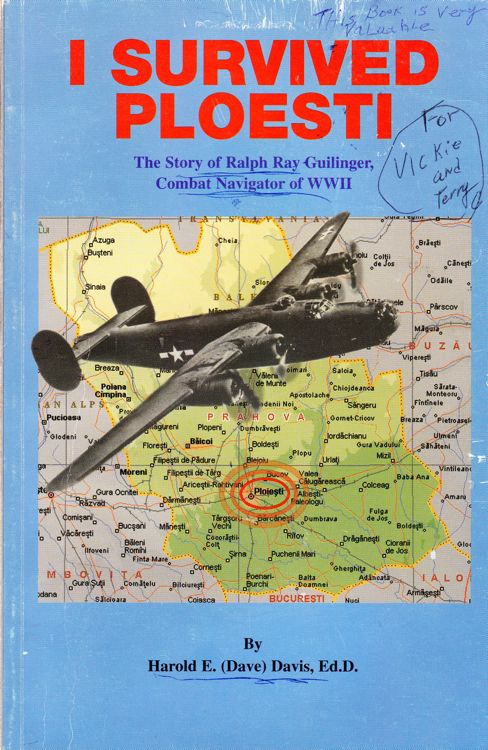

On 2/7/45 our mission was to hit the Moosbierbaum Oil Refinery on the Danube at Vienna. It was the last major oil refinery available to the Germans and was a crucial target to cut off the enemy's fuel supply for its field forces. Our co-pilot that day was Fred Stangl, a 1st Pilot checking out with us on his first mission. As we began our bomb run at 26,000 feet the flak was solid, a continuing blast of bursts across our line of flight, since the flak gunners had been able to enter the altitude and direction of the squadrons in front of us, so by the time we arrived, they were zeroed in.

As these ear-shattering bursts kept exploding, we kept turning into them to get set on our bomb run, but my body kept turning to the right! As the wave of flak bursts engulfed our Squadron we could feel the great number of hits as pieces of flak pierced the fuselage. As we squared away on the last segment of our run we had two hits directly in front of our plane-one blast hit the oil lines of #4 engine, spewing black smoke in a billowing cloud from that engine. The same burst or a companion one hit # I engine, blowing off the governor so it was impossible for Joe, our pilot, to maintain its rpm control. That flak curtain sent one piece hurtling through the windshield and hit co-pilot Fred Stangl on his forehead. Thank God his helmet was firmly in place. He was stunned for a couple of minutes then helped Joe battle for control of our plane.

I can recall vividly that my first thought when we knew we were hit bad was, "What's going to happen to Peggy and our baby?" It was just 19 days shy of our first wedding anniversary and she was at home in Omaha six months pregnant. The flak kept hitting our plane and my next recollection was praying, "God, I don't have time to pray. Whatever I've done up until now is going to have to count."

The next blast hit in the middle of our seven planes just as we were ready to call "Bombs Away!" We took a direct hit through the leading edge of the left wing between #1 and #2 engines ... but it didn't explode! That hit threw us upward so that I was looking into the eyes of the tail gunner about 10 feet in front of us, then the ship fell back in formation. At about this time, our photographer, Staff Sgt (lst name?) Carter, had just leaned over to the left side of the plane to turn on the intervalometer when he was hit on the inside of his upper left thigh by a large piece of flak. It was a good thing he was bending over sideways instead of kneeling straight up over the camera! I dropped our bombs with the rest of the 514th and when the bombs couldn't have been more than 50 feet below our plane we took another direct hit on the underside of the bomb bay catwalk. That explosion bent the catwalk upward but that steel beam saved our lives by deflecting most of the flak downward.

The shell that went through the left wing apparently was a dud, but it cut all the left wing gasoline lines, so liquid and vaporizing gas was streaming back through the bomb bay doors that were still open and filling the bay with gas fumes. As soon as "Bombs away!" was called, we fell out of formation, with #4 apparently on fire, #1 heavily damaged, and #2 feathered and out of gas. (Two other 514th planes went down at the same time and we learned later that all 20 of those men bailed out or landed safely and were taken prisoners. Unbelievably, with all that damage to three B-24s, not a man was killed!)

After bombs away I made my way through the bomb bay with its heavy spray of gas and fumes to the waist gun area where I gave the photographer First Aid. Al Roliman, our waist gunner had tried to help the young guy but had pulled his oxygen hose loose and was losing consciousness. Byron "Red" Brought, our tail gunner was out of his turret, as was Clyde Starr, our ball gunner, trying to help those two. We got Al reconnected to his oxygen hose, patched up the photographer and I started forward again through the bomb bay. The doors were open because we were dumping everything we could lay our hands on - ammo belts, loose equipment, etc. The plane gave a bad lurch at that point because of #1 and I was hooked on a bomb rack. I was hanging partially over the open doors, trying to get upward pressure with my fingers to release the harness from that hook when a second lurch tore me free and sent me headfirst the rest of the way across the catwalk into the chest of Navigator Bob Kaufhold, who was braced against the underside of the flight deck. I made sure Don Buck was out of the nose turret, then got up on the flight deck.

Joe and Fred meanwhile were fighting a losing battle trying to maintain control of our plane. We were only a few minutes away from heading east to land behind Russian lines but we opted to take our chances heading south. With only one and a half engines left, we kept going down steadily, trailed by black oil smoke and the white stream of gasoline vaporizing. Three P-51 s from our fighter cover had been assigned to stay with us as we went through cloud cover about 7,000 feet and losing altitude steadily. When we disappeared under the clouds the remainder of the 514th headed home to San Pancrazio, and reported we were all apparently lost, since no chutes were seen coming out of our plane.

All of that bomb run and its aftermath seemed to be one flashing moment, but in reality Joe and Fred were able to keep us airborne from about 12:28 noon target time until 1 :00 p.m. when we found ourselves at a low level over the mountains in northern Yugoslavia. When #1 engine eventually gave out completely, Joe signaled to stand by for "bailout" at 2,000 feet. While we were getting everyone ready to abandon ship over what looked like mountain tops, trees, boulders and gullies, there was one final lurch and #3 quit without warning, so all four engines were now gone.

At that moment we looked out and there a short distance ahead of us, God had placed a small, snow covered farm field ... but was it within reach of a powerless heavy B-24? That's when Joe and Fred performed a miracle, with some genuine prayerful help from the rest of us.

The old saying that a B-24 glides like a streamlined brick wasn't quite true. Joe kept the nose up as much as he could to maintain altitude, and still maintaining enough air speed to keep control. We could see it was a small field and our line of approach was to a bordering group of trees, a snow covered field and a small, centuries old brick farmhouse at the other side of that short field. We hit the tops of the trees and could hear the branches ripping inside the open bomb bay. Joe and Fred got it down on the snow, then with a violent jerk we realized the left landing gear bad been ripped out up into the roots of the wing.

It was then when we found out what a superb pilot we had been blessed with. Joe, with all the strength he and Fred could apply, held that left wing tip up off the ground as we skidded through 15" of snow with mud underneath, headed straight for that farm house. Joe judged the distance and drag perfectly and at the last minute when I thought we couldn't miss the house, he eased the left wing tip into the snow, applied the last brake power left in the right gear and the plane skewed sharply to the left. Then, with a mammoth jerk the nose wheel snapped off and shot all of us forward from our crash positions. However, Joe had gotten the plane slowed down enough that instantly all we could hear was dead silence. Then, in record breaking time all 11 guys evacuated poor old #74.

We couldn't believe we had all lived through that nightmare. But we knew we were in enemy territory and had to act fast. The first thing we did was to stand in a row several feet apart and wave our arms so the P-51 pilots could fly over at 50 feet and count how many had gotten out of the plane. After three passes they had radioed 15th Air Force at Bari of our position, then took off for home, probably low on gas. The second thing we did was retrieve our A-3 flight bags each man had carried aboard, for they held our combat boots, extra changes of clothing and as many Krations as we could scrounge from the air base to build a small hoard of food. After getting everything out, we counted 163 holes in our plane, including the one that didn't explode. Bob Kaufhold had a small camera with him and took pictures of the entire scene.

We could see a small river about 400 yards north so we finally decided we should try to cross the ice and hide in the woods on the far side. At the moment I v was ready to fire my .45 into the gasolinecovered wreckage after destroying the Norden bombsight and aerial camera film, a couple of older women, a real old man with a cane and a couple of small children appeared outside the farm house watching us. I pulled out my American flag arm band, waved it at them and yelled, "Amerikanski!" They laughed, waved back and came running with the shout, "Partisane, Partisane!" God was again watching over us. They took us into their small farm home where we waited for nightfall, since they told us through signaling, and pointing to Slavic words in our escape dictionary, that help was coming.

That night when it was pitch dark the front door burst open without warning! We all jumped and I pulled out my .45, the only one who had a sidearm. It was a giant of a guy grinning from ear to ear and his first words in English were: "Hi, boys! My name is Ivan Antoncic. I'm from McKeesport, Pa.!" Our tail gunner, Red Brought, jumped up, introduced himself and said, ''I'm from Harrisburg, Pa.!" From that point on we were in friendly Partisan hands. John (or Ivan) had lived in the U.S. for nine or 1 0 years to earn enough money to return to Croatia to marry his childhood sweetheart, then return to the states. The war broke out before they could get out, so John and his wife were Allied spies through the rest of the war.

From that point on we walked up and down mountains and through forest paths, moving in and out of three villages - Cazma, St. Stefanje and Grabonica - over the next four weeks. Although the village peasant farmers were destitute, they shared what little they had with us. The Germans had confiscated every bit of livestock, fowl and other food, so the Croatian people had practically nothing except the remaining grain in their fields. We learned from John that we had landed 400 yards inside a newly captured three-mile wide by four mile long area controlled now by Tito's Partisans.

The Germans knew where we were but were so busy trying to evacuate the Yugoslav peninsula at that point in 1945 that they made no effort to come after us. They did send a small plane every three or four days to drop 100 pound bombs on wherever they thought we were staying.

We were told those bombs were makeshift ones filled with concrete, metal scraps and only a little powder to make them detonate, since good shells were being saved for more important action.

Since it was February in the Alps there was plenty of snow and cold. At the third village (Cazma) we met a small contingent of British Intelligence personnel whose job was to keep headquarters in Italy informed of German movements, and especially to trace on a daily basis the westward movement of Russian troops. The head of that small unit was Major Allen, who was either British or Canadian, I've forgotten. He was joined by an assistant, a Captain Phyfe, from Britain, and four British radio sergeants. Their British mission and others like it in Yugoslavia had been secretly set up by a master British Spy named Brigadier Maclean, whom I met some years later here in Des Moines, who gave me an autographed copy of his memoirs written after WWII recounting his Majesty's service from the time he entered it in World War I!

The native population and the Partisans treated us kindly. We experienced daily what it meant to share, and finally we learned that C-47s would be landing on a small field near our last village to pick us up. "Us" by that time consisted of the 11 men on our crew, four other American airmen from another B-24 nearby crash, seven British POWs (who had escaped from a German prison camp at Klagenfurt, Austria, in January after having been in prison since the fall of Athens, Greece in September, 1941) and a 19-year old British pilot who had bailed out of a lend-lease P-51.

Although it was the season for violent mountain storms there, the weather had miraculously cleared that month. We were not allowed to be seen in open ground so the German planes couldn't spot us. However, the elderly men and women of the village went out daily, hooked up big logs with chains to a few oxen they had hidden in the woods, and day after day dragged snow off the field. Then they held long, heavy branches sharpened at the end and dragged them under their arms at a diagonal to the field to let the melting snow run off. Finally, the field had been cleared enough that Major Allen announced two C-47s would pick us up. However, the Germans got wind of this and came over that afternoon and dropped a string of genuine 100-pounders that left several craters in the line of takeoff. Without batting an eye the old men and women and a few Partisan soldiers dragged in fill dirt, stamped it down as much as possible and called for the planes the next day.

The next morning, which was March 2nd or 3rd, the American built C-47s, on lend-lease to the British Royal Air Force and flown by South African crews, landed to rescue our motley assortment of castaways. The pilots divided the 23 of us as evenly as they could by weight between the two planes. The planes were bogged down in the mud with the extra weight and the first one was stuck in the mud of a bomb crater. Without hesitation the old men and women got under the wings, heaved up with their backs or pushed up with their hands while the pilot revved up to pull forward. As the plane broke loose and gained speed, they fell to the ground until the plane was moving freely, then got up and came back for our plane. We were astounded at this final display of "hospitality." Our plane got off without a hitch; then, as we raced over the treetops just beyond the range of that field, we could hear and feel the ping, ping of rifle fire. The damned Germans just couldn't let us go without a farewell!

We returned to 15th headquarters at Bari, where we were deloused, debriefed, and re-outfitted with new clothing. At S- 2 interrogation, I relayed the information the British soldiers had given me, along with a crude map they had drawn, showing that the Germans had made a giant ammo storage out of a Catholic church in Klagenfurt, thinking no one would touch it. r was told a mission would be scheduled in a day or two to let the Germans know otherwise. Glad I wasn't on it.

I bet the men on our crew that when the plane from the 514th came over to pick us up the last day in Bari that it would be flown by our Squadron CO., Lt. Col. Henry "Hank" Taylor. I won the bet. As we watched the crew climb out, the first man we spotted was Col. Taylor, who warmly greeted each of us. From that point on we were back home at the 376th and back to work flying B-24s again

The website 376bg.org is NOT our site nor is it our endowment fund.

At the 2017 reunion, the board approved the donation of our archives to the Briscoe Center for American History, located on the University of Texas - Austin campus.

Also, the board approved a $5,000 donation to add to Ed Clendenin's $20,000 donation in the memory of his father. Together, these funds begin an endowment for the preservation of the 376 archives.

Donate directly to the 376 Endowment

To read about other endowment donation options, click here.

Reunion

NOTE change in the schedule !!

DATES: Sep 25-28, 2025

CITY:Rapid City, SD

HOTEL: Best Western Ramkota Conference Hotel; 2111 North LaCrosse St., Rapid City, SD 57702; 605-343-8500

Click here to read about the reunion details.