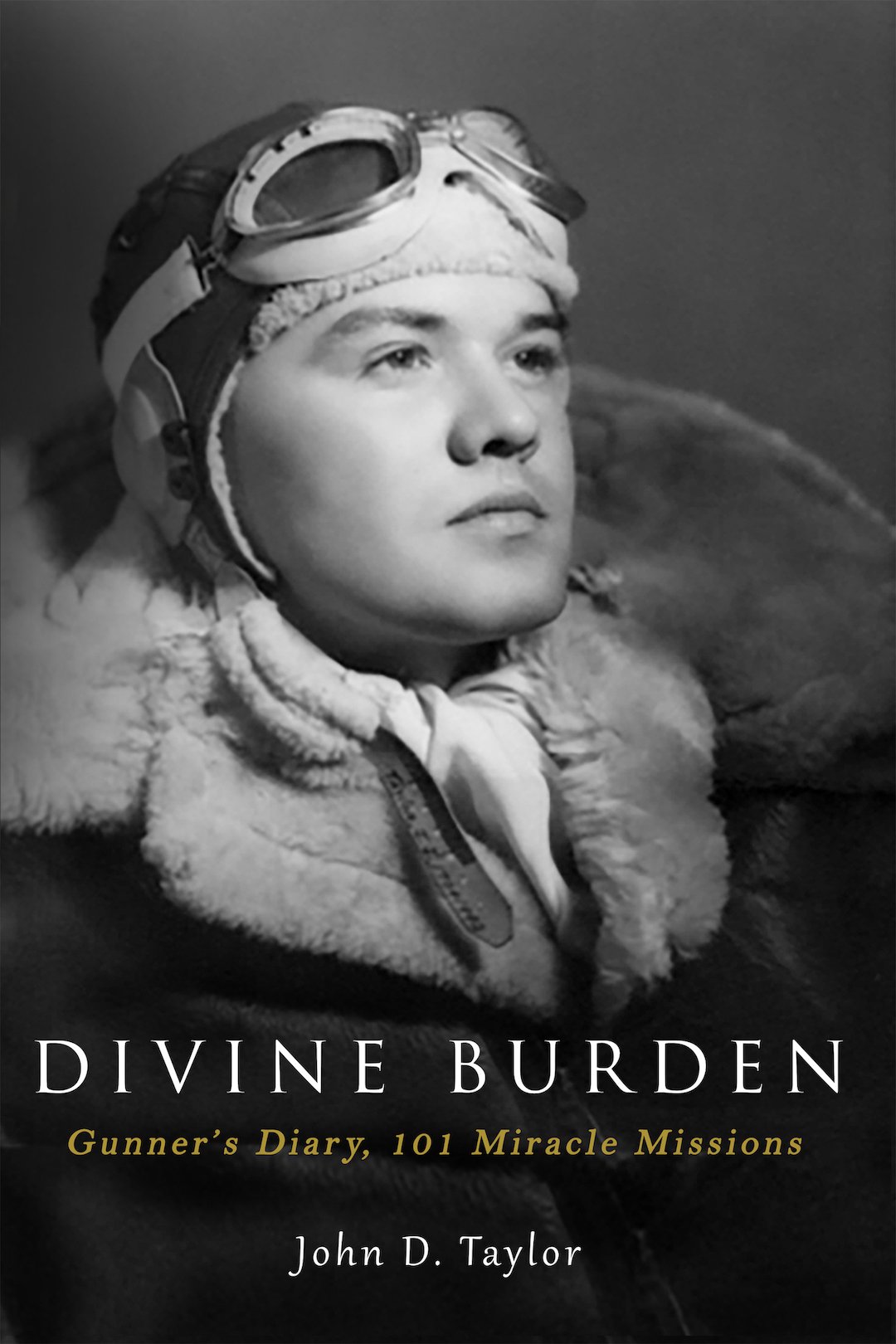

Dean O. Holman

Dean Holman was the gunner on the Eugene Thurman crew. On the February 23, 1944 mission to Steyr, he was a substitute gunner on the Henry Gibbons crew. The plane was shot down and he became a POW.

The following his recounting of his overseas assignment.

Training and Combat Experience of Dean O. Holman 36-432-660

Written May 30, 1996

Edited July 23, 1996

I left Monticello, Illinois, November 4, 1942, and went to Scott Field, Belleville, Illinois . I was sent to Keesler Field, Biloxi, Mississippi, for indoctrination exams and basic training. The exams showed I should either go into mechanics or machinists training. But I didn't get much basic training. I was only there two or three weeks. They cut my basic training short because they needed to fill a new class of mechanics. So I was shipped out to Lincoln, Nebraska , where I started Airplane Mechanics (A.M.) School. Near the end of the classes they asked for volunteers for gunnery school. I think that was the only time I volunteered while I was in service. I was accepted but I had to have my tonsils removed. I went to the hospital at the end of one class, since we could miss three days and still stay with the group we were with. I was in the hospital three days before anyone did anything, and another week after the surgery.

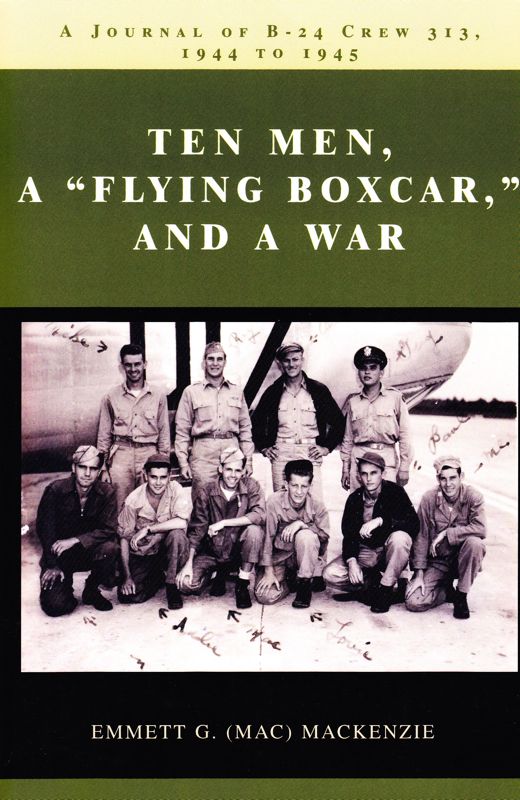

We were sent to Ft. Myers , Florida , in April, 1943, to start gunnery school. When we finished gunnery school we went to Salt Lake City, Utah , where I was assigned to a flight crew in Pocatello, Idaho. When I got there I was assigned to a crew as 2nd Engineer of a B-24 bomber. The crew of a B-24 was made up of either ten or eleven men. In combat, if there were enough men, the First Engineer was relieved of firing the top turret so he could be free to assist the pilot, copilot, or radio operator. The eleventh man fired the top turret. Up front were the pilot, copilot, navigator, bombardier (the four officers), the first engineer who took to top turret, radio operator, and nose turret gunner. In the back were two waist gunners, the ball turret gunner, and the tail gunner.

Bill Denton and I were the first men assigned to be part of our crew. In a short time eight more men were also assigned to our crew and we started flight training. Our first pilot had an attack of appendicitis while we were on a training flight. The copilot, Lieutenant George Jensen, landed the plane with the 1st Engineer, Staff Sergeant Milton Hewitt, as copilot. This was the first time either of them had landed a B-24 at these positions. We landed a lot faster than usual, but otherwise it was very good landing.

Several weeks later our second pilot got very sick while we were in the air. This time our copilot was not with us. A major was flying copilot to get in some flying hours. He took over as pilot and the 1st Engineer was copilot again. The major had not landed a B-24 but two or three times, but he did all right.

We were assigned our third pilot, Lieutenant Eugene Thurman. He was a very good pilot and leader for our crew. Things went great until one day the tail gunner found a small piece of metal and brought it into the barracks. He asked some of the boys if they knew what it was. They were playing cards and didn't pay much attention to him. He sat down on the next bunk and was poking at it. It exploded and blew the ends off several of his fingers. The piece of metal was a detonator cap for setting off explosives.

The rest of our training went well, other than flying at 10,000 feet without oxygen during a formation training flight. During training we didn't have any particular aircraft that we flew regularly. The altimeter on the plane we had this day was not working right, so we didn't realize that we were flying high enough to need oxygen. We didn't report it for fear of being grounded for some time. The next few days we had a lot of aching joints, but no serious effects.

After we finished our training our crew was sent to Topeka , Kansas , to get a new B-24 bomber to fly overseas. We were there a week or ten days when our plane arrived. We had all our belongings loaded on the plane but our take off time was delayed twenty hours. The crew had to stand guard at the plane. Our pilot, Lieutenant Thurman, had us draw for two-hour shifts. He and the other three officers, the copilot, navigator, and bombardier, took their turns. The pilot said we were a ten-man crew and if the crew only had a dollar it was ten cents each. That is the way our crew always worked.

We flew from Topeka, Kansas, to Puerto Rico and stayed the night there. From there we went to British Guiana, South America . The next day we left for Belem , Brazil . During this flight the pilot said his compass showed we were going north, not south. The navigator, Lieutenant Walter McKay, used his astrocompass and told the pilot the right course. We came in right over the runway in Belem . We were there a week before getting the plane's compass repaired.

Our next stop was Dakar, Senegal, Africa . This was a long flight with little room for error or we would run out of fuel. We didn't have much left when we got there. The next day we flew to Casablanca, Morocco. We stayed there a few days. Our next stop was Algiers. We were given the wrong code, so they weren't going to let us land alone. They were going to send fighter planes up to escort us down. The Germans were jamming the radio which made it even harder for our radio operator, Sergeant Joe Rosendale, to communicate with the tower. Finally he was able to get the right code, so they let us land.

The next day we landed in Sicily . Most of the crew was playing cards but the bombardier, Lieutenant Sinico, and I wanted to do something else. There was no officers' club there but there was a place for enlisted men. I told Lieutenant Sinico that if he would take off his Lieutenant's bars and his hat, he could get in with me. He put them in his pocket and we spent a couple of hours together with the enlisted men. When all the sports equipment that was reserved for the enlisted men was checked out, our officers would check out theirs for us to use.

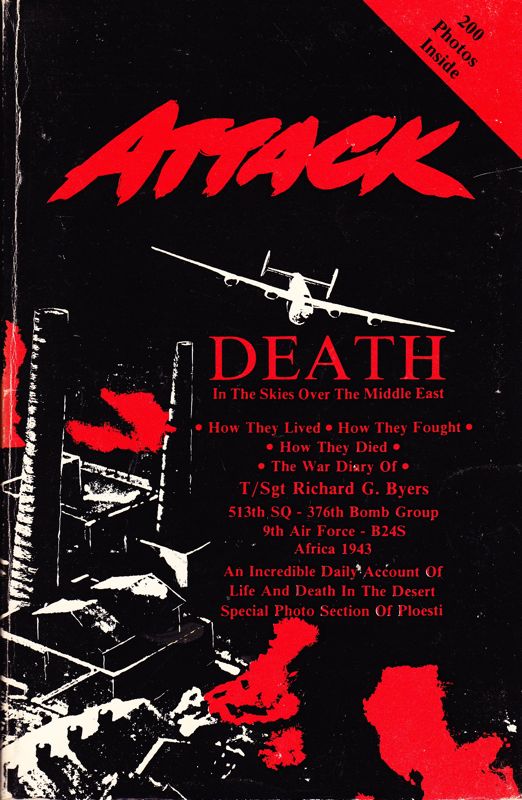

Our next stop was the 513th Bomb Squadron with the 376th Bomb Group at an air base near Brindisi, Italy . Our crew stayed at the 376th, but they gave our plane to another group. So we flew whatever was available. Lieutenant Thurman, our pilot, flew as copilot with another crew his first mission on December 6, 1943. We were all supposed to fly our first mission with another crew. But they were short on crews, so on December 7, 1943, our crew flew our first mission together over Athens, Greece. That was the first time I heard anti-aircraft shells explode. We were to turn left after dropping our bombs, and I was to hold a camera out the window to take pictures of the target. They didn't turn sharp enough, so I couldn't find the target. I kept leaning out until the wind blew my steel helmet off. The other waist gunner, Keith Denton, took hold of my feet. He was afraid I would fall out. That was the only steel helmet I ever had.

Click here to read about the December 19, 1943 mission.

A short time later the base sent a plane to look for us. We fired

several flares so they could see us. We also laid down in the field so

they would know someone was injured. They had trouble finding an opening

in the rock wall large enough to get the medical and rescue equipment

to us. Before they arrived I crawled around the bombs to see if I could

get to Philip's feet, but I couldn't get to them.

One doctor

thought they would have to cut his feet off to get him out. They had to

be especially careful because of the leaking gasoline. But they started

tearing the airplane apart. While they were working we heard a hissing

sound that we thought was a bomb about to go off. We all started to run.

The pilot had an injured leg but he still ran over me. Turned out it

was a leaking oxigen tank. Around 10:00 PM they made the rest of us

return to the base. They got him out about two hours later, about eight

hours after we crashed. They saved Philip's feet, but he had a lot of

trouble and pain the rest of his life. Years later, while visiting

Philip and his wife, Sally, he told us that back home the morning after

the crash their 3-year-old daughter woke up and told her mother, "Daddy

went boom."

A short time after that crash the nine of us--all of

our crew except Dickey, who was in the hospital--was to go to the Isle

of Capri for a week of rest leave. They put about twenty men on a B-24

to fly us to Naples , Italy . The plane only got about 500 feet off the

ground and wouldn't go any higher, so we landed and got on another

plane. We all enjoyed the week of leave. But even after the leave our

tail gunner, Art Nustad, was still afraid to fly. He quit flying and was

assigned other duties.

After returning from rest leave we flew

ten more missions. I think they were mostly over Yugoslavia . I had not

flown over Germany until February 22, 1944 , when we went to Regensburg ,

Germany . We returned without much trouble. The heater in the cockpit

quit working and our pilot, Lieutenant Thurman's feet were frostbitten.

So our crew was not supposed to fly the next day.

At 4:00 the

next morning they woke me and said I was to fly with another crew. One

of their crew was sick (drank too much the night before). The pilot of

that crew was Captain Henry B. Gibbons from Ft. Worth , Texas , and the

copilot was Second Lieutenant Michael J. Solow from Grand Rapids ,

Michigan . Keith Denton, our other (right) waist gunner, flew with

another crew that day, too.

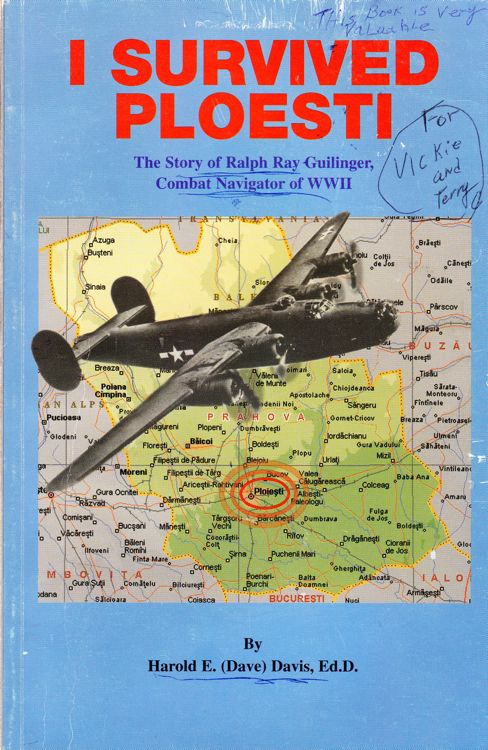

We were going to Styer, Austria , to

bomb a ball bearing factory. Before we got there we encountered a lot of

German fighter planes, Messerschmidt 109s. All the fighters I saw were

Goring Yellow Noses. I was hit in the left ankle, which was broken, and

had several shrapnel wounds. Whenever we encountered enemy fire we had

flack vests we put on. They snapped at each shoulder. The snaps were so

high on the shoulder that we couldn't snap them ourselves. The other

waist gunner couldn't get one of mine snapped. So my flack vest must

have fallen off in the fracas. I don't remember ever taking it off. I

wouldn't have gotten as many shrapnel wounds in my chest and back if it

had been in place.

Two of the other gunners were also hit. It was

customary for the pilot to give the order to bail out, but the intercom

was out to the front of the plane. The pilot and copilot may not have

been able to give us the order to bail out even if the intercom had been

working. After we got home we found out that the pilot and copilot were

the only ones killed in our crew that day. It seems they died from

enemy fire while the plane was still in the air.

When we saw the

plane was on fire we made the decision on our own that it was time to

bail out. The place to bail out of a B-24 was a hole in the floor, not

an opening in the wall like we often picture. We were trained to sit at

the hole with our feet hanging, then jump out feet first. The first guy

was sitting at the hole hesitating to jump. But the second guy was ready

and anxious to get out of the burning plane. So he shoved the first guy

out.

I had trouble getting my parachute on, so I was the last

one of the four men at the back of the plane to get out. The first aid

kit that was on the parachute harness had slipped down and was in the

way to snap the parachute on my chest. I finally got it. I didn't take

the time to unhook my oxygen mask and intercom. My injured left ankle

hurt enough that I was hopping around on one leg. I didn't want to try

to maneuver around to sit down at the hole to bail out, so I just dove

through the hole head first.

We attached our parachute to a

harness on our chest. So we were trained to lean back when we pulled the

rip cord. Otherwise the shroud lines could cut your face all up as they

were yanked out by the parachute. Apparently I did that okay. I didn't

have any trouble with the shroud lines.

A lot of planes were shot

down and a lot a parachutes were in the air. A German fighter flew by

me and the pilot waved at me. I waved back. It was no time not to be

sociable. Glad he didn't shoot.

We were trained to bend our legs

when we landed. I was especially careful to bend my left leg. I sure

didn't want to land on it. I made a pretty good landing. I landed

several yards from a farmhouse. Four older men picked me up and took me

to the farm house. Later a German soldier came to the house and they

gave me first aid. The navigator of the crew I was with was in the same

farm house. They put us in a bobsled pulled by two horses and took us to

an ambulance waiting on a road. There was several inches of snow on the

ground.

That is the last I remember until I woke up the next

morning in a hospital room in Wels, Austria, with a cast on my leg and

several bandages. I got gangrene in my leg and a week later an Austrian

doctor, Dr. Mussman (pronounced MOOSE muhn), amputated my leg below the

knee. In the bed next to me was Morris Ruttenburg, the tail gunner of

the crew I was flying with. He had been shot in the right ankle. Two

other Americans were in the room--Joe Fritsche from Sacramento ,

California , and Lieutenant Kendall Mork from North Dakota . We spent

the next three months in those beds in that room, and the following

eight months in a prisoner of war hospital.

To read further about the Feb 23, 1944 mission and his time as a POW, click here.

The website 376bg.org is NOT our site nor is it our endowment fund.

At the 2017 reunion, the board approved the donation of our archives to the Briscoe Center for American History, located on the University of Texas - Austin campus.

Also, the board approved a $5,000 donation to add to Ed Clendenin's $20,000 donation in the memory of his father. Together, these funds begin an endowment for the preservation of the 376 archives.

Donate directly to the 376 Endowment

To read about other endowment donation options, click here.

Reunion

NOTE change in the schedule !!

DATES: Sep 25-28, 2025

CITY:Rapid City, SD

HOTEL: Best Western Ramkota Conference Hotel; 2111 North LaCrosse St., Rapid City, SD 57702; 605-343-8500

Click here to read about the reunion details.