Wilbur Mayhew Mission January 31, 1943

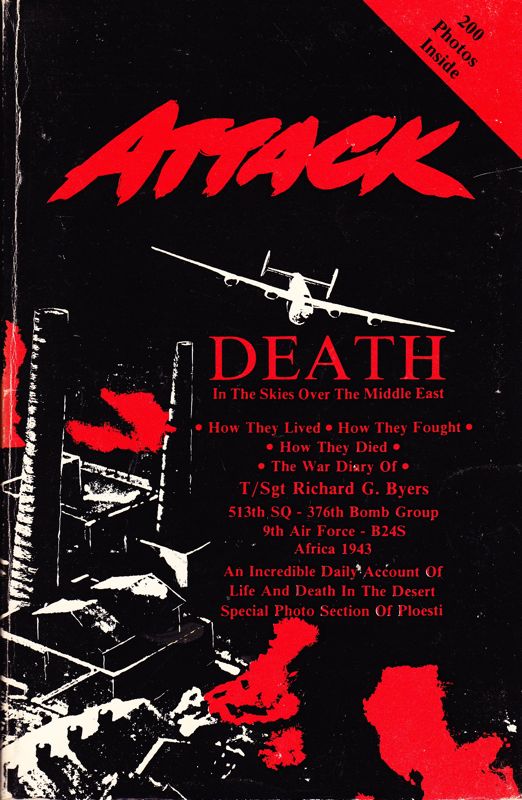

Major Fennel had returned to the U.S.A., so Capt. Bill (Jumbo) Stewart was our pilot on this flight. We took life rather easy for the next three or four days. Then we were scheduled to go out again. The weather was bad for about a week, so we weren1t able to go. Finally, on January 31, 1943, we took off for Tobruk about 4 A.M. (ALWAYS 4 A.M.). We had been hearing rumors about returning to the States for a couple of weeks, so every day we expected to be relieved. Naturally with the thought that we were going home shortly, we weren’t very anxious to go on this raid. For some reason, our entire crew had a funny feeling when we took off that morning. Joe Taulbee, our regular bombardier, was to fly in the lead plane with Major Toomey that day. As we were flying the last position in the “Purple Heart” element, we had a man that had never been on a raid before as our bombardier. This didn1t make us feel any better" because this was the first time our crew had ever hit a target with the crew broken up. We reached Tobruk about 8 A.M. and spent the morning getting the plane in readiness for the impending mission. We took off about 1 P.M. headed for Messina, Sicily. As we started across the toe of Italy, I had a feeling that all was not well, but I couldn1t put my finger on the reason. Everything was calm and peaceful as we crossed the northern coast of the toe of Italy and turned south towards the straits of Messina. As soon as we turned though, everything changed completely. The guns on the coast of Italy, as well as on Sicily, and the warships in the harbor of Messina seemed to turn that part of the sky into a solid wall of flying steel. I looked above, and it seemed as though it could rain from the clouds of smoke from the exploding “ack-ack” shells. There was another layer of black smoke about 1,000 feet below us and a third layer about as thick on our own level. To make matters worse, our tail guns had frozen while we were over Italy, and now one of our superchargers burned out causing us to straggle behind the rest of the formation. Before any of us were able to drop our bombs, the lead plane received a direct hit by anti-aircraft fire in the left wing knocking one engine into the sea, as well as the left landing gear, and putting the second engine out of commission. About the same time, #2 & #4 engines on our plane were set on fire, our oxygen system was cut, our hydraulic system was cut, and the right tire was punctured. In addition, the upper turret and tail turret were hit and damaged. Even before we were out of the flak, the fighters closed in for the kill. They knocked out the third engine on the lead ship, and it crashed in the sea about 20 miles off the coast of Sicily. The entire crew was killed.

With two engines on fire, our plane began to straggle even farther behind the other eight planes of our formation, the German fighters thought they had us dead to rights. For that matter, we figured they did too. With no oxygen at 23,000 feet and two engines on fire, we began to wish we were back home in bed. We tried to get our parachutes on by this time, but fighter attacks came so frequently we were unable to do so. On the first fighter pass, the German airmen learned our tail guns were out, so the next three attacks came on the tail. Pat stayed in the turret and tried to get it operating again, but it just wasn’t any use. One Messerschmitt 109, came in on the tail and put three cannon shells through the left side of the turret. The next ME '109' blew the plexiglass off the top of the turret. The next one shattered the bullet-proof glass in front of Pat. That was enough, even for Pat, so he climbed out of the turret and walked the six feet or so up to the waist guns that Mac and I were operating. By this time, we had started into a dive to get down where we could breathe without oxygen and also try to extinguish the fires in the engines. I guess that dive was all that saved us because we were diving past the "rest of the formation when another ME 109 closed in on our tail for the kill. This “Jerry” opened up with his cannon and machine guns at about 400 yards; and he attacked in such a manner that no one in our plane could shoot back at him. Holes began to appear all over the ship, and smoke from his cannon shells seemed to fill the ship. Pat dropped as though someone had slugged him, Mac jumped suddenly and I felt something hit me in the leg like someone had thrown a dart at my leg from about six feet. It is strange what thoughts pass through a fellow’s mind at such a time. I had been expecting to get hit 'in the chest ever since this fighter had begun its attack. When he hit me in the leg, the first thought that entered my mind was "What a crummy shot you are!"

Suddenly, the lead stopped pouring through our plane, and we learned after we landed that the rest of the formation had sent our attacker down in flames. I've had, some awful feelings in my life but never as bad as seeing someone shoot at me, and I couldn’t return fire. The remaining fighters continued to attack us for about 15 minutes. By this time we were about 5,000 feet above the water and traveling better then 400 miles an hour, (those planes were red-lined at 350 miles an hour). The rest of the formation was a group of tiny specks ‘way behind us. The fighter's were running low on gas and ammunition, so they had to break off the attack. It was certainly a wonderful feeling to see them head back to Sicily. We now had time to look over the situation and put on our parachutes.

The two damaged engines were still smoking a great deal, but there was no flame visible any longer. Every gas tank in the plane had been hit, and gas was running everywhere. One could see a solid sheet of liquid trailing beyond the tail of the plane from the wing tanks. Gas was flowing more than three inches deep beneath the catwalk at the waist gun positions from the damaged bomb bay auxiliary tank. This gas was flowing out of the plane through the tail turret. The control cables were damaged, and the part of the ship I could see looked like a sieve. Mac had already gone forward to the radio and was sending our position and an SOS. We didn’t think we would even be able to reach Malta with the gas supply we still had. Joe Rose, the engineer and top gunner, came back to see how we had made out in the fight. When I saw him, I expected him to die on the spot. The whole left side of his face was covered with blood. We learned from him later that flak fragments had riddled his turret dome and cut some of the electric cables controlling the operation of his turret. He had stooped over to try to repair the cables when a fighter put a cannon shell through the turret. Just at the point where his head had been a few seconds before. The explosion of the shell knocked him out of the turret, stunning him for a few moments. His head was cut in a number of places with cannon shell fragments.

When Joe came into the back of the plane, he helped me get Pat fixed up as best we could. He had three machine gun bullets in each foot. There wasn’t too much we could do for him since we didn1t have any morphine aboard, and he couldn’t smoke a cigarette with all that gas around. Therefore, Joe returned forward to help the pilot. By this time, we had slowed down enough so that the rest of the formation that was left closed in behind us to protect our tail. Mac called Malta to ask for some Spitfires to escort us in (if we could get that far), so I was anxiously watching for them to appear.

About five minutes after the ME 109’s had turned back, six fighters appeared above us and to the right (three o’clock, high). When I saw them, I thought, “Thank God the Spits have arrived”. Suddenly, however, they began to peel off, spitting flame and lead as they came. Then I knew we were in for another fight. Apparently the Germans figured they had a kill, so they sent another flight of ME 109’s from the southern tip of Sicily to cut us off. I never felt so extremely helpless in my life. When they attacked, I just knew that our last hour had come since gas was still flowing everywhere. The two engines were still smoking badly, but the rest of the planes closed in very close behind us. I felt like lying down on the floor and crying like a baby, but something -- self-preservation, I guess -- kept me from doing it. I never knew before that I could pray, cry, and swear at the same time, but I certainly did then. I swore a blue streak every time my bullets didn't go where I wanted them to. These boys were really blood-thirsty because they’d come so close through our wall of lead you, could almost see the expressions on the pilots I faces. The battle continued, and every minute we expected to be blown sky-high when one of those cannon shells exploded near the gas tanks. However, after what seemed years (but was actually only a little over an hour), we finally sighted Malta, and then the Spits chased the ME 109’s off as we crossed the coast. We were to learn, though, that our troubles still weren’t over. Most of our gas had drained from the tanks by now, but there still was too much to suit us. The runway on Malta was actually too short for heavy bombers to land safely, and there was a 50 foot drop into a stone quarry at the end to complicate matters a little. As our hydraulic system was shot out, we didn’t have any landing flaps. Therefore, we had to land between 140 and 150 miles an hour instead of the usual 120 miles an hour (it had to be flown in). With no hydraulics, it also meant no brakes. However if we landed on the belly of the ship, we were afraid the sparks from the runway would cause the plane to explode since there was still too much gas for comfort. After circling the field as long as we dared (the sun had already set), the pilot finally decided to land on the wheels and hope he could stop the plane before it reached the stone quarry. We hit the runway at 145 miles an hour. The flat tire immediately caused us to swerve, and the pilot fought to straighten the plane but. All he succeeded in doing was make the ship zig-zag down the runway .We were still going about 90 miles an hour when the right landing gear collapsed dropping us down on the belly of the plane. We slid along on the belly for about 100 yards, and the sparks (I swear they were as big as basketballs) seemed to fly a mile. By some miracle, however, we still didn’t explode. We stopped about 100 yards short of' the stone quarry. We had no sooner stopped sliding than an ambulance drew along side, and someone climbed through the waist window to help me get Pat on a stretcher. We must have gotten in on the gas fumes because no gas ran out on the runway when we stopped. Take it from me, we really patted good old Mother Earth when we climbed out of the badly damaged Pink Lady. We almost cried when we saw the condition of the old girl. However, we were hauled off to the hospital to be taken care of, so we didn1t get a very good look at her that night. Pat was the only one of us that had to stay in the hospital all night. The rest of us were allowed to go to some stone barracks after the medics had taken care of our wounds. The next morning we walked back to the Pink Lady, and I think that walk was the most wonderful one I have ever taken. Of course, we didn1t walk so very well, but at least we still were able to walk. When we looked over the old girl that morning, we patted the ground again. She was more badly damaged than we had realized the night before. A British officer was counting the holes in her when we arrived on the scene, and his total was about 700 (the belly was caved in so that no count could be made there), so you can see she was beaten up a little. Even the propellers had several holes apiece in them. The last we saw of the Pink Lady she was being readied to be pushed into the stone quarry.

About noon the same day, we began loading what was left of our equipment into one of the planes that had covered our tail the day before. We took off for our base at Abu Sueir with them about 1P.M. This ship had only two holes in it from the fight the day before, but our crew was still rather shaky when we took off. We had to leave Pat behind in the hospital (he eventually lost both feet). The rest of us were quite nervous all the way back to our base. It was a most glorious sight that night when we circled over the friendly lights of Abu Sueir to make our landing. The thing that hurt us most, though, was the fact that Joe Taulbee and the rest of the crew he was flying with that day had not been able to get back.

The website 376bg.org is NOT our site nor is it our endowment fund.

At the 2017 reunion, the board approved the donation of our archives to the Briscoe Center for American History, located on the University of Texas - Austin campus.

Also, the board approved a $5,000 donation to add to Ed Clendenin's $20,000 donation in the memory of his father. Together, these funds begin an endowment for the preservation of the 376 archives.

Donate directly to the 376 Endowment

To read about other endowment donation options, click here.

Reunion

NOTE change in the schedule !!

DATES: Sep 25-28, 2025

CITY:Rapid City, SD

HOTEL: Best Western Ramkota Conference Hotel; 2111 North LaCrosse St., Rapid City, SD 57702; 605-343-8500

Click here to read about the reunion details.