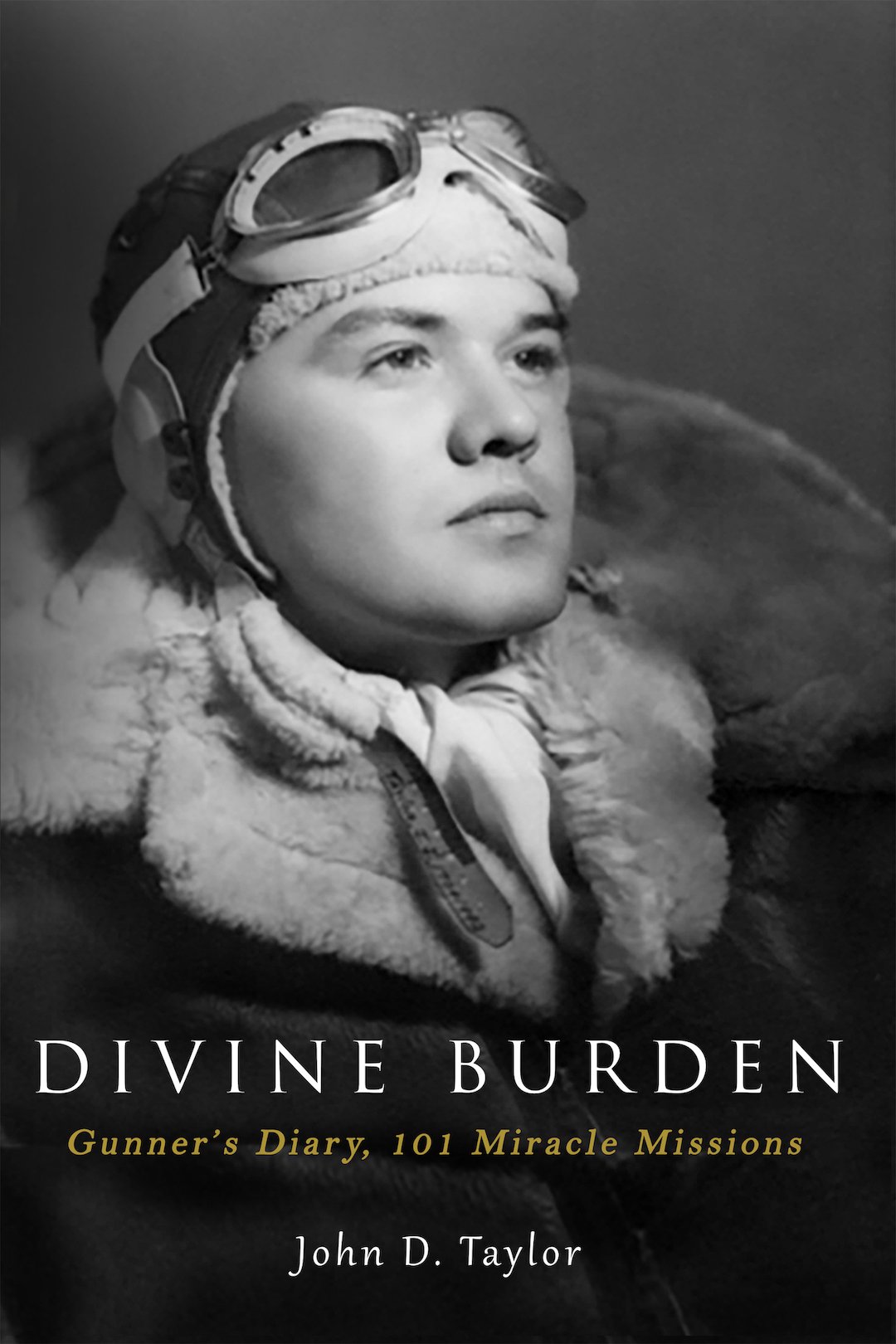

William C. Schmitt, Interview

Lt. William C. Schmitt was interviewed in 2004 by his daughter Nancy Schmitt Burns. It was transferred from tape to CD, transcribed and submitted to The 376th Heavy Bombardment Group’s historian, Ed Clendenin on September 25, 2016

I was attending Rutgers and enjoying my life there, playing football, and doing some studying. When we were playing poker one Sunday afternoon and listening to football on the radio, when suddenly they broke in to announce Pearl Harbor had been bombed by the Japanese. So we continued playing and then started talking about the war more than we had been up to that point.

After a day or two we decided things got worse in the war, we were losing more ships and losing battles. I decided I guess I was going to have to do my part and I would like to become an aviator. In those days you had to have two years of college to be accepted into the Naval Air Program. I decided that’s where I’d like to go, into the Navy, as part of their flying service. I applied at the Navy Center at 120 Broadway (New York City), and was accepted. Due to my medical history I had due to a broken nose that had been repaired, they told me I had to have a further operation. So I went down the street to 34 Whitehall Street and was told my nose was ok in the Army Air Corps. So I accepted their pre-induction, and told the Navy people to send me a discharge since I had already been sworn in to their training program.

From there on it was down to a number of bases until I found my way down to San Antonio, Texas, and started my pre-flight training. I guess it was October of ’42. I completed my training and went from there to Chickasha, Oklahoma, and flew PT-19s for my actual air training. In San Antonio it was all school work. Meteorology, Morse code and many other types of things.

Nancy: Was that difficult, to learn all that?

Well, it wasn’t difficult. It was easy compared to the college work. I went to Chickasha, to the primary school, which was my first flight training, and then I went on to basic training in the next larger size air craft. After that for a couple of months I went to Altus Oklahoma where I got my wings, finally, in August of ’43. I was in class 43H.

Nancy: Did you get much time off?

We got time off but you had very busy days. When you weren’t studying, you were waiting for time to fly, and when you weren’t doing that you were doing typical training courses. I was very busy. I had a few days off during each month, but not too many. As you know, the war wasn’t going too well, so they had to rush us through and get us into combat as soon as possible. So from there, after getting my advanced training, I finally ended up flying B-24s in Pueblo, Colorado in August of ’44. From there I went to Herrington, Kansas to be assigned to the actual destination overseas, which turned out to be Italy, in the 15th Air Force.

Nancy: You were telling me something the other day about how at one point one of the flyers was killed during a training mission and they wanted you to go back to Buffalo to see the family.

That happened in primary training. A young fellow from upstate New York, George Savella , we were bunking together. Everything was in alphabetical order then. One day he went out on his training mission in a PT-19 and didn’t come back. They found his plane out in the desert somewhere out in the plains of Texas or Oklahoma, lying flat on the ground and he was in it still, dead. It looked like the plane had come down almost vertically but I don’t know how that could happen. There wasn’t much damage that way but he was in the plane and he was dead. I was asked if I’d like to accompany the body to upstate New York and I declined as I didn’t see any purpose going up there and it would have meant delaying my training work. I was very gung ho at the time, being twenty one years old that’s what happens. So, at any rate, I finished my training and went over to Italy, stopping at points over there; Dakar, North Africa. We flew from Fort Lee, New Jersey, to South America, to Dakar to various African bases, to Marrakesh and to Tunisia, Algiers and then we flew on over to southern Italy. At Manduria, a little town in the heel of the boot, where I started my missions.

Nancy: What was the name of your squadron, the number and all that?

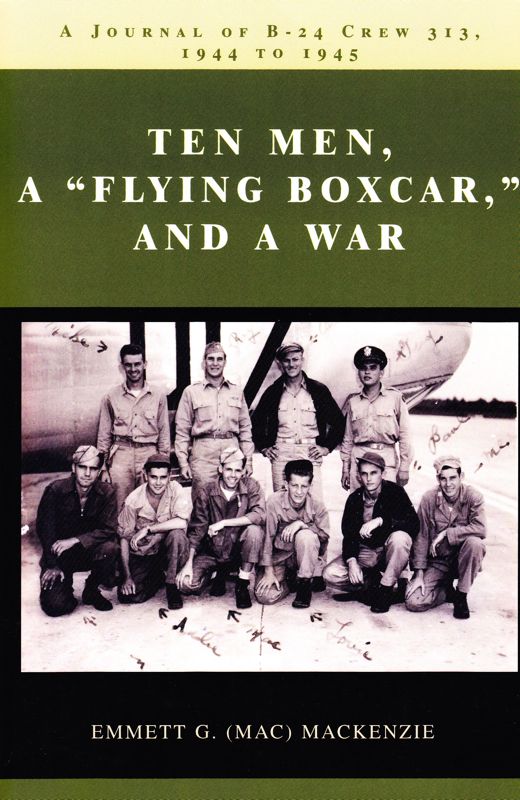

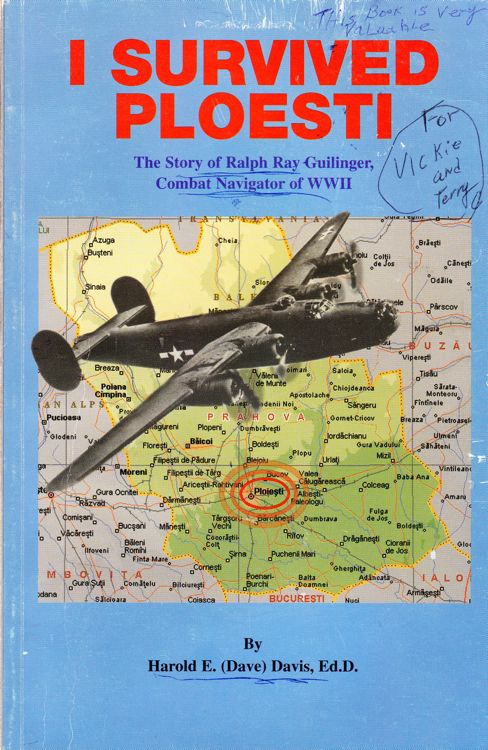

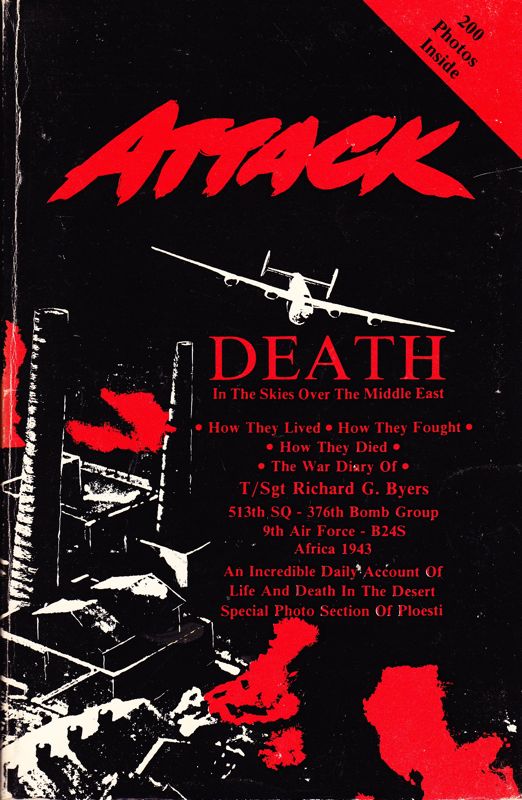

I was in the 376th bombing group, part of the 15th Air Force, and the squadron in that group was the 513th bomb squadron. I was in the graduating class of 43H, and this was 1944 when I finally arrived at the destination in southern Italy. From there we flew missions over southern France, which was under the German’s control and other Mediterranean , Adriatic countries, Yugoslavia, Romania, Hungary, Germany, all those countries. We had a total of sixty- two missions over targets. That has to be explained a little bit. Over so many hours, I’m not sure if it was ten or eleven hours, in the air, you would get credit for two missions on those extremely long flights, as you probably read by now, in books about the war. It was terribly cold up there, sometimes fifty below zero, and after that length of time in the air you were ready to get back to your home base….which didn’t happen for everyone. There were many, many casualties. There weren’t as many as the beginning of the war, but there were a lot more in 1945. We lost some planes but there was complete superiority in the air, both fighters and bombers.

Nancy: So Dad, how many missions were required before you could go home?

Originally, at the beginning of the war, it was twenty-five missions. I’m quite sure that those bomber pilots had a much more difficult time completing twenty-five than we did fifty missions. Remember that I had fifty- two missions but whenever it went over ten hours we got credit for two missions. We still had to fly at least approximately thirty- five missions to get up to that fifty missions.

Nancy: When you were flying the missions, what were the conditions in the plane?

Terribly cold. We were notified the night before whether you were flying the next day ‘s mission or not. Generally if you fly one day you’re not required to fly on the second day in a row. They notify you on the night before who’s going, we go to bed, those who are not going the next day would find other diversions such as another poker game. There was not much drinking at all because we didn’t have anything to drink. The Italians had something they called rooster blood, which was a very rough and tough red wine. But most of us couldn’t stomach that. None of us were drinking at that age, a beer now and then.

Nancy: When you weren’t flying, did you stay on the base?

No, we’d go into a little town, Manduria. The air base was maybe five miles from there.

Nancy: There was really no food around?

Well, the Army food. If you wanted an egg for breakfast, you had to pay extra for it. They would get them from local farmers in the area. I don’t know if these eggs would pass our inspection now a days, but we thought they were wonderful then.

Nancy: But they didn’t have ristorantes with pasta around?

No, not in Manduria. In fact, you took your life in your hands if you ate some of the local food. The same as if you went to Mexico in the present day.

Nancy: Was food scarce?

Yes, food was scarce. We gathered cheese and eggs and so forth, together to give to this little Italian boy that kept our barracks clean.

Nancy: What was his name?

Vittorio Emanuel Monsa was his name, from northern Italy. His family had fled into southern Italy when the Germans were driven out of southern Italy. In fact, the air base had been occupied by Germans up to two to three months before we got there and most of the signs around the old, dilapidated barracks that we were in were written in German. It had one big master shower room. At least we could take showers, which was more than the poor guys in the front lines could do.

Nancy: So what did Vittorio do with your cheese and eggs?

He took it home to his mother. She was going to make a pizza for us. Which, when he brought it back, was nothing like the pizzas we knew. We thought they kept the eggs and the cheese and just gave us a plate full of dough! But that was to be expected. We really ate pretty well. I was very happy I was in the Air Corps.

Nancy: What kind of rations did the military supply for your missions?

Well, when we’re on a flight, the only rations we had were...we’d take a big gallon can of mixed fruit and that was the meal we would have during the day. So it would be breakfast at the base before we took off, and we’d fly anywhere from two to four in the afternoon.

Nancy: Was it a big can of fruit cocktail?

A big can of fruit cocktail and ten spoons. (laughing at the memory) If we were lucky we had ten spoons. Everybody ate at the same trough!

Nancy: Wouldn’t it freeze?

It would freeze, yes. You’d have to wait until you came down to lower altitude, sometimes so you could thaw it out and eat it. It would be frozen solid.

Nancy: Did you have special clothes or anything?

Yes, we had heavy flying suits. That was enough to keep you warm til you got up in the air. If you put your heavy suit on and then the electric suit on and did nothing but sweat up there in fifty below zero weather you would just get frozen all over, practically. You were very, very cold and you were very happy, always, to get down to a lower altitude.

Nancy: Did you get frostbitten fingers?

Frostbitten fingers and around the mask that we wore for oxygen. Up at that altitude you had to depend on your oxygen to keep you awake and to make reasonably sensible decisions.

Nancy: Did you always fly in a formation?

You took off and if you were lucky, loaded with bombs, you got off. I remember taking off when the plane in front of me crashed and we had to fly through the smoke. Their plane exploded before it got off the ground. It was so heavily laden with bombs that it couldn’t get enough air speed to get going. Then if you were fortunate enough to take off, everybody would circle around the air base for about ten to twenty minutes while the rest of the planes were taking off and then you could get in a formation. You had to be in a formation once you were over enemy territory to protect yourselves, because every plane depended on the bombers around them. Each bomber had a number of guns, tail gunners, turret gunners, nose gunners, waist gunners, all to fight off German fighters. There was no other way you could fight off the fighters and the flak. Flak is when they shoot off a lot of air exploding bombs they shoot up at you and they set the timing on it so it explodes at your altitude. They determine your altitude by radar, even though it was in the early stages then. They would determine your altitude and to thwart that we would carry boxes of shredded tin foil and through it out the windows to make the reading they got on their radar erroneous so they couldn’t tell the exact altitude, but they seemed to do it anyway. You’d be flying through it and the enemy fighters would leave you when you went over the target because they didn’t want to be submitted to the flak attack. Once you got out of the flak the fighters would come at you again. Then you circle around and you’re heading back to meet your own fighters. Later in the war, when the P-51’s came out which could fly further, the fighters would meet you closer to the target. From the bomb drop and meeting your fighters you were at the mercy of the Germans. We were very happy when we’d see some of them show up because then most of the time the Germans would disperse. But there were many dog fights between our fighters and the German fighter planes.

Nancy: Was your plane ever hit?

No direct hits, that’s why I’m here. We had holes in a wing and in the fuselage.

Nancy: What does is feel like when the flak hits the plane?

When it hits you, you don’t feel it. You see all these black puffs bursting around you and you know that’s where the flak is, but you couldn’t avoid it. If it was fired up and it happened to hit you, that was the end of your plane. But if it exploded a couple of hundred feet this way or that, you were past it. Unless it was in front of you, then you had to fly through it and all the pieces of metal are in the air, floating. The bomber planes couldn’t break the formation, because if you’re depending on the five guns or six on each plane, depending on how many were flying, you had twenty planes in a row, they were all firing at a certain fighter. You depended on each other, you never really knew who got what, generally, if they got anything.

Nancy: Did you ever lose an engine?

If you lost an engine on the way out you would come back. You could lose one engine without any difficulty. If you’re going out there and you lost an engine later on you’d have trouble keeping up with the rest of the bombers and the whole formation would be slowed down for you. Then you’re trying to get away from the target and if you become a straggler the Germans would be after you by yourself out there.

Nancy: Were you given instructions on things not to bomb, any sort of historic buildings?

It all depended on where you were going, Certain countries had religious buildings, hospitals etc. you tried to avoid, but pinpoint bombing was not then what it is now. We had what you called a Norden bomb site during the war for high level bombing. You couldn’t be positive, however you were sure enough in most cases.

They gave us gave us fifty dollars in case you want to buy your way out of prison. At that time in Yugoslavia there were two factions, Tito and Mikhailovich. Each had control of opposite factions in Yugoslavia . If you landed you were always instructed to find out if they were Tito’s people or Mikhailovich’s. You didn’t want to show any preference to one or the other. The fifty dollars could buy you safety. You had to turn the money in after every mission.

Nancy: Dad, when you were flying these missions, did you ever see people bailing out of planes?

Oh, yes. I saw planes going down, people bailing out. Some of these pictures we see now on TV and so forth, are pretty true.

Dad met and married Lt. Marianne Kehoe, an Army nurse from Illinois. He had four daughters, worked for Ingersoll Rand in Manhattan, and lived in Bergenfield, New Jersey, his home town. When he retired he moved to his home on Lake Owassa, New jersey. He passed away on April 25, 2010 and his family included the presence of a United States Air Force honor guard at his memorial.

The website 376bg.org is NOT our site nor is it our endowment fund.

At the 2017 reunion, the board approved the donation of our archives to the Briscoe Center for American History, located on the University of Texas - Austin campus.

Also, the board approved a $5,000 donation to add to Ed Clendenin's $20,000 donation in the memory of his father. Together, these funds begin an endowment for the preservation of the 376 archives.

Donate directly to the 376 Endowment

To read about other endowment donation options, click here.

Reunion

NOTE change in the schedule !!

DATES: Sep 25-28, 2025

CITY:Rapid City, SD

HOTEL: Best Western Ramkota Conference Hotel; 2111 North LaCrosse St., Rapid City, SD 57702; 605-343-8500

Click here to read about the reunion details.