William Smither Story 2

S/Sgt. WILLIAM R. SMITHER

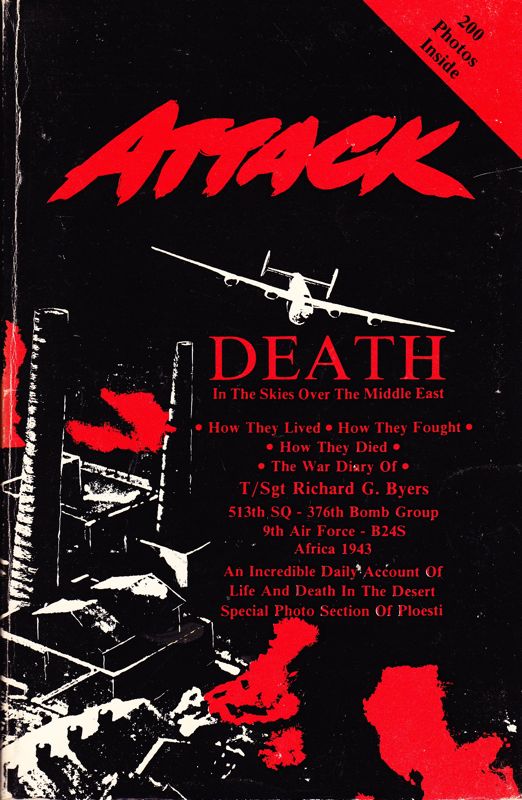

15th Air Force, 376th BG, 512th BS

I graduated from Lafayette High School and was single. I was interested in becoming a pilot and talked to the recruiting officer who had been putting me off, and I received a notice that I was being drafted. It was in the fall of 1943. I told them I would like to be in the Air force and become an aviation cadet. They told me to get in line with the others, but they did put me in the Air Force.

I was sent to Keesler Field, Mississippi, for basic training. I asked to be put in the aviation cadet program, but was told they didn’t need pilots. We finished basic training, and I was to leave on Thursday. Bob Hope was scheduled to appear at Keesler Air Force Base on Sunday. I asked the Sergeant if I could get sick or something so I could stay around and see him. The Sergeant said “Get out of here.” Bob Hope went all over the world performing for the troops. Young people today don’t even know who he was.

I was given a choice, and I went to Air Force Gunnery School at Tyndall Air Force Base at Panama City, Florida. There was a race track that was almost in the shape of an oval. They had a flat-bed truck with a ring in the center of it. We would get in the ring, and the truck would be driven around the track. People in the woods around the edge of the track would shoot clay pigeons. We would try to shoot the clay pigeons with our shotguns. We also had movies and visuals. We were trained to fire all the guns on the plane.

They put the plane crews together here in the United States and sent them over as a unit. We were a crew for a B-24 bomber, and it was made up of ten men. The B-24 was built in the Ford Willow Run Plant at Detroit, Michigan. It was also manufactured in the Consolidated, Douglas and North American plants. The early versions of the B-24 did not have a machine gun in the nose, but this was corrected in later models. The ball turret (the turret on the bottom of the plane) could be cranked up into the fuselage. The B-17 did not have this feature.

Planes towed targets, and we shot at them during practice. Each machine gun shot different colored bullets. When they retrieved the target, they could count the different colored holes and determine the number of hits for each gunner. When we were on the ground we fired 50 caliber machine guns with regular ammunition. The trajectory of the graphite bullets was different from the regular bullets, and this tended to throw us off. I was the tail gunner and had a turret which was hydraulically operated. It had a sight which was an orange colored ring with a dot in the center. There were two 50 caliber machine guns, and each had its own ammunition belt.

We were assigned to the 15th Air Force, 512 Bomb Squadron, and 376th Bomb Group. They had plenty of planes at that time, so we went over on a ship. It was the U.S.S. America. It had been a luxury liner before the war and had been converted to a troop ship. It was old, and it took us fourteen days to get to Italy. We had to zigzag all the way to avoid submarines.

Red Skelton was on the ship. He was assigned to the Transportation Corps. And he ran all over the ship entertaining the troops. He was a character. He had a book and said he had the names of all the officers who had given him a hard time in it. He was going to fix them after the war.

We docked at Naples, Italy, and I looked over at the rail and saw Marvin Nicholson. I had gone to school with Marvin at Lafayette. Our crew was sent to San Pancrazio, Italy, and his crew was sent to Venosa, Italy. Marvin was the ball turret gunner with the 485th BG, 830th BS. On April 11, 1945, he was on a raid, and they were hit by flak. Shrapnel hit the copilot above the ankle and severed his leg between the ankle and the knee. They put tourniquets on it to stop the bleeding and put him on the floor behind the pilot. The pilot was hit in the neck and was partially paralyzed.

They called Marvin up to sit in the copilot’s seat because he had some previous flying experience. The pilot gave him directions. They asked the crew if they wanted to bail out over Italy or stay with the plane. They decided to stay with the plane. The number three engine was out and the number four engine was not running properly. The number three engine on a B-24 provides the power for hydraulics, so they had no brakes or flaps.

Marvin helped the pilot get the ship back to a field in Jesi, a town in northern Italy, and assisted him in landing it. The nose gear came down, but the back wheels would not come down. The pilot raised the nose and brought it back down breaking off the nose wheel. They slid the big bomber in without wheels. They took the pilot and copilot to the hospital, and Marvin received the Distinguished Flying Cross. Few gunners in the United States Air Force ever received this award.

The B-24 bombed from an altitude of around 30,000 feet, and the plane was not pressurized. We wore big bulky flying suits that had little wires going down the legs and the arms. We plugged the suits into electricity, and they were supposed to keep us warm. Sometimes the wires would break, and there would be no heat in that part of the suit. The suits came in small, medium and large, and you didn’t get the same suit each mission, so you didn’t know if the suit worked. We wore goggles over our eyes and an oxygen mask over the lower part of our face. The temperature could get to thirty or forty degrees below zero.

When you went on a mission, you didn’t get the same plane each time. The plane you used on the last mission might still be undergoing repairs. You took the plane assigned to you, and some of the planes were much better than others. I remember on one mission we had a relatively new plane, and our pilot commented about how good it was.

When the raids on Germany first began, a complete tour of duty was twenty-five missions. The odds were against a crew finishing the twenty-five missions. Later in the war, we had more control of the sky, and German fighters weren’t as much of a problem, so they increased the number of missions to fifty.

A squadron put up seven planes. There was a lead plane with a Norden Bomb Sight, and the bombardier in the lead plane would drop his bombs, and the following planes would toggle on his bombs. If the lead plane dropped bombs on the near edge of a large factory, the bombs from the following planes would spread up through the rest of the factory. This was because of the slight delay between the time the lead plane dropped its bombs and the time the following planes toggled their bombs. When the bombs were dropped, the plane would become much lighter and would bounce up in the air. The planes were in formation, and suddenly there would be bombers bouncing around all over the sky. I thought pattern bombing was messy.

When we first got to Italy, they sent us on milk runs. They would select a bridge or some other target where the flak and fighters were no problem and send us to bomb it. This was to give us some experience before they sent us to bomb factories and other heavily defended targets.

The Germans had two fighters they used against our bombers, and both were effective. The ME-109 was the better known of the two. The other was the FW-190, and it was slightly faster than the ME-109. They also had a twin engine ME-110, but they were few in number. The Germans were having trouble getting enough fuel because we had been bombing their refineries. This caused the fighters to be less of a problem toward the end of the war, but the flak never did let up.

When we went on a raid, we would be accompanied by the P-51's of the Tuskegee Airmen. It was comforting to see the red tails of their fighters. They had an outstanding record.

Our pilot, Richard S. Ritter was from Allentown, Pennsylvania. Our co-pilot, Ralph G. Wilson was from Camas, Washington. Our navigator, Donald J. Anthony was from Buffalo, New York. He was Italian and could speak a little Slavic which was to come in handy later on. Our ball turret gunner was Michael Pagnotti from Brooklyn, New York. Our Engineer, Albert A. Hortert was from Renfrew, Pennsylvania. Our radio operator, John M. Mischel was from Detroit, Michigan. Our waist gunner, Max Norman was also from Buffalo, New York. Our top turret gunner, Leonard A. Phillips, was from Camden, New Jersey.

I completed twenty-two missions. We were sent to bomb a German Air Base that was used for ME-262 fighters. This was a jet plane the Germans developed, and it became operational near the end of the war. It was extremely fast. Our turrets were operated by motors, and the jet planes went by so fast the turrets could not keep up with them. It was a sunny day, and we bombed from 30,000 feet. As we neared their field, I could see them taking off and heading in all directions because they knew we were coming. I expected them to come up where we were and try to shoot us down, but they did not. They were probably short on fuel.

[Editor's note: William then described the events of January 15, 1945. We have put those on a separate web page. Click here to read those comments. ]

I used the GI Bill to attend the University of Kentucky after I came home. I received a degree in Metallurgical Engineering and worked for several different foundries.

I was in sales and marketing with a foundry in Pennsylvania and was traveling with a sales representative of the company. We visited a small machine shop and were in the reception area. I saw pictures of B-24's on all the walls. I told the receptionist of my background with the B-24 and asked about the pictures. She said the shop owner had been one of the managers of the Willow Run Plant. She told him I was there and explained my story. He came out, took me to a conference room, and told me about some of the history of the plant. We had a good discussion.

Author: William W. Woodward, Lexington, KY

This first appeared in the book: A MILITARY HISTORY OF THE MEMBERS OF GARDENSIDE CHRISTIAN CHURCH, 2009.

Epilogue

Mr. Woodward graciously gave his permission for website publication in July 2015.

The website 376bg.org is NOT our site nor is it our endowment fund.

At the 2017 reunion, the board approved the donation of our archives to the Briscoe Center for American History, located on the University of Texas - Austin campus.

Also, the board approved a $5,000 donation to add to Ed Clendenin's $20,000 donation in the memory of his father. Together, these funds begin an endowment for the preservation of the 376 archives.

Donate directly to the 376 Endowment

To read about other endowment donation options, click here.

Reunion

NOTE change in the schedule !!

DATES: Sep 25-28, 2025

CITY:Rapid City, SD

HOTEL: Best Western Ramkota Conference Hotel; 2111 North LaCrosse St., Rapid City, SD 57702; 605-343-8500

Click here to read about the reunion details.