Otto A. Tennant

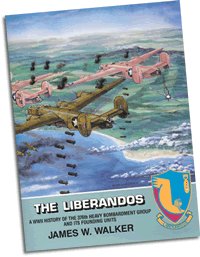

Otto A. Tennant was a navigator on the Morris Mansell crew. They were assigned to the 515 squadron.

He wrote the following about his time in the service and with the 376:

The B-24 experience during World War II of Otto A. Tennant

There are three statements that should be made for a discussion of this subject.

1. The topic was recommend by your vice president walkup

2. The leaders of bombers were pilots and all others were advised they were the leaders and all others followed.

3. The myths of the twenties and thirties become the facts during a persons sixties and seventies.

The subtitle of this talk should be how a devout coward survived World War II.

When Pearl Harbor was attacked I was a student engineer on what was called a supervisor for student test engineers at General Electric doing final electrical and mechanical testing of submarine dc motors and generators. A buddy and I were leaving to go to a movie Sunday night when we heard the news. I remember stating that now thousands would volunteer, but as a nation we were ready to even defend ourselves. My buddy state, don't worry Otto you have a high draft number and within a month you will have a two year defense deferment. He was correct.

In July 1942 my father called and suggested I dodge the draft since he knew all single men under the age of thirty would have their deferments canceled and be drafted into the army.

I got two days leave to go to Washington to dodge the draft.

My cousin was in Washington D.C. with the FBI and he knew the various departments and recruiting offices. So I went to the navy department and when they found I was 6 foot 2 inches tall and weighed 139 pounds they suggested I go the army. I then went to the engineer corps and they said they would enlist me in their officer training corps and if I survived six weeks I would be a second Lt. And overseas in about 3 months.

This caused me to look for another possibility - the army air corps and that time was looking desperately for weather officers. Since I had a degree in engineering with two years and one quarter of math they advised they had an opening at MIT in the November 42 class of meteorology. I accepted and was sworn in at Fort Devens, Mass. With a physical waiver - eyes and weight.

Graduating in September 1943 as a 2nd Lt. I was sent to Harvard, Nebr. As asst. base weather officer. I liked the work, but I hated being officer of the day on the base every 10 days. In October 26 of the meteorology officers from the MIT class were contacted to see if the wanted by student officer candidates for navigation. The army air corps needed weather officers to fly combat and bring back both navigation information and weather. I saw flying officers did not have to be officers of the day so I volunteered. Once again with a waiver on my sight.

Graduating in March 1944, I was assigned to the overseas training command for B-24s located in Boise, Idaho. Since Marjorie and I wanted to get married before I went overseas, I contacted Col. Kane for delay in route to get married. It was granted.

When I arrived, I found the crew I had been assigned to had a new navigator, and since I had a waiver for glasses they assigned me to permanent staff as instructor to the crews for refresher on navigation and weather. This was spectacular duty, and at Boise my wife and I felt we were on an extended honeymoon.

In august, Captain Mansell arrived to obtain a crew. He had been a navigator and flew 25 missions from England and north Africa in B-17s and came back to the states to take pilot training and wanted to go overseas to fly a tour as a navigator.

He was unhappy with his navigator, and one day I was requested to take a flight with his crew on a training flight to San Francisco and back on two different routes. There was no problem and I thought nothing of it. A week later, I got orders going with Mansell's crew overseas - we knew not where. I also found I was given a waiver, with a prescription for two more glasses. I was to wear a second set of glasses during each flight. The devout coward had been clever up to date, but it didn't look promising.

My wife had full confidence in me, and said she knew I would come through o.k. and she would pray for me each night. She did and I did come through.

We had trained in B-24s and found that our orders were to go to Topeka, KS and pick up a plane to fly overseas. We also knew we might go to Alaska or Italy. The pilot and I didn't like the idea of flying over the northern Pacific Ocean to the outer Aleutians to bomb the Japs on the remote island. If we had to ditch in the ocean we were advised we would have to be picked up within 30 minutes at most or die of hypothermia. Italy looked better. We got the approval.

Our route overseas were to Bangor, ME; Gander Lake, Newfoundland; the Azores and Marrakech, Morocco. At Marrakech our pilot found he had a friend at Algiers, so we stopped there for two days en route to our delivery point at Georgia, Italy. The plane was taken from us and we were sent by truck to San Pancrazio to be with the 515th bomb squadron, 376th bomb group. The devout coward felt happy again, because they had the best record of bringing the men back safely.

Our missions started October 4, 1944 and the crew ended their tour march 23, 1945. Since I go to rest in Bari, Italy from January 19th to March 8th I didn't finish my tour until April 5, 1945. The last mission for each person in our bomb group was known as resurrection day, each one who finished a mission got a bottle of bourbon or scotch from the flight surgeon to do with as he pleased. I went to the officers club and for the first time in my life - and my last - with the help of "fellow friend officers" I soon got rid of that and so the bartender and all the others get saluting me the rest of the night with wine. On April 6th I woke up with the damnedest headache, the entire world turning and I feeling I would loose all my insides at any minute. Since I was a novice I took a huge drink of water and wow! It was awful. Lt. Duncan had pity on me and took me to a B-24 still at the base and I breathed pure oxygen for about a half hour and felt lousy the rest of the day.

April 7th Col. Wimberly gave me orders, which I personally took with a jeep to 15th hdqtrs in Bari, to get final orders to go home.

There were no heroes in our 376th BG. Col. Graff who was a civilian in uniform, stated the we civilians should get the job done and go home as soon as possible. Later Col. Fellows took over. He was a West Point graduate and part of the WPPA. Things changed when he came on board. We saluted. We wore dress uniforms off the base and I will not say any more since the WPPA probably can still "strike" today.

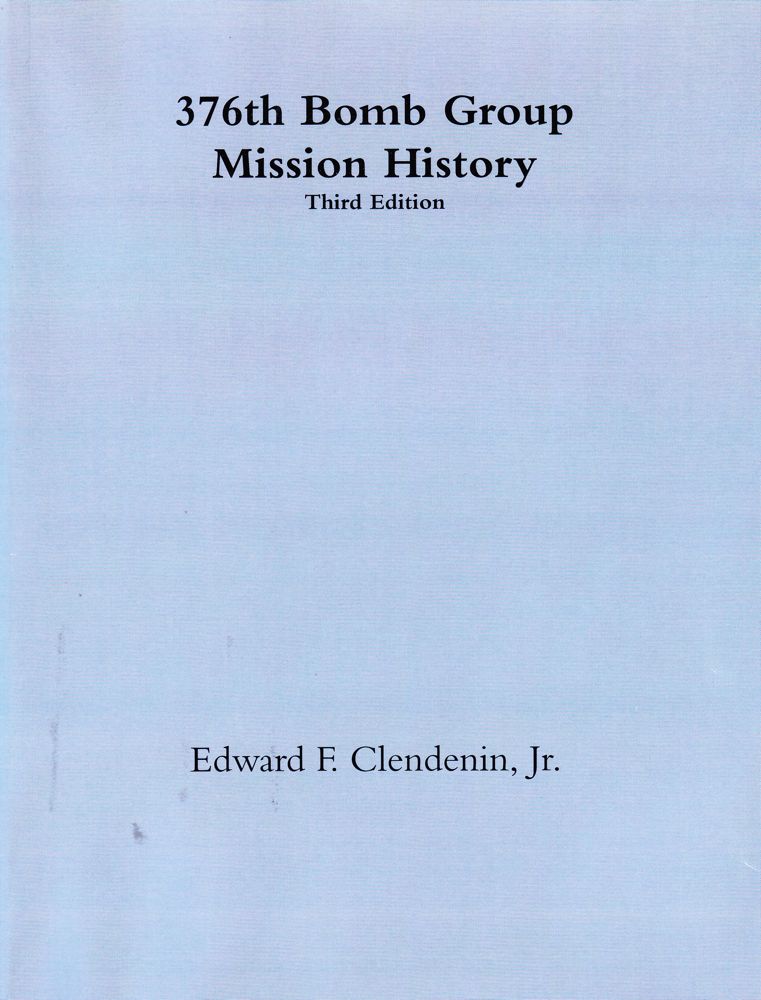

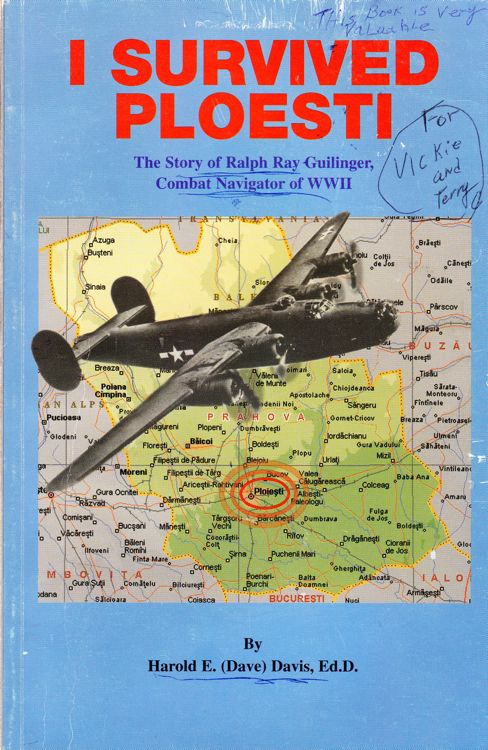

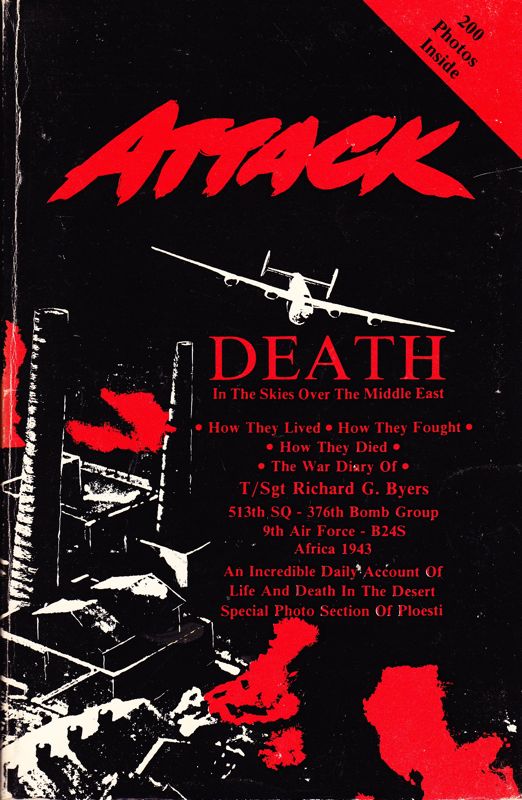

I flew 50 combat missions in the B-24. Only heroes found some missions to be a piece of cake. Most of us were apprehensive and superstitious concerning each mission. As you can see from this excellent history book, our crew was a replacement crew of many replacement crews. During 1944 until the Russians took over Ploesti oil refinery, Ploesti was known as the graveyard of the 15th air force. According to the records of the 376th every mission lost as least 5% of their planes and crews and many were in the 80 and 90%. In October of 1944 this devout coward was very happy the Russians had advanced and taken Ploesti.

In the history book showing the record of the 451 missions the 376th flew during World War II, I’ve noted what flights I flew and there were many that were a failure, some a partial success and some on target. Interesting to note that going to a target, I and most of the crew had to have oxygen at 8 to 10,000 feet. Coming back when we were over the Adriatic and had fighter cover, we could take off the oxygen a 16,000 feet and eat our lunch with no problem what so ever.

The first mission was a nerve wracking one. I was scared and could hardly make it to the plane. The mission was exciting, because our pilot being a former navigator was watching the bomb strike instead of flying formation - and our waist gunners screamed that we were going to crash into another B-24. It was caught in time - and our pilot from then on, said - Otto, your the navigator, not me. On this mission was where I saw why the B-24 was known in Italy as the flying coffin - the nose gunner saw a ball of fire where there was a B-24 and the waist gunner saw two blossoms. We prayed these fellows were save. Our tail gunner saw a B-24 go into a flat spin and go into the mountains. No man got out.

Another mission was notable that our squadron finally knocked out the Ferrar RR river bridge that had been a pain since most of the supplies from Germany came over this bridge. Our bombardier got another star for his air medal. The nose of our plane was damaged badly and all my maps and flight information was completely gone. The Col. asked me did I want to turn the navigation over to the deputy lead, and I advised him I had memorized the maps so well I’d see to it that we would not hit any flack. All our planes were in such bad shape, we could not take any more damage. I routed our squadron throughout the Po Valley and finally to the Adriatic, and then gave headings to Foggia, since I could get a radio signal from there. Three planes pealed off there for their wounded and we came back to San Pan. The Col. seemed to be impressed. Major Mansell and I weren't since we both knew that as a devout coward we had to memorize the flack charts before each mission.

You can see that we had many interesting missions, and I wrote the editor concerning five missions and sent a picture of our crew. Only one made it into the history book and our crew's picture was one of hundreds that had to be deleted. He did keep the report of the mission where we had to use and emergency landing field on the island of Vis.

The island of Vis was the only major island that the Nazis were never able to conquer. Tito and his partisans had their headquarters their. Allied construction crews built an emergency landing field and the British operated the field. It was a savior to many crews.

The editor asked all who submitted stories to have at least two others review the story to see if the memories of 40 years ago were accurate. In addition, he had all squadron commanders review the stories for accuracy. Where the commander was no longer available, he contacted the deputies. In our squadron these were Captain Barnes, Lt. Duncan and Major Mansell. I'd flown with all of them, so I was comfortable for them to review the stories.

On the 11th the weather was surprising good all the way to southern Germany. Most of our bombs overshot the target, the Moosbierbaum refinery, Vienna. Vienna's heavy flak caused major damage to six aircraft. Damage to one so severe it was destroyed in a crash landing at San Pan. Another was forced to make an emergency landing on the island of Vis. Captain Otto A. Tennant, 515th squadron navigator, on Captain Mansell’s crew described their experience.

"the flak over the target was the most intense this crew had ever seen. The plane has hit in many places but the most critical was the area of the inside gas tanks. In addition, the gas lines here also hit and in a short time much of the gas was gone from these tanks. However, due to the great skill of engineer McGinley the tanks were sealed off safely. Due to strong gas fumes in the plane captain Mansell ordered no change in the settings of the electrical controls, no ration communication and no further intercom for fear of an explosion.

At this time the Russian’s had advanced to an area in Hungary which would make the closest alternate airfield. The entire crew did not feel this was the proper alternate, since the Russian’s had been known to shoot down B-24s since the Germans had captured some B-24s and had used them to bomb the Russians. By this time we had lost altitude and were cruising at 14,000 feet. As navigator, I recommended that we try to land at the island of Vis off the coast of Yugoslavia which was in the control of Tito's partisans.

The fuel tanks on the plane indicated empty fifty to sixty miles short of the island of Vis. It was agreed to drop slowly down to conserve on the fumes and the navigator use pilotage with the assistance of the co-pilot to reach the island of Vis.

At the time of the hit to the plane until we landed I was so scared that I hoped a prayer would help, but the only thing that would come to mind was the 23rd psalm which repeated to myself over and over. Also, since we were not supposed to change controls the electric suit being set for 22,000 feet at -20 degrees centigrade it got hotter and hotter and by the time we landed at Vis I didn't see how it could get any warmer even if I was in Hades.

Due to expert piloting and wending our way through the mountain passes we landed on the strip on the island of Vis. The strip was so short, and I’m not sure but I believe grass, we skidded off the end of the runway but stayed upright and no damage. At the end of the runway was a British sergeant and when I climbed out with tears running down my face he calmly states, 'bit of a bloody go, captain?' All I could reply was 'right'.

That night Tito’s men fed us and gave us a place to stay. Most of the person in uniform were of boy scout age. They were very happy to see us and gave each member of the crew a red star to place on our caps that had been evidently cut out of tin cans and painted with red paint. These young boys had picked up a smattering of English and wanted to impress on us that the war would be won and the world would be saved by Tito, Stalin, Lenin and Mary. The rest of the crew continued talking the evening away with liberal applications of grapefruit juice and Yugoslavia gin. Some of us were so tired that he went right to sleep on the most comfortable floor I’ve ever slept on.

The landing strip on the island of Vis is on the bottom of a valley surrounded by hills similar to a saucer. We had been advised a C-47 would be coming to pick us up, since the majority of the time only fighters and C-47s could take off from the field. Captain Mansell and engineer McGinley checked the plane and found it could be easily repaired for emergency flight to our base and this was completed. Captain Mansell then elected to take off and not wait for the C-47.

At 10:00 a.m. Captain Mansell was at one of the runway with no wind, but ceiling and visibility unlimited. He revved the engines to full throttle before releasing the brakes and the plane started to roll down the runway. After the plane started to roll, as navigator I started trough the tunnel so I could be in the nose section as we came out over the Adriatic. I knew that Captain Mansell was always ready to take calculated risks but as I looked out of the nose and saw nothing but tree tops, tree tops and more tree tops up and up the mountain all I could think of - this is crazy - never thought that we might crash into the mountain. In a few minutes we came into the clear over the calm Adriatic and it was the most peaceful scene I’d ever seen or have seen. It was just a few uneventful minutes we were back in San Pan and going through briefing.

I really feel to this day there are easier ways to obtain a red star from Tito’s partisans".

The emergency landing strip on the small island of Vis, 33 miles off the Dalmatian cost of Yugoslavia saved the lives of thousand of crewmen and many hundreds of allied aircraft. It was held by Marshal Tito’s partisans as an amphibious operating base throughout the war - one of the few consequential Yugoslavian islands that were never occupied by the Germans. Tito had headquarters command cave on the island from which for a long period, he directed his Yugoslavia activities.

U.s. engineers constructed primitive 3500 by 100 foot gravel and pierced steel plank strip in a valley between the hills. British commandos operated the strip. A mixed bag of AAF technicians and civilian "tech reps" repaired many of the aircraft landing there. In most cases the aircraft were so badly damaged they were bulldozed off the strip and torn down for their spare parts.

Then there were occasions, such as the day thirty-seven B-24s crash landed on the Vis air strip, when they had to be bulldozed from the runway, regardless of their condition to accommodate the next emergency landing. On other occasions the strip was so busy, or crowded with crashes, that incoming aircraft had to bail their crews out over the island and send their crewless planes to their destruction, hopefully, at sea. Emergency medical services was provided and crewmen evacuated to Italy in a motley array of Canadian pt boas or flown out in the ever useful C-47. Many aircraft, as was the case with Captain Mansell's were able to clear the strip after refueling or after repairs. There were some that tied but didn't "make it".

Among the many crews saved by the Vis landing strip was former Texas Senator (and secretary of the treasury) Lloyd Bentsen’s. Secretary Bentsen, then a major and squadron commander in the 449th bomb group of the 47th wing, brought his 8-24 in a successful but rough landing with two engines out.

The devout coward checked out from the 376th to go the 7th replacement depot which was situated 24 miles east of Naples at a warm springs resort. Our intelligence officer, Captain Preble, took all the bomb stride photos I had of each mission and my navigator's log and secured them.

When I arrived at Miami, the customs officer said I could not bring those in the states. I indicated they had security clearance, but he stated they were to confiscated by customs. I wonder to this day if that was true, or was he getting information for himself.

I arrived home for two weeks r&r and then two weeks at Miami Beach. While at home on May 8th the war ended in Europe. When my wife and I got to Miami Beach many of the officers of the 376th stated I had enough points that I could be discharged. We found this to be true. At discharge time a colonel thought he was doing me a favor. He stated the army air corps would soon be their own air force and they would need graduate engineers in the service. He offered a five-year permanent commission as a captain.

I as a devout coward stated no thanks; I’ll take my chances in the civilian world.

We were sent to Jefferson barracks, and I had to stay two days to be processed. My wife took the train to Des Moines ahead of me. The first half day was processing, so four of us went to downtown St. Louis and purchased civilian suit with white shirt and ties. One of our group had a car and drove us all to Iowa. As we left Jefferson Barracks the guard saluted smartly and said,

"you lucky sons of b_____

The website 376bg.org is NOT our site nor is it our endowment fund.

At the 2017 reunion, the board approved the donation of our archives to the Briscoe Center for American History, located on the University of Texas - Austin campus.

Also, the board approved a $5,000 donation to add to Ed Clendenin's $20,000 donation in the memory of his father. Together, these funds begin an endowment for the preservation of the 376 archives.

Donate directly to the 376 Endowment

To read about other endowment donation options, click here.

Reunion

NOTE change in the schedule !!

DATES: Sep 25-28, 2025

CITY:Rapid City, SD

HOTEL: Best Western Ramkota Conference Hotel; 2111 North LaCrosse St., Rapid City, SD 57702; 605-343-8500

Click here to read about the reunion details.